Related Research Articles

Arachnophobia is the fear of spiders and other arachnids such as scorpions and ticks. The word Arachnophobia comes from the Greek words arachne and phobia.

A mental disorder is an impairment of the mind disrupting normal thinking, feeling, mood, behavior, or social interactions, and accompanied by significant distress or dysfunction. The causes of mental disorders are very complex and vary depending on the particular disorder and the individual. Although the causes of most mental disorders are not fully understood, researchers have identified a variety of biological, psychological, and environmental factors that can contribute to the development or progression of mental disorders. Most mental disorders result in a combination of several different factors rather than just a single factor.

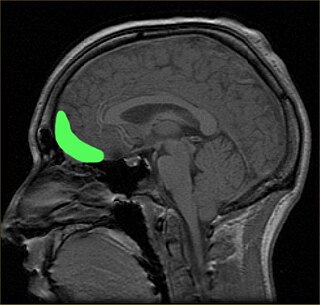

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate.

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a personality disorder characterized by a life-long pattern of exaggerated feelings of self-importance, an excessive need for admiration, and a diminished ability to empathize with other people's feelings. Narcissistic personality disorder is one of the sub-types of the broader category known as personality disorders. It is often comorbid with other mental disorders and associated with significant functional impairment and psychosocial disability.

Anhedonia is a diverse array of deficits in hedonic function, including reduced motivation or ability to experience pleasure. While earlier definitions emphasized the inability to experience pleasure, anhedonia is currently used by researchers to refer to reduced motivation, reduced anticipatory pleasure (wanting), reduced consummatory pleasure (liking), and deficits in reinforcement learning. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), anhedonia is a component of depressive disorders, substance-related disorders, psychotic disorders, and personality disorders, where it is defined by either a reduced ability to experience pleasure, or a diminished interest in engaging in previously pleasurable activities. While the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) does not explicitly mention anhedonia, the depressive symptom analogous to anhedonia as described in the DSM-5 is a loss of interest or pleasure.

Avoidant personality disorder (AvPD) or Anxious personality disorder is a Cluster C personality disorder characterized by excessive social anxiety and inhibition, fear of intimacy, severe feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, and an overreliance on avoidance of feared stimuli as a maladaptive coping method. Those affected typically display a pattern of extreme sensitivity to negative evaluation and rejection, a belief that one is socially inept or personally unappealing to others, and avoidance of social interaction despite a strong desire for it. It appears to affect an approximately equal number of men and women.

The fight-or-flight or the fight-flight-freeze-or-fawn is a physiological reaction that occurs in response to a perceived harmful event, attack, or threat to survival. It was first described by Walter Bradford Cannon. His theory states that animals react to threats with a general discharge of the sympathetic nervous system, preparing the animal for fighting or fleeing. More specifically, the adrenal medulla produces a hormonal cascade that results in the secretion of catecholamines, especially norepinephrine and epinephrine. The hormones estrogen, testosterone, and cortisol, as well as the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin, also affect how organisms react to stress. The hormone osteocalcin might also play a part.

Criminal psychology, also referred to as criminological psychology, is the study of the views, thoughts, intentions, actions and reactions of criminals and suspects. It is a subfield of criminology and applied psychology.

Ophidiophobia is fear of snakes. It is sometimes called by the more general term herpetophobia, fear of reptiles. The word comes from the Greek words "ophis" (ὄφις), snake, and "phobia" (φοβία) meaning fear.

Hyperfocus is an intense form of mental concentration or visualization that focuses consciousness on a subject, topic, or task. In some individuals, various subjects or topics may also include daydreams, concepts, fiction, the imagination, and other objects of the mind. Hyperfocus on a certain subject can cause side-tracking away from assigned or important tasks.

Cognitive disengagement syndrome (CDS) is an attention syndrome characterised by prominent dreaminess, mental fogginess, hypoactivity, sluggishness, slow reaction time, staring frequently, inconsistent alertness, and a slow working speed. To scientists in the field, it has reached the threshold of evidence and recognition as a distinct syndrome.

Randolph Martin Nesse is an American physician, scientist and author who is notable for his role as a founder of the field of evolutionary medicine and evolutionary psychiatry.

Psychopathy, or psychopathic personality is a personality construct characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, and bold, disinhibited, and egocentric traits masked by superficial charm and the outward presence of apparent normality.

Evolutionary approaches to depression are attempts by evolutionary psychologists to use the theory of evolution to shed light on the problem of mood disorders within the perspective of evolutionary psychiatry. Depression is generally thought of as dysfunction or a mental disorder, but its prevalence does not increase with age the way dementia and other organic dysfunction commonly does. Some researchers have surmised that the disorder may have evolutionary roots, in the same way that others suggest evolutionary contributions to schizophrenia, sickle cell anemia, psychopathy and other disorders. Psychology and psychiatry have not generally embraced evolutionary explanations for behaviors, and the proposed explanations for the evolution of depression remain controversial.

In psychology, impulsivity is a tendency to act on a whim, displaying behavior characterized by little or no forethought, reflection, or consideration of the consequences. Impulsive actions are typically "poorly conceived, prematurely expressed, unduly risky, or inappropriate to the situation that often result in undesirable consequences," which imperil long-term goals and strategies for success. Impulsivity can be classified as a multifactorial construct. A functional variety of impulsivity has also been suggested, which involves action without much forethought in appropriate situations that can and does result in desirable consequences. "When such actions have positive outcomes, they tend not to be seen as signs of impulsivity, but as indicators of boldness, quickness, spontaneity, courageousness, or unconventionality." Thus, the construct of impulsivity includes at least two independent components: first, acting without an appropriate amount of deliberation, which may or may not be functional; and second, choosing short-term gains over long-term ones.

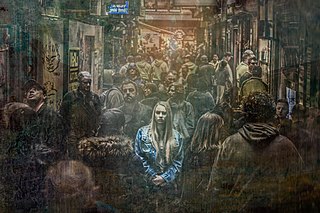

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), also known as social phobia, is an anxiety disorder characterized by sentiments of fear and anxiety in social situations, causing considerable distress and impairing ability to function in at least some aspects of daily life. These fears can be triggered by perceived or actual scrutiny from others. Individuals with social anxiety disorder fear negative evaluations from other people.

The fear of falling (FOF), also referred to as basophobia, is a natural fear and is typical of most humans and mammals, in varying degrees of extremity. It differs from acrophobia, although the two fears are closely related. The fear of falling encompasses the anxieties accompanying the sensation and the possibly dangerous effects of falling, as opposed to the heights themselves. Those who have little fear of falling may be said to have a head for heights. Basophobia is sometimes associated with astasia-abasia, the fear of walking/standing erect.

Evolutionary psychiatry, also known as Darwinian psychiatry, is a theoretical approach to psychiatry that aims to explain psychiatric disorders in evolutionary terms. As a branch of the field of evolutionary medicine, it is distinct from the medical practice of psychiatry in its emphasis on providing scientific explanations rather than treatments for mental disorder. This often concerns questions of ultimate causation. For example, psychiatric genetics may discover genes associated with mental disorders, but evolutionary psychiatry asks why those genes persist in the population. Other core questions in evolutionary psychiatry are why heritable mental disorders are so common how to distinguish mental function and dysfunction, and whether certain forms of suffering conveyed an adaptive advantage. Disorders commonly considered are depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, autism, eating disorders, and others. Key explanatory concepts are of evolutionary mismatch and the fact that evolution is guided by reproductive success rather than health or wellbeing. Rather than providing an alternative account of the cause of mental disorder, evolutionary psychiatry seeks to integrate findings from traditional schools of psychology and psychiatry such as social psychology, behaviourism, biological psychiatry and psychoanalysis into a holistic account related to evolutionary biology. In this sense, it aims to meet the criteria of a Kuhnian paradigm shift.

Social selection is a term used with varying meanings in biology.

The relationships between digital media use and mental health have been investigated by various researchers—predominantly psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and medical experts—especially since the mid-1990s, after the growth of the World Wide Web. A significant body of research has explored "overuse" phenomena, commonly known as "digital addictions", or "digital dependencies." These phenomena manifest differently in many societies and cultures. Some experts have investigated the benefits of moderate digital media use in various domains, including in mental health, and the treatment of mental health problems with novel technological solutions.

References

- ↑ "Insider information: How insurance companies measure risk". Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ Greenwood, M. and Woods, H.M. (1919) The incidence of industrial accidents upon individuals with special reference to multiple accidents. Industrial Fatigue Research Board, Medical Research Committee, Report No. 4. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London.

- ↑ "創造性テスト、薬不要の風邪治療(妊婦、アスリート、NSAID)、適性テスト". F6.dion.ne.jp. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1955 (PDF) (Report). Statistical Abstract of the United States (76 ed.). U.S. Census Bureau. 1955. p. 554. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 217. ISBN 978-0684832838.

- ↑ File, Thom (May 2013). Computer and Internet Use in the United States (PDF) (Report). Current Population Survey Reports. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ↑ Tuckel, Peter; O'Neill, Harry (2005). Ownership and Usage Patterns of Cell Phones: 2000–2005 (PDF) (Report). JSM Proceedings, Survey Research Methods Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association. p. 4002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ "Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States". Pew Research Center. 7 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ↑ Dugatkin, Lee Alan (1992). "Tendency to inspect predators predicts mortality risk in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata)". Behavioral Ecology . 3 (2). Oxford University Press: 125–127. doi:10.1093/beheco/3.2.124 . Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph; Williams, George C. (1994). Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine. New York: Vintage Books. p. 213. ISBN 978-0679746744.

- ↑ Öhman, Arne (1993). "Fear and anxiety as emotional phenomena: Clinical phenomenology, evolutionary perspectives, and information-processing mechanisms". In Lewis, Michael; Haviland, Jeannette M. (eds.). The Handbook of the Emotions (1st ed.). New York: Guilford Press. pp. 511–536. ISBN 978-0898629880.

- ↑ Mineka, Susan; Keir, Richard; Price, Veda (1980). "Fear of snakes in wild- and laboratory-reared rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta)" (PDF). Animal Learning & Behavior . 8 (4). Springer Science+Business Media: 653–663. doi: 10.3758/BF03197783 . S2CID 144602361.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (2009) [1872]. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. New York: Penguin Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-0141439440.

- ↑ Ekman, Paul (2007) [2003]. Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life (Revised ed.). New York: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0805083392.

- ↑ Poulton, Richie; Davies, Simon; Menzies, Ross G.; Langley, John D.; Silva, Phil A. (1998). "Evidence for a non-associative model of the acquisition of a fear of heights". Behaviour Research and Therapy . 36 (5). Elsevier: 537–544. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10037-7. PMID 9648329.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph; Williams, George C. (1994). Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-0679746744.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph M. (2005). "32. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss, David M. (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (1st ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 911–913. ISBN 978-0471264033.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph M. (2016) [2005]. "43. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss, David M. (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 2: Integrations (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 1014. ISBN 978-1118755808.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph (2019). Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry. Dutton. pp. 64–76. ISBN 978-1101985663.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph (2019). Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry. Dutton. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1101985663.

- ↑ Brook, Uzi; Boaz, Mona (2006). "Adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder/learning disability and their proneness to accidents". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 73 (4). Dr. K.C. Chaudhuri Foundation: 299–303. doi:10.1007/BF02825823. PMID 16816490. S2CID 956356.

- ↑ Lange, Hannah; Buse, Judith; Bender, Stephan; Siegert, Joachim; Knopf, Hildtraud; Roessner, Veit (2016). "Accident Proneness in Children and Adolescents Affected by ADHD and the Impact of Medication". Journal of Attention Disorders . 20 (6). SAGE Publications: 501–509. doi:10.1177/1087054713518237. PMID 24470540. S2CID 38278653.

- ↑ Turel, Ofir; Bechara, Antoine (2016). "Social Networking Site Use While Driving: ADHD and the Mediating Roles of Stress, Self-Esteem and Craving". Frontiers in Psychology . 7: 455. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00455 . PMC 4812103 . PMID 27065923.

- ↑ Vaa, Truls (2014). "ADHD and relative risk of accidents in road traffic: A meta-analysis". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 62. Elsevier: 415–425. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.003. hdl: 11250/2603537 . PMID 24238842.

- ↑ Brunkhorst-Kanaan, Nathalie; Libutzki, Berit; Reif, Andreas; Larsson, Henrik; McNeill, Rhiannon V.; Kittel-Schneider, Sarah (2021). "ADHD and accidents over the life span – A systematic review". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 125. Elsevier: 582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.02.002 . PMID 33582234.

- ↑ Biederman, Joseph; Spencer, Thomas (1999). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (adhd) as a noradrenergic disorder". Biological Psychiatry . 46 (9). Elsevier: 1234–1242. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00192-4. PMID 10560028. S2CID 45497168. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ Faraone, Stephen V.; Larsson, Henrik (2019). "Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Molecular Psychiatry . 24 (4). Nature Research: 562–575. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. PMC 6477889 . PMID 29892054.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen, Simon (2002). "The extreme male brain theory of autism". Trends in Cognitive Sciences . 6 (6). Elsevier: 248–254. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01904-6. PMID 12039606. S2CID 8098723. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph M. (2005). "32. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss, David M. (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (1st ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 918. ISBN 978-0471264033.

- ↑ Nesse, Randolph M. (2016) [2005]. "43. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health". In Buss, David M. (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 2: Integrations (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 1019. ISBN 978-1118755808.

- ↑ McAdams DP (1995). "What do we know when we know a person?". Journal of Personality. 63 (3): 365–96. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.6832 . doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00500.x.

- ↑ Haidt, Jonathan (2006). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. New York: Basic Books. pp. 141–145. ISBN 978-0465028023.

- ↑ Block J (2010). "The five-factor framing of personality and beyond: Some ruminations". Psychological Inquiry. 21 (1): 2–25. doi:10.1080/10478401003596626. S2CID 26355524.

- ↑ Epstein S, O'Brien EJ (November 1985). "The person-situation debate in historical and current perspective". Psychological Bulletin. 98 (3): 513–37. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.3.513. PMID 4080897.

- ↑ Kenrick DT, Funder DC (January 1988). "Profiting from controversy. Lessons from the person-situation debate". The American Psychologist. 43 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.43.1.23. PMID 3279875.

- ↑ Costa PT, McCrae RR (1992). "Reply to Eysenck". Personality and Individual Differences. 13 (8): 861–65. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90002-7.

- ↑ Costa PT, McCrae RR (1995). "Solid ground in the wetlands of personality: A reply to Block". Psychological Bulletin. 117 (2): 216–20. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.216. PMID 7724688.

- ↑ Baumeister, Roy (September 2016). "Charting the future of social psychology on stormy seas: Winners, losers, and recommendations". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology . 66: 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.003.

- ↑ "The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R)". The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment. 2: 223–257 – via Researchgate.

- ↑ Goldberg, Lewis R.; Johnson, John A.; Eber, Herbert W.; Hogan, Robert; Ashton, Michael C.; Cloninger, C. Robert; Gough, Harrison G. (2006). "The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures" (PDF). Journal of Research in Personality. 40: 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007. S2CID 13274640 – via Elsevier.

- ↑ Deyoung, C. G.; Quilty, L. C.; Peterson, J. B. (2007). "Between Facets and Domains: 10 Aspects of the Big Five". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 93 (5): 880–896. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.513.2517 . doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880. PMID 17983306. S2CID 8261816.

Bundled references