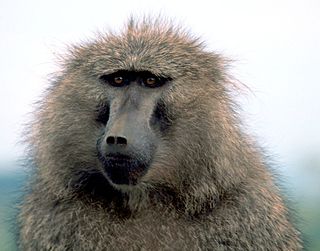

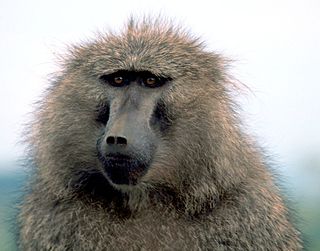

Primatology is the scientific study of primates. It is a diverse discipline at the boundary between mammalogy and anthropology, and researchers can be found in academic departments of anatomy, anthropology, biology, medicine, psychology, veterinary sciences and zoology, as well as in animal sanctuaries, biomedical research facilities, museums and zoos. Primatologists study both living and extinct primates in their natural habitats and in laboratories by conducting field studies and experiments in order to understand aspects of their evolution and behavior.

Proxemics is the study of human use of space and the effects that population density has on behavior, communication, and social interaction.

A hug is a form of endearment, found in virtually all human communities, in which two or more people put their arms around the neck, back, or waist of one another and hold each other closely. If more than two people are involved, it may be referred to as a group hug.

Body language is a type of communication in which physical behaviors, as opposed to words, are used to express or convey information. Such behavior includes facial expressions, body posture, gestures, eye movement, touch and the use of space. The term body language is usually applied in regard to people but may also be applied to animals. The study of body language is also known as kinesics. Although body language is an important part of communication, most of it happens without conscious awareness.

Public displays of affection (PDA) are acts of physical intimacy in the view of others. What is considered to be an acceptable display of affection varies with respect to culture and context.

Harry Frederick Harlow was an American psychologist best known for his maternal-separation, dependency needs, and social isolation experiments on rhesus monkeys, which manifested the importance of caregiving and companionship to social and cognitive development. He conducted most of his research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow worked with him for a short period of time.

Haptic communication is a branch of nonverbal communication that refers to the ways in which people and animals communicate and interact via the sense of touch. Touch is the most sophisticated and intimate of the five senses. Touch or haptics, from the ancient Greek word haptikos is extremely important for communication; it is vital for survival.

An intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves emotional or physical closeness between people and may include sexual intimacy and feelings of romance or love. Intimate relationships are interdependent, and the members of the relationship mutually influence each other. The quality and nature of the relationship depends on the interactions between individuals, and is derived from the unique context and history that builds between people over time. Social and legal institutions such as marriage acknowledge and uphold intimate relationships between people. However, intimate relationships are not necessarily monogamous or sexual, and there is wide social and cultural variability in the norms and practices of intimacy between people.

Social grooming is a behavior in which social animals, including humans, clean or maintain one another's bodies or appearances. A related term, allogrooming, indicates social grooming between members of the same species. Grooming is a major social activity and a means by which animals who live in close proximity may bond, reinforce social structures and family links, and build companionship. Social grooming is also used as a means of conflict resolution, maternal behavior, and reconciliation in some species. Mutual grooming typically describes the act of grooming between two individuals, often as a part of social grooming, pair bonding, or a precoital activity.

Dunbar's number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships—relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person.

Dependency need is "the vital, originally infantile needs for mothering, love, affection, shelter, protection, security, food, and warmth."

Human bonding is the process of development of a close interpersonal relationship between two or more people. It most commonly takes place between family members or friends, but can also develop among groups, such as sporting teams and whenever people spend time together. Bonding is a mutual, interactive process, and is different from simple liking. It is the process of nurturing social connection.

In psychology, the theory of attachment can be applied to adult relationships including friendships, emotional affairs, adult romantic and carnal relationships and, in some cases, relationships with inanimate objects. Attachment theory, initially studied in the 1960s and 1970s primarily in the context of children and parents, was extended to adult relationships in the late 1980s. The working models of children found in Bowlby's attachment theory form a pattern of interaction that is likely to continue influencing adult relationships.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to interpersonal relationships.

Social connection is the experience of feeling close and connected to others. It involves feeling loved, cared for, and valued, and forms the basis of interpersonal relationships.

"Connection is the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard and valued; when they can give and receive without judgement; and when they derive sustenance and strength from the relationship." —Brené Brown, Professor of social work at the University of Houston

Cognitive valence theory (CVT) is a theoretical framework that describes and explains the process of intimacy exchange within a dyad relationship. Peter A. Andersen, PhD created the cognitive valence theory to answer questions regarding intimacy relationships among colleagues, close friends and intimate friends, married couples and family members. Intimacy or immediacy behavior is that behavior that provides closeness or distance within a dyad relationship. Closeness projects a positive feeling in a relationship, and distance projects a negative feeling within a relationship. Intimacy or immediacy behavior can be negatively valenced or positively valenced. Valence, associated with physics, is used here to describe the degree of negativity or positivity in expected information. If your partner perceives your actions as negative, then the interaction may repel your partner away from you. If your partner perceives your actions as positive, then the interaction may be accepted and may encourage closeness. Affection and intimacy promotes positive valence in a relationship. CVT uses non-verbal and verbal communications criteria to analyze behavioral situations.

Animal non-reproductive sexual behavior encompasses sexual activities that non-human animals participate in which do not lead to the reproduction of the species. Although procreation continues to be the primary explanation for sexual behavior in animals, recent observations on animal behavior have given alternative reasons for the engagement in sexual activities by animals. Animals have been observed to engage in sex for social interaction bonding, exchange for significant materials, affection, mentorship pairings, sexual enjoyment, or as demonstration of social rank. Observed non-procreative sexual activities include non-copulatory mounting, oral sex, genital stimulation, anal stimulation, interspecies mating, and acts of affection, although it is doubted that they have done this since the beginning of their existence. There have also been observations of sex with cub participants, same-sex sexual interaction, as well as sex with dead animals.

Affiliative conflict theory (ACT) is a social psychological approach that encompasses interpersonal communication and has a background in nonverbal communication. This theory postulates that "people have competing needs or desires for intimacy and autonomy". In any relationship, people will negotiate and try to rationalize why they are acting the way they are in order to maintain a comfortable level of intimacy.

Tie signs are signs, signals, and symbols, that are revealed through people's actions as well as objects such as engagement rings, wedding bands, and photographs of a personal nature that suggest a relationship exists between two people. For romantic couples, public displays of affection (PDA) including things like holding hands, an arm around a partner's shoulders or waist, extended periods of physical contact, greater-than-normal levels of physical proximity, grooming one's partner, and “sweet talk” are all examples of common tie signs. Tie signs inform the participants, as well as outsiders, about the nature of a relationship, its condition, and even what stage a relationship is in.

Consoling touch is a pro-social behavior involving physical contact between a distressed individual and a caregiver. The physical contact, most commonly recognized in the form of a hand hold or embrace, is intended to comfort one or more of the participating individuals. Consoling touch is intended to provide consolation - to alleviate or lessen emotional or physical pain. This type of social support has been observed across species and cultures. Studies have found little difference in the applications of consoling touch, with minor differences in frequency occurrence across cultures. These findings suggest a degree of universality. It remains unclear whether the relationship between social touch and interpersonal emotional bonds reflect biologically driven or culturally normative behavior. Evidence of consoling touch in non-human primates, who embrace one another following distressing events, suggest a biological basis. Numerous studies of consoling touch in humans and animals unveil a consistent physiological response. An embrace from a friend, relative, or even stranger can trigger the release of oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin into the bloodstream. These neurotransmitters are associated with positive mood, numerous health benefits, and longevity. Cortisol, a stress hormone, also decreases. Studies have found that the degree of intimacy and quality of relationship between consoler and the consoled mediates physiological effects. In other words, while subjects experience reduced cortisol levels while holding the hand of a stranger, they exhibit a larger effect when receiving comfort from a trusted friend, and greater still, when holding the hand of a high quality romantic partner.