Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning.

Educational psychology is the branch of psychology concerned with the scientific study of human learning. The study of learning processes, from both cognitive and behavioral perspectives, allows researchers to understand individual differences in intelligence, cognitive development, affect, motivation, self-regulation, and self-concept, as well as their role in learning. The field of educational psychology relies heavily on quantitative methods, including testing and measurement, to enhance educational activities related to instructional design, classroom management, and assessment, which serve to facilitate learning processes in various educational settings across the lifespan.

Jean William Fritz Piaget was a Swiss psychologist known for his work on child development. Piaget's theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology".

Human intelligence is the intellectual capability of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness. Using their intelligence, humans are able to learn, form concepts, understand, and apply logic and reason. Human intelligence is also thought to encompass our capacities to recognize patterns, plan, innovate, solve problems, make decisions, retain information, and use language to communicate.

In cognitive psychology, information processing is an approach to the goal of understanding human thinking that treats cognition as essentially computational in nature, with the mind being the software and the brain being the hardware. It arose in the 1940s and 1950s, after World War II. The information processing approach in psychology is closely allied to the computational theory of mind in philosophy; it is also related to cognitivism in psychology and functionalism in philosophy.

Modularity of mind is the notion that a mind may, at least in part, be composed of innate neural structures or mental modules which have distinct, established, and evolutionarily developed functions. However, different definitions of "module" have been proposed by different authors. According to Jerry Fodor, the author of Modularity of Mind, a system can be considered 'modular' if its functions are made of multiple dimensions or units to some degree. One example of modularity in the mind is binding. When one perceives an object, they take in not only the features of an object, but the integrated features that can operate in sync or independently that create a whole. Instead of just seeing red, round, plastic, and moving, the subject may experience a rolling red ball. Binding may suggest that the mind is modular because it takes multiple cognitive processes to perceive one thing.

The concepts of fluid intelligence (gf) and crystallized intelligence (gc) were introduced in 1963 by the psychologist Raymond Cattell. According to Cattell's psychometrically-based theory, general intelligence (g) is subdivided into gf and gc. Fluid intelligence is the ability to solve novel reasoning problems and is correlated with a number of important skills such as comprehension, problem-solving, and learning. Crystallized intelligence, on the other hand, involves the ability to deduce secondary relational abstractions by applying previously learned primary relational abstractions.

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development, or his "genetic epistemology," is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence. It was originated by the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). The theory deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans gradually come to acquire, construct, and use it. Piaget's theory is mainly known as a developmental stage theory.

Cognitive development is a field of study in neuroscience and psychology focusing on a child's development in terms of information processing, conceptual resources, perceptual skill, language learning, and other aspects of the developed adult brain and cognitive psychology. Qualitative differences between how a child processes their waking experience and how an adult processes their waking experience are acknowledged. Cognitive development is defined as the emergence of the ability to consciously cognize, understand, and articulate their understanding in adult terms. Cognitive development is how a person perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of their world through the relations of genetic and learning factors. There are four stages to cognitive information development. They are, reasoning, intelligence, language, and memory. These stages start when the baby is about 18 months old, they play with toys, listen to their parents speak, they watch TV, anything that catches their attention helps build their cognitive development.

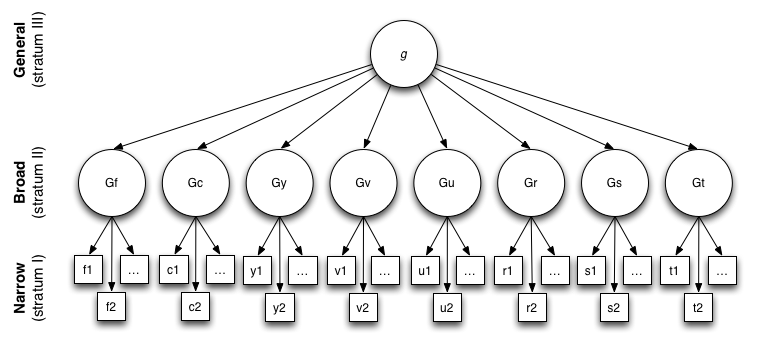

The three-stratum theory is a theory of cognitive ability proposed by the American psychologist John Carroll in 1993. It is based on a factor-analytic study of the correlation of individual-difference variables from data such as psychological tests, school marks and competence ratings from more than 460 datasets. These analyses suggested a three-layered model where each layer accounts for the variations in the correlations within the previous layer.

Evolutionary educational psychology is the study of the relation between inherent folk knowledge and abilities and accompanying inferential and attributional biases as these influence academic learning in evolutionarily novel cultural contexts, such as schools and the industrial workplace. The fundamental premises and principles of this discipline are presented below.

Neuroconstructivism is a theory that states that phylogenetic developmental processes such as gene–gene interaction, gene–environment interaction and, crucially, ontogeny all play a vital role in how the brain progressively sculpts itself and how it gradually becomes specialized over developmental time.

The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory, is a psychological theory on the structure of human cognitive abilities. Based on the work of three psychologists, Raymond B. Cattell, John L. Horn and John B. Carroll, the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory is regarded as an important theory in the study of human intelligence. Based on a large body of research, spanning over 70 years, Carroll's Three Stratum theory was developed using the psychometric approach, the objective measurement of individual differences in abilities, and the application of factor analysis, a statistical technique which uncovers relationships between variables and the underlying structure of concepts such as 'intelligence'. The psychometric approach has consistently facilitated the development of reliable and valid measurement tools and continues to dominate the field of intelligence research.

Domain-specific learning theories of development hold that we have many independent, specialised knowledge structures (domains), rather than one cohesive knowledge structure. Thus, training in one domain may not impact another independent domain. Domain-general views instead suggest that children possess a "general developmental function" where skills are interrelated through a single cognitive system. Therefore, whereas domain-general theories would propose that acquisition of language and mathematical skill are developed by the same broad set of cognitive skills, domain-specific theories would propose that they are genetically, neurologically and computationally independent.

Neurodevelopmental framework for learning, like all frameworks, is an organizing structure through which learners and learning can be understood. Intelligence theories and neuropsychology inform many of them. The framework described below is a neurodevelopmental framework for learning. The neurodevelopmental framework was developed by the All Kinds of Minds Institute in collaboration with Dr. Mel Levine and the University of North Carolina's Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning. It is similar to other neuropsychological frameworks, including Alexander Luria's cultural-historical psychology and psychological activity theory, but also draws from disciplines such as speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, and physical therapy. It also shares components with other frameworks, some of which are listed below. However, it does not include a general intelligence factor, since the framework is used to describe learners in terms of profiles of strengths and weaknesses, as opposed to using labels, diagnoses, or broad ability levels. This framework was also developed to link with academic skills, such as reading and writing. Implications for education are discussed below as well as the connections to and compatibilities with several major educational policy issues.

Neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development criticize and build upon Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development.

Andreas Demetriou is a Greek Cypriot developmental psychologist and former Minister of Education and Culture of Cyprus. He is a founding fellow and president of The Cyprus Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts.

Educational neuroscience is an emerging scientific field that brings together researchers in cognitive neuroscience, developmental cognitive neuroscience, educational psychology, educational technology, education theory and other related disciplines to explore the interactions between biological processes and education. Researchers in educational neuroscience investigate the neural mechanisms of reading, numerical cognition, attention and their attendant difficulties including dyslexia, dyscalculia and ADHD as they relate to education. Researchers in this area may link basic findings in cognitive neuroscience with educational technology to help in curriculum implementation for mathematics education and reading education. The aim of educational neuroscience is to generate basic and applied research that will provide a new transdisciplinary account of learning and teaching, which is capable of informing education. A major goal of educational neuroscience is to bridge the gap between the two fields through a direct dialogue between researchers and educators, avoiding the "middlemen of the brain-based learning industry". These middlemen have a vested commercial interest in the selling of "neuromyths" and their supposed remedies.

Childhood memory refers to memories formed during childhood. Among its other roles, memory functions to guide present behaviour and to predict future outcomes. Memory in childhood is qualitatively and quantitatively different from the memories formed and retrieved in late adolescence and the adult years. Childhood memory research is relatively recent in relation to the study of other types of cognitive processes underpinning behaviour. Understanding the mechanisms by which memories in childhood are encoded and later retrieved has important implications in many areas. Research into childhood memory includes topics such as childhood memory formation and retrieval mechanisms in relation to those in adults, controversies surrounding infantile amnesia and the fact that adults have relatively poor memories of early childhood, the ways in which school environment and family environment influence memory, and the ways in which memory can be improved in childhood to improve overall cognition, performance in school, and well-being, both in childhood and in adulthood.

Juan Pascual-Leone is a developmental psychologist and founder of the neo-Piagetian approach to cognitive development. He introduced this term into the literature and put forward key predictions about developmental growth of mental attention and working memory.