Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Baddeley's model of working memory is a model of human memory proposed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974, in an attempt to present a more accurate model of primary memory. Working memory splits primary memory into multiple components, rather than considering it to be a single, unified construct.

Sex differences in psychology are differences in the mental functions and behaviors of the sexes and are due to a complex interplay of biological, developmental, and cultural factors. Differences have been found in a variety of fields such as mental health, cognitive abilities, personality, emotion, sexuality, friendship, and tendency towards aggression. Such variation may be innate, learned, or both. Modern research attempts to distinguish between these causes and to analyze any ethical concerns raised. Since behavior is a result of interactions between nature and nurture, researchers are interested in investigating how biology and environment interact to produce such differences, although this is often not possible.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. More analysis produce more elaborate and stronger memory than lower levels of processing. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace. There are three levels of processing in this model. Structural processing, or visual, is when we remember only the physical quality of the word E.g how the word is spelled and how letters look. Phonemic processing includes remembering the word by the way it sounds. E.G the word tall rhymes with fall. Lastly, we have semantic processing in which we encode the meaning of the word with another word that is similar or has similar meaning. Once the word is perceived, the brain allows for a deeper processing.

Mental rotation is the ability to rotate mental representations of two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects as it is related to the visual representation of such rotation within the human mind. There is a relationship between areas of the brain associated with perception and mental rotation. There could also be a relationship between the cognitive rate of spatial processing, general intelligence and mental rotation.

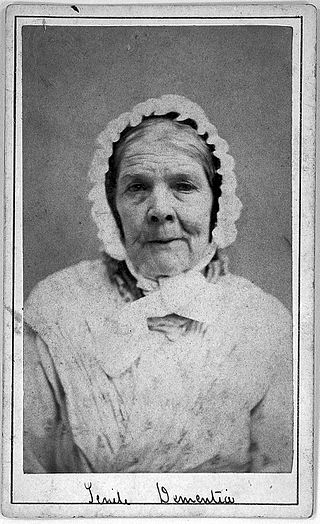

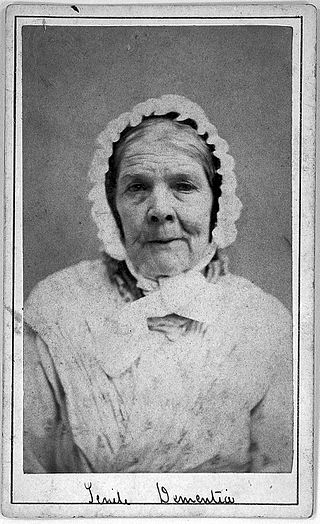

Age-related memory loss, sometimes described as "normal aging", is qualitatively different from memory loss associated with types of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, and is believed to have a different brain mechanism.

Spatial visualization ability or visual-spatial ability is the ability to mentally manipulate 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional figures. It is typically measured with simple cognitive tests and is predictive of user performance with some kinds of user interfaces.

Mate choice is one of the primary mechanisms under which evolution can occur. It is characterized by a "selective response by animals to particular stimuli" which can be observed as behavior. In other words, before an animal engages with a potential mate, they first evaluate various aspects of that mate which are indicative of quality—such as the resources or phenotypes they have—and evaluate whether or not those particular trait(s) are somehow beneficial to them. The evaluation will then incur a response of some sort.

Ethanol is the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages. It is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid that acts as a central nervous system depressant. Ethanol can impair different types of memory.

Adaptive memory is the study of memory systems that have evolved to help retain survival- and fitness-related information, i.e., that are geared toward helping an organism enhance its reproductive fitness and chances of surviving. One key element of adaptive memory research is the notion that memory evolved to help survival by better retaining information that is fitness-relevant. One of the foundations of this method of studying memory is the relatively little adaptive value of a memory system that evolved merely to remember past events. Memory systems, it is argued, must use the past in some service of the present or the planning of the future. Another assumption under this model is that the evolved memory mechanisms are likely to be domain-specific, or sensitive to certain types of information.

Spatial cognition is the acquisition, organization, utilization, and revision of knowledge about spatial environments. It is most about how animals including humans behave within space and the knowledge they built around it, rather than space itself. These capabilities enable individuals to manage basic and high-level cognitive tasks in everyday life. Numerous disciplines work together to understand spatial cognition in different species, especially in humans. Thereby, spatial cognition studies also have helped to link cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Scientists in both fields work together to figure out what role spatial cognition plays in the brain as well as to determine the surrounding neurobiological infrastructure.

The neuroscience of sex differences is the study of characteristics that separate brains of different sexes. Psychological sex differences are thought by some to reflect the interaction of genes, hormones, and social learning on brain development throughout the lifespan. A 2021 meta-synthesis led by Lise Eliot found that sex accounted for 1% of the brain's structure or laterality, finding large group-level differences only in total brain volume. A subsequent 2021 led by Camille Michèle Williams contradicted Eliot's conclusions, finding that sex differences in total brain volume are not accounted for merely by sex differences in height and weight, and that once global brain size is taken into account, there remain numerous regional sex differences in both directions. A 2022 follow-up meta-analysis led by Alex DeCasien analyzed the studies from both Eliot and Williams, concluding that "the human brain shows highly reproducible sex differences in regional brain anatomy above and beyond sex differences in overall brain size" and that these differences are of a "small-moderate effect size" A review from 2006 and a meta-analysis from 2014 found that some evidence from brain morphology and function studies indicates that male and female brains cannot always be assumed to be identical from either a structural or functional perspective, and some brain structures are sexually dimorphic.

This relationship between autism and memory, specifically memory functions in relation to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), has been an ongoing topic of research. ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by social communication and interaction impairments, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. In this article, the word autism is used to refer to the whole range of conditions on the autism spectrum, which are not uncommon.

Although there are many physiological and psychological gender differences in humans, memory, in general, is fairly stable across the sexes. By studying the specific instances in which males and females demonstrate differences in memory, we are able to further understand the brain structures and functions associated with memory.

Sex differences in human intelligence have long been a topic of debate among researchers and scholars. It is now recognized that there are no significant sex differences in average IQ, though particular subtypes of intelligence vary somewhat between sexes.

Sense of direction is the ability to know one's location and perform wayfinding. It is related to cognitive maps, spatial awareness, and spatial cognition. Sense of direction can be impaired by brain damage, such as in the case of topographical disorientation.

Emotional intelligence (EI) involves using cognitive and emotional abilities to function in interpersonal relationships, social groups as well as manage one's emotional states. It consists of abilities such as social cognition, empathy and also reasoning about the emotions of others.

Spatial ability or visuo-spatial ability is the capacity to understand, reason, and remember the visual and spatial relations among objects or space.

The evolution of cognition is the process by which life on Earth has gone from organisms with little to no cognitive function to a greatly varying display of cognitive function that we see in organisms today. Animal cognition is largely studied by observing behavior, which makes studying extinct species difficult. The definition of cognition varies by discipline; psychologists tend define cognition by human behaviors, while ethologists have widely varying definitions. Ethological definitions of cognition range from only considering cognition in animals to be behaviors exhibited in humans, while others consider anything action involving a nervous system to be cognitive.

Spatial anxiety is a sense of anxiety an individual experiences while processing environmental information contained in one's geographical space, with the purpose of navigation and orientation through that space. Spatial anxiety is also linked to the feeling of stress regarding the anticipation of a spatial-content related performance task. Particular cases of spatial anxiety can result in a more severe form of distress, as in agoraphobia.