Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes with input from linguistics, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, computer science/artificial intelligence, and anthropology. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition. Cognitive scientists study intelligence and behavior, with a focus on how nervous systems represent, process, and transform information. Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include language, perception, memory, attention, reasoning, and emotion; to understand these faculties, cognitive scientists borrow from fields such as linguistics, psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, and anthropology. The typical analysis of cognitive science spans many levels of organization, from learning and decision to logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. One of the fundamental concepts of cognitive science is that "thinking can best be understood in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures."

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning.

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system, its functions and disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, developmental biology, cytology, psychology, physics, computer science, chemistry, medicine, statistics, and mathematical modeling to understand the fundamental and emergent properties of neurons, glia and neural circuits. The understanding of the biological basis of learning, memory, behavior, perception, and consciousness has been described by Eric Kandel as the "epic challenge" of the biological sciences.

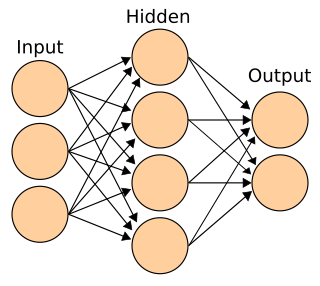

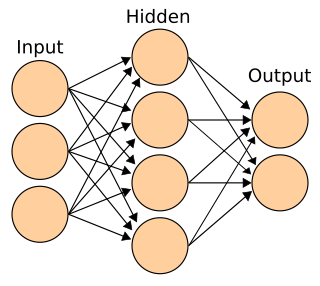

Connectionism is the name of an approach to the study of human mental processes and cognition that utilizes mathematical models known as connectionist networks or artificial neural networks. Connectionism has had many 'waves' since its beginnings.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to neuroscience:

Neuropsychology is a branch of psychology concerned with how a person's cognition and behavior are related to the brain and the rest of the nervous system. Professionals in this branch of psychology focus on how injuries or illnesses of the brain affect cognitive and behavioral functions.

A cognitive model is an approximation of one or more cognitive processes in humans or other animals for the purposes of comprehension and prediction. There are many types of cognitive models, and they can range from box-and-arrow diagrams to a set of equations to software programs that interact with the same tools that humans use to complete tasks. In terms of information processing, cognitive modeling is modeling of human perception, reasoning, memory and action.

Cognitive neuropsychology is a branch of cognitive psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes. Cognitive psychology is the science that looks at how mental processes are responsible for the cognitive abilities to store and produce new memories, produce language, recognize people and objects, as well as our ability to reason and problem solve. Cognitive neuropsychology places a particular emphasis on studying the cognitive effects of brain injury or neurological illness with a view to inferring models of normal cognitive functioning. Evidence is based on case studies of individual brain damaged patients who show deficits in brain areas and from patients who exhibit double dissociations. Double dissociations involve two patients and two tasks. One patient is impaired at one task but normal on the other, while the other patient is normal on the first task and impaired on the other. For example, patient A would be poor at reading printed words while still being normal at understanding spoken words, while the patient B would be normal at understanding written words and be poor at understanding spoken words. Scientists can interpret this information to explain how there is a single cognitive module for word comprehension. From studies like these, researchers infer that different areas of the brain are highly specialised. Cognitive neuropsychology can be distinguished from cognitive neuroscience, which is also interested in brain-damaged patients, but is particularly focused on uncovering the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive processes.

Behavioral neuroscience, also known as biological psychology, biopsychology, or psychobiology, is the application of the principles of biology to the study of physiological, genetic, and developmental mechanisms of behavior in humans and other animals.

The cognitive revolution was an intellectual movement that began in the 1950s as an interdisciplinary study of the mind and its processes, from which emerged a new field known as cognitive science. The preexisting relevant fields were psychology, linguistics, computer science, anthropology, neuroscience, and philosophy. The approaches used were developed within the then-nascent fields of artificial intelligence, computer science, and neuroscience. In the 1960s, the Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies and the Center for Human Information Processing at the University of California, San Diego were influential in developing the academic study of cognitive science. By the early 1970s, the cognitive movement had surpassed behaviorism as a psychological paradigm. Furthermore, by the early 1980s the cognitive approach had become the dominant line of research inquiry across most branches in the field of psychology.

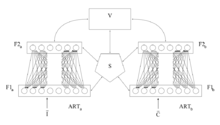

Stephen Grossberg is a cognitive scientist, theoretical and computational psychologist, neuroscientist, mathematician, biomedical engineer, and neuromorphic technologist. He is the Wang Professor of Cognitive and Neural Systems and a Professor Emeritus of Mathematics & Statistics, Psychological & Brain Sciences, and Biomedical Engineering at Boston University.

Neuroinformatics is the field that combines informatics and neuroscience. Neuroinformatics is related with neuroscience data and information processing by artificial neural networks. There are three main directions where neuroinformatics has to be applied:

Stanislas Dehaene is a French author and cognitive neuroscientist whose research centers on a number of topics, including numerical cognition, the neural basis of reading and the neural correlates of consciousness. As of 2017, he is a professor at the Collège de France and, since 1989, the director of INSERM Unit 562, "Cognitive Neuroimaging".

Some of the research that is conducted in the field of psychology is more "fundamental" than the research conducted in the applied psychological disciplines, and does not necessarily have a direct application. The subdisciplines within psychology that can be thought to reflect a basic-science orientation include biological psychology, cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and so on. Research in these subdisciplines is characterized by methodological rigor. The concern of psychology as a basic science is in understanding the laws and processes that underlie behavior, cognition, and emotion. Psychology as a basic science provides a foundation for applied psychology. Applied psychology, by contrast, involves the application of psychological principles and theories yielded up by the basic psychological sciences; these applications are aimed at overcoming problems or promoting well-being in areas such as mental and physical health and education.

Cultural neuroscience is a field of research that focuses on the interrelation between a human's cultural environment and neurobiological systems. The field particularly incorporates ideas and perspectives from related domains like anthropology, psychology, and cognitive neuroscience to study sociocultural influences on human behaviors. Such impacts on behavior are often measured using various neuroimaging methods, through which cross-cultural variability in neural activity can be examined.

Malleability of intelligence describes the processes by which intelligence can increase or decrease over time and is not static. These changes may come as a result of genetics, pharmacological factors, psychological factors, behavior, or environmental conditions. Malleable intelligence may refer to changes in cognitive skills, memory, reasoning, or muscle memory related motor skills. In general, the majority of changes in human intelligence occur at either the onset of development, during the critical period, or during old age.

The Troland Research Awards are an annual prize given by the United States National Academy of Sciences to two researchers in recognition of psychological research on the relationship between consciousness and the physical world. The areas where these award funds are to be spent include but are not limited to areas of experimental psychology, the topics of sensation, perception, motivation, emotion, learning, memory, cognition, language, and action. The award preference is given to experimental work with a quantitative approach or experimental research seeking physiological explanations.

Mark A. Gluck is a professor of neuroscience at Rutgers–Newark in New Jersey, director of the Rutgers Memory Disorders Project, and publisher of the public health newsletter, Memory Loss and the Brain. He works at the interface between neuroscience, psychology, and computer science, studying the neural bases of learning and memory. He is the co-author of Gateway to Memory: An Introduction to Neural Network Models of the Hippocampus and an undergraduate textbook Learning and Memory: From Brain to Behavior.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the human brain:

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.