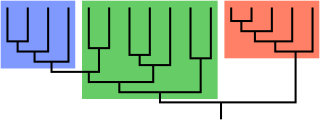

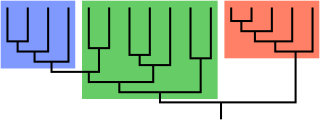

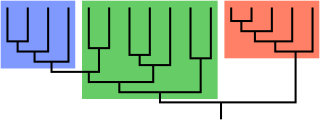

In biological phylogenetics, a clade, also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a grouping of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. In the taxonomical literature, sometimes the Latin form cladus is used rather than the English form. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach to taxonomy adopted by most biological fields.

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

- The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his Systema Naturae (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus there are three kingdoms, divided into classes, and they, in turn, into lower ranks in a hierarchical order.

- A term for rank-based classification of organisms, in general. That is, taxonomy in the traditional sense of the word: rank-based scientific classification. This term is especially used as opposed to cladistic systematics, which groups organisms into clades. It is attributed to Linnaeus, although he neither invented the concept of ranked classification nor gave it its present form. In fact, it does not have an exact present form, as "Linnaean taxonomy" as such does not really exist: it is a collective (abstracting) term for what actually are several separate fields, which use similar approaches.

In biology, taxonomy is the scientific study of naming, defining (circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa and these groups are given a taxonomic rank; groups of a given rank can be aggregated to form a more inclusive group of higher rank, thus creating a taxonomic hierarchy. The principal ranks in modern use are domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus is regarded as the founder of the current system of taxonomy, as he developed a ranked system known as Linnaean taxonomy for categorizing organisms and binomial nomenclature for naming organisms.

Zoology is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one of the primary branches of biology. The term is derived from Ancient Greek ζῷον, zōion ('animal'), and λόγος, logos.

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature, also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, although they can be based on words from other languages. Such a name is called a binomial name, a binomen, binominal name, or a scientific name; more informally it is also historically called a Latin name. In the ICZN, the system is also called binominal nomenclature, "binomi'N'al" with an "N" before the "al", which is not a typographic error, meaning "two-name naming system".

Family is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between order and genus. A family may be divided into subfamilies, which are intermediate ranks between the ranks of family and genus. The official family names are Latin in origin; however, popular names are often used: for example, walnut trees and hickory trees belong to the family Juglandaceae, but that family is commonly referred to as the "walnut family".

Order is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized by the nomenclature codes. An immediately higher rank, superorder, is sometimes added directly above order, with suborder directly beneath order. An order can also be defined as a group of related families.

In biology, a taxon is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and given a particular ranking, especially if and when it is accepted or becomes established. It is very common, however, for taxonomists to remain at odds over what belongs to a taxon and the criteria used for inclusion, especially in the context of rank-based ("Linnaean") nomenclature. If a taxon is given a formal scientific name, its use is then governed by one of the nomenclature codes specifying which scientific name is correct for a particular grouping.

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often contrasted with the scientific name for the same organism, which is often based in Latin. A common name is sometimes frequently used, but that is not always the case.

Nomenclature is a system of names or terms, or the rules for forming these terms in a particular field of arts or sciences. The principles of naming vary from the relatively informal conventions of everyday speech to the internationally agreed principles, rules and recommendations that govern the formation and use of the specialist terminology used in scientific and any other disciplines.

Systema Naturae is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature, was partially developed by the Bauhin brothers, Gaspard and Johann, Linnaeus was first to use it consistently throughout his book. The first edition was published in 1735. The full title of the 10th edition (1758), which was the most important one, was Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis or translated: "System of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places".

Overton Brent Berlin is an American anthropologist, most noted for his work with linguist Paul Kay on color, and his ethnobiological research among the Maya of Chiapas, Mexico.

Botanical nomenclature is the formal, scientific naming of plants. It is related to, but distinct from taxonomy. Plant taxonomy is concerned with grouping and classifying plants; botanical nomenclature then provides names for the results of this process. The starting point for modern botanical nomenclature is Linnaeus' Species Plantarum of 1753. Botanical nomenclature is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), which replaces the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN). Fossil plants are also covered by the code of nomenclature.

Nomenclature codes or codes of nomenclature are the various rulebooks that govern biological taxonomic nomenclature, each in their own broad field of organisms. To an end-user who only deals with names of species, with some awareness that species are assignable to genera, families, and other taxa of higher ranks, it may not be noticeable that there is more than one code, but beyond this basic level these are rather different in the way they work.

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional approach, in which taxon names are defined by a type, which can be a specimen or a taxon of lower rank, and a description in words. Phylogenetic nomenclature is currently regulated by the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode).

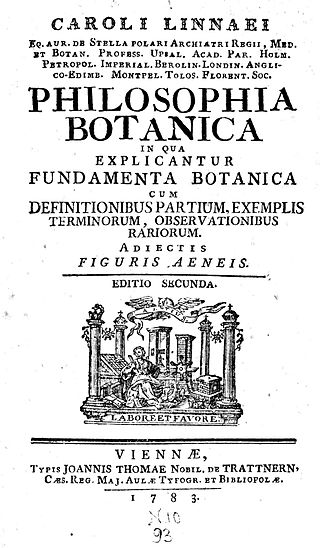

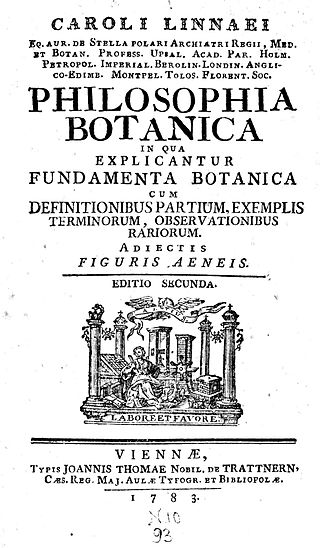

Philosophia Botanica was published by the Swedish naturalist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) who greatly influenced the development of botanical taxonomy and systematics in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is "the first textbook of descriptive systematic botany and botanical Latin". It also contains Linnaeus's first published description of his binomial nomenclature.

In biology, taxonomic rank is the relative level of a group of organisms in an ancestral or hereditary hierarchy. A common system of biological classification (taxonomy) consists of species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom, and domain. While older approaches to taxonomic classification were phenomenological, forming groups on the basis of similarities in appearance, organic structure and behaviour, methods based on genetic analysis have opened the road to cladistics.

Cultivated plant taxonomy is the study of the theory and practice of the science that identifies, describes, classifies, and names cultigens—those plants whose origin or selection is primarily due to intentional human activity. Cultivated plant taxonomists do, however, work with all kinds of plants in cultivation.

Critica Botanica was written by Swedish botanist, physician, zoologist and naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). The book was published in Germany when Linnaeus was 29 with a discursus by the botanist Johannes Browallius (1707–1755), bishop of Åbo. The first edition was published in July 1737 under the full title Critica botanica in qua nomina plantarum generica, specifica & variantia examini subjiciuntur, selectoria confirmantur, indigna rejiciuntur; simulque doctrina circa denominationem plantarum traditur. Seu Fundamentorum botanicorum pars IV Accedit Johannis Browallii De necessitate historiae naturalis discursus.