A pheromone is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavior of the receiving individuals. There are alarm pheromones, food trail pheromones, sex pheromones, and many others that affect behavior or physiology. Pheromones are used by many organisms, from basic unicellular prokaryotes to complex multicellular eukaryotes. Their use among insects has been particularly well documented. In addition, some vertebrates, plants and ciliates communicate by using pheromones. The ecological functions and evolution of pheromones are a major topic of research in the field of chemical ecology.

Ovulation is the release of eggs from the ovaries. In women, this event occurs when the ovarian follicles rupture and release the secondary oocyte ovarian cells. After ovulation, during the luteal phase, the egg will be available to be fertilized by sperm. In addition, the uterine lining (endometrium) is thickened to be able to receive a fertilized egg. If no conception occurs, the uterine lining as well as the egg will be shed during menstruation.

Concealed ovulation or hidden estrus in a species is the lack of any perceptible change in an adult female when she is fertile and near ovulation. Some examples of perceptible changes are swelling and redness of the vulva in baboons and bonobos, and pheromone release in the feline family. In contrast, the females of humans and a few other species that undergo hidden estrus have few external signs of fecundity, making it difficult for a mate to consciously deduce, by means of external signs only, whether or not a female is near ovulation.

Physical attractiveness is the degree to which a person's physical features are considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful. The term often implies sexual attractiveness or desirability, but can also be distinct from either. There are many factors which influence one person's attraction to another, with physical aspects being one of them. Physical attraction itself includes universal perceptions common to all human cultures such as facial symmetry, sociocultural dependent attributes and personal preferences unique to a particular individual.

A psychological adaptation is a functional, cognitive or behavioral trait that benefits an organism in its environment. Psychological adaptations fall under the scope of evolved psychological mechanisms (EPMs), however, EPMs refer to a less restricted set. Psychological adaptations include only the functional traits that increase the fitness of an organism, while EPMs refer to any psychological mechanism that developed through the processes of evolution. These additional EPMs are the by-product traits of a species’ evolutionary development, as well as the vestigial traits that no longer benefit the species’ fitness. It can be difficult to tell whether a trait is vestigial or not, so some literature is more lenient and refers to vestigial traits as adaptations, even though they may no longer have adaptive functionality. For example, xenophobic attitudes and behaviors, some have claimed, appear to have certain EPM influences relating to disease aversion, however, in many environments these behaviors will have a detrimental effect on a person's fitness. The principles of psychological adaptation rely on Darwin's theory of evolution and are important to the fields of evolutionary psychology, biology, and cognitive science.

Human male sexuality encompasses a wide variety of feelings and behaviors. Men's feelings of attraction may be caused by various physical and social traits of their potential partner. Men's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, including evolved predispositions, individual personality, upbringing, and culture. While most men are heterosexual, there are minorities of homosexual or varying degrees of bisexual men.

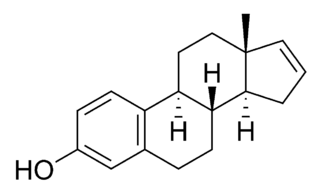

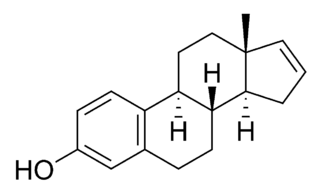

Estratetraenol, also known as estra-1,3,5(10),16-tetraen-3-ol, is an endogenous steroid found in women that has been described as having pheromone-like activities in primates, including humans. Estratetraenol is synthesized from androstadienone by aromatase likely in the ovaries, and is related to the estrogen sex hormones, yet has no known estrogenic effects. It was first identified from the urine of pregnant women.

Sexual selection in humans concerns the concept of sexual selection, introduced by Charles Darwin as an element of his theory of natural selection, as it affects humans. Sexual selection is a biological way one sex chooses a mate for the best reproductive success. Most compete with others of the same sex for the best mate to contribute their genome for future generations. This has shaped human evolution for many years, but reasons why humans choose their mates are not fully understood. Sexual selection is quite different in non-human animals than humans as they feel more of the evolutionary pressures to reproduce and can easily reject a mate. The role of sexual selection in human evolution has not been firmly established although neoteny has been cited as being caused by human sexual selection. It has been suggested that sexual selection played a part in the evolution of the anatomically modern human brain, i.e. the structures responsible for social intelligence underwent positive selection as a sexual ornamentation to be used in courtship rather than for survival itself, and that it has developed in ways outlined by Ronald Fisher in the Fisherian runaway model. Fisher also stated that the development of sexual selection was "more favourable" in humans.

An odor or odour is caused by one or more volatilized chemical compounds that are generally found in low concentrations that humans and many animals can perceive via their sense of smell. An odor is also called a "smell" or a "scent", which can refer to either an unpleasant or a pleasant odor.

Odour is sensory stimulation of the olfactory membrane of the nose by a group of molecules. Certain body odours are connected to human sexual attraction. Humans can make use of body odour subconsciously to identify whether a potential mate will pass on favourable traits to their offspring. Body odour may provide significant cues about the genetic quality, health and reproductive success of a potential mate.

Menstruation is the shedding of the uterine lining (endometrium). It occurs on a regular basis in uninseminated sexually reproductive-age females of certain mammal species.

Mate preferences in humans refers to why one human chooses or chooses not to mate with another human and their reasoning why. Men and women have been observed having different criteria as what makes a good or ideal mate. A potential mate's socioeconomic status has also been seen important, especially in developing areas where social status is more emphasized.

Sexual motivation is influenced by hormones such as testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability and motivation to engage in sexual behaviours.

Sexual swelling, sexual skin, or anogenital tumescence refers to localized engorgement of the anus and vulva region of some female primates that vary in size over the course of the menstrual cycle. Thought to be an honest signal of fertility, male primates are attracted to these swellings; preferring, and competing for, females with the largest swellings.

In evolutionary psychology and behavioral ecology, human mating strategies are a set of behaviors used by individuals to select, attract, and retain mates. Mating strategies overlap with reproductive strategies, which encompass a broader set of behaviors involving the timing of reproduction and the trade-off between quantity and quality of offspring.

Extended female sexuality is where the female of a species mates despite being infertile. In most species, the female only engages in copulation when she is fertile. However, extended sexuality has been documented in Old World primates, pair bonded birds and some insects. Extended sexuality is most prominent in human females who exhibit no change in copulation rate across the ovarian cycle.

Female intrasexual competition is competition between women over a potential mate. Such competition might include self-promotion, derogation of other women, and direct and indirect aggression toward other women. Factors that influence female intrasexual competition include the genetic quality of available mates, hormone levels, and interpersonal dynamics.

Human mate guarding refers to behaviours employed by both males and females with the aim of maintaining reproductive opportunities and sexual access to a mate. It involves discouraging the current mate from abandoning the relationship whilst also warding off intrasexual rivals. It has been observed in many non-human animals, as well as humans. Sexual jealousy is a prime example of mate guarding behaviour. Both males and females use different strategies to retain a mate and there is evidence that suggests resistance to mate guarding also exists.

No study has led to the isolation of true human sex pheromones, though various researchers have investigated the possibility of their existence. Sex pheromones are chemical (olfactory) signals, pheromones, released by an organism to attract an individual, encourage it to mate with it, or perform some other function closely related with sexual reproduction. While humans are highly dependent upon visual cues, when in proximity, smells also play a role in sociosexual behaviors. An inherent difficulty in studying human pheromones is the need for cleanliness and odorlessness in human participants. Experiments have focused on three classes of putative human pheromones: axillary steroids, vaginal aliphatic acids, and stimulators of the vomeronasal organ.

The ovulatory shift hypothesis holds that women experience evolutionarily adaptive changes in subconscious thoughts and behaviors related to mating during different parts of the ovulatory cycle. It suggests that what women want, in terms of men, changes throughout the menstrual cycle. Two meta-analyses published in 2014 reached opposing conclusions on whether the existing evidence was robust enough to support the prediction that women's mate preferences change across the cycle. A newer 2018 review does not show women changing the type of men they desire at different times in their fertility cycle.