Related Research Articles

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in psychology that examines cognition and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify human psychological adaptations with regards to the ancestral problems they evolved to solve. In this framework, psychological traits and mechanisms are either functional products of natural and sexual selection or non-adaptive by-products of other adaptive traits.

Jerry Alan Fodor was an American philosopher and the author of many crucial works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His writings in these fields laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, and he is recognized as having had "an enormous influence on virtually every portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960." At the time of his death in 2017, he held the position of State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Rutgers University, and had taught previously at the City University of New York Graduate Center and MIT.

The Wason selection task is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966. It is one of the most famous tasks in the study of deductive reasoning. An example of the puzzle is:

You are shown a set of four cards placed on a table, each of which has a number on one side and a color on the other. The visible faces of the cards show 3, 8, blue and red. Which card(s) must you turn over in order to test that if a card shows an even number on one face, then its opposite face is blue?

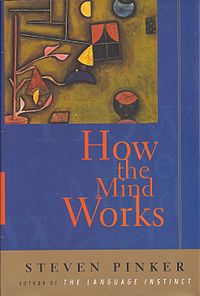

How the Mind Works is a 1997 book by the Canadian-American cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker, in which the author attempts to explain some of the human mind's poorly understood functions and quirks in evolutionary terms. Drawing heavily on the paradigm of evolutionary psychology articulated by John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, Pinker covers subjects such as vision, emotion, feminism, and "the meaning of life". He argues for both a computational theory of mind and a neo-Darwinist, adaptationist approach to evolution, all of which he sees as the central components of evolutionary psychology. He criticizes difference feminism because he believes scientific research has shown that women and men differ little or not at all in their moral reasoning. The book was a Pulitzer Prize Finalist.

The language module or language faculty is a hypothetical structure in the human brain which is thought to contain innate capacities for language, originally posited by Noam Chomsky. There is ongoing research into brain modularity in the fields of cognitive science and neuroscience, although the current idea is much weaker than what was proposed by Chomsky and Jerry Fodor in the 1980s. In today's terminology, 'modularity' refers to specialisation: language processing is specialised in the brain to the extent that it occurs partially in different areas than other types of information processing such as visual input. The current view is, then, that language is neither compartmentalised nor based on general principles of processing. It is modular to the extent that it constitutes a specific cognitive skill or area in cognition.

The term standard social science model (SSSM) was first introduced by John Tooby and Leda Cosmides in the 1992 edited volume The Adapted Mind. They used SSSM as a reference to social science philosophies related to the blank slate, relativism, social constructionism, and cultural determinism. They argue that those philosophies, capsulized within SSSM, formed the dominant theoretical paradigm in the development of the social sciences during the 20th century. According to their proposed SSSM paradigm, the mind is a general-purpose cognitive device shaped almost entirely by culture.

Cognitive specialization suggests that certain behaviors, often in the domain of social communication, are passed on to offspring and refined to be maximally beneficial by the process of natural selection. Specializations serve an adaptive purpose for an organism by allowing the organism to be better suited for its habitat. Over time, specializations often become essential to the species' continued survival. Cognitive specialization in humans has been thought to underlie the acquisition, development, and evolution of language, theory of mind, and specific social skills such as trust and reciprocity. These specializations are considered to be critical to the survival of the species, even though there are successful individuals who lack certain specializations, including those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder or who lack language abilities. Cognitive specialization is also believed to underlie adaptive behaviors such as self-awareness, navigation, and problem solving skills in several animal species such as chimpanzees and bottlenose dolphins.

Evolutionary developmental psychology (EDP) is a research paradigm that applies the basic principles of evolution by natural selection, to understand the development of human behavior and cognition. It involves the study of both the genetic and environmental mechanisms that underlie the development of social and cognitive competencies, as well as the epigenetic processes that adapt these competencies to local conditions.

The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture is a 1992 book edited by the anthropologists Jerome H. Barkow and John Tooby and the psychologist Leda Cosmides. First published by Oxford University Press, it is widely considered the foundational text of evolutionary psychology (EP), and outlines Cosmides and Tooby's integration of concepts from evolutionary biology and cognitive psychology, as well as many other concepts that would become important in adaptationist research.

Evolutionary educational psychology is the study of the relation between inherent folk knowledge and abilities and accompanying inferential and attributional biases as these influence academic learning in evolutionarily novel cultural contexts, such as schools and the industrial workplace. The fundamental premises and principles of this discipline are presented below.

Neuroconstructivism is a theory that states that phylogenetic developmental processes such as gene–gene interaction, gene–environment interaction and, crucially, ontogeny all play a vital role in how the brain progressively sculpts itself and how it gradually becomes specialized over developmental time.

Domain specificity is a theoretical position in cognitive science that argues that many aspects of cognition are supported by specialized, presumably evolutionarily specified, learning devices. The position is a close relative of modularity of mind, but is considered more general in that it does not necessarily entail all the assumptions of Fodorian modularity. Instead, it is properly described as a variant of psychological nativism. Other cognitive scientists also hold the mind to be modular, without the modules necessarily possessing the characteristics of Fodorian modularity.

Evolutionary psychology seeks to identify and understand human psychological traits that have evolved in much the same way as biological traits, through adaptation to environmental cues. Furthermore, it tends toward viewing the vast majority of psychological traits, certainly the most important ones, as the result of past adaptions, which has generated significant controversy and criticism from competing fields. These criticisms include disputes about the testability of evolutionary hypotheses, cognitive assumptions such as massive modularity, vagueness stemming from assumptions about the environment that leads to evolutionary adaptation, the importance of non-genetic and non-adaptive explanations, as well as political and ethical issues in the field itself.

A cognitive module in cognitive psychology is a specialized tool or sub-unit that can be used by other parts to resolve cognitive tasks. It is used in theories of the modularity of mind and the closely related society of mind theory and was developed by Jerry Fodor. It became better known throughout cognitive psychology by means of his book, The Modularity of Mind (1983). The nine aspects he lists that make up a mental module are domain specificity, mandatory operation, limited central accessibility, fast processing, informational encapsulation, "shallow" outputs, fixed neural architecture, characteristic and specific breakdown patterns, and characteristic ontogenetic pace and sequencing. Not all of these are necessary for the unit to be considered a module, but they serve as general parameters.

Cognitive description is a term used in psychology to describe the cognitive workings of the human mind.

Peter Carruthers is a British-American philosopher and cognitive scientist working primarily in the area of philosophy of mind, though he has also made contributions to philosophy of language and ethics. He is a professor of philosophy at the University of Maryland, College Park, an associate member of Neuroscience and Cognitive Science Program, and a member of the Committee for Philosophy and the Sciences.

Domain-general learning theories of development suggest that humans are born with mechanisms in the brain that exist to support and guide learning on a broad level, regardless of the type of information being learned. Domain-general learning theories also recognize that although learning different types of new information may be processed in the same way and in the same areas of the brain, different domains also function interdependently. Because these generalized domains work together, skills developed from one learned activity may translate into benefits with skills not yet learned. Another facet of domain-general learning theories is that knowledge within domains is cumulative, and builds under these domains over time to contribute to our greater knowledge structure. Psychologists whose theories align with domain-general framework include developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, who theorized that people develop a global knowledge structure which contains cohesive, whole knowledge internalized from experience, and psychologist Charles Spearman, whose work led to a theory on the existence of a single factor accounting for all general cognitive ability.

Domain-specific learning theories of development hold that we have many independent, specialised knowledge structures (domains), rather than one cohesive knowledge structure. Thus, training in one domain may not impact another independent domain. Domain-general views instead suggest that children possess a "general developmental function" where skills are interrelated through a single cognitive system. Therefore, whereas domain-general theories would propose that acquisition of language and mathematical skill are developed by the same broad set of cognitive skills, domain-specific theories would propose that they are genetically, neurologically and computationally independent.

Epidemiology of representations, or cultural epidemiology, is a theory for explaining cultural phenomena by examining how mental representations get distributed within a population. The theory uses medical epidemiology as its chief analogy, because "...macro-phenomena such as endemic and epidemic diseases are unpacked in terms of patterns of micro-phenomena of individual pathology and inter-individual transmission". Representations transfer via so-called "cognitive causal chains" ; these representations constitute a cultural phenomenon by achieving stability of public production and mental representation within the existing ecology and psychology of a populace, the latter including properties of the human mind. Cultural epidemiologists have emphasized the significance of evolved properties, such as the existence of naïve theories, domain-specific abilities and principles of relevance.

Evolutionary psychology has traditionally focused on individual-level behaviors, determined by species-typical psychological adaptations. Considerable work, though, has been done on how these adaptations shape and, ultimately govern, culture. Tooby and Cosmides (1989) argued that the mind consists of many domain-specific psychological adaptations, some of which may constrain what cultural material is learned or taught. As opposed to a domain-general cultural acquisition program, where an individual passively receives culturally-transmitted material from the group, Tooby and Cosmides (1989), among others, argue that: "the psyche evolved to generate adaptive rather than repetitive behavior, and hence critically analyzes the behavior of those surrounding it in highly structured and patterned ways, to be used as a rich source of information out of which to construct a 'private culture' or individually tailored adaptive system; in consequence, this system may or may not mirror the behavior of others in any given respect.".

References

- ↑ Robbins, Philip (August 21, 2017). "Modularity of Mind". Standard Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Goldstein, E. Bruce (17 June 2014). Cognitive Psychology. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-285-76388-0.

- 1 2 Fodor, Jerry A. (1983). Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56025-9

- 1 2 3 Hergenhahn, B. R., 1934-2007. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology (6th ed.). Australia: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-50621-8. OCLC 234363300.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Laurence, Stephen (2001). "The Poverty of the Stimulus Argument". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 52 (2): 217–276. doi:10.1093/bjps/52.2.217.

- ↑ Donaldson, J (2017). "Muller Lyer". The Illusions Index.

- ↑ Pylyshyn, Z.W. (1999). "Is vision continuous with cognition? The case for cognitive impenetrability of visual perception" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 22 (3): 341–423. doi:10.1017/S0140525X99002022. PMID 11301517. S2CID 9482993. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Frankenhuis, W. E.; Ploeger, A. (2007). "Evolutionary Psychology Versus Fodor: Arguments for and Against the Massive Modularity Hypothesis". Philosophical Psychology. 20 (6): 687. doi:10.1080/09515080701665904. S2CID 96445244.

- ↑ Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. (1994). Origins of Domain Specificity: The Evolution of Functional Organization. In L.A. Hirschfeld and S.A. Gelmen, eds., Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted in R. Cummins and D.D. Cummins, eds., Minds, Brains, and Computers. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000, 523-543.

- ↑ Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). Cognitive Adaptations for Social Exchange. In Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby 1992, 163-228.

- ↑ Samuels, Richard (1998). "Evolutionary Psychology and the Massive Modularity Hypothesis". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 49 (4): 575–602. doi:10.1093/bjps/49.4.575. JSTOR 688132.

- ↑ Confer, J. C.; Easton, J. A.; Fleischman, D. S.; Goetz, C. D.; Lewis, D. M. G.; Perilloux, C.; Buss, D. M. (2010). "Evolutionary psychology: Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations" (PDF). American Psychologist. 65 (2): 110–126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.601.8691 . doi:10.1037/a0018413. PMID 20141266.

- ↑ Clune, Jeff; Mouret, Jean-Baptiste; Lipson, Hod (2013). "The evolutionary origins of modularity". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 280 (1755): 20122863. arXiv: 1207.2743 . doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2863. PMC 3574393 . PMID 23363632.

- 1 2 3 Panksepp, J. & Panksepp, J. (2000). The Seven Sins of Evolutionary Psychology. Evolution and Cognition, 6:2, 108-131.

- ↑ Buller, David J. and Valerie Gray Hardcastle (2005) Chapter 4. "Modularity", in Buller, David J. The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology. The MIT Press. pp. 127 - 201

- 1 2 Davies, Paul Sheldon; Fetzer, James H.; Foster, Thomas R. (1995). "Logical reasoning and domain specificity". Biology and Philosophy . 10 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1007/BF00851985. S2CID 83429932.

- ↑ O'Brien, David; Manfrinati, Angela (2010). "The Mental Logic Theory of Conditional Propositions". In Oaksford, Mike; Chater, Nick (eds.). Cognition and Conditionals: Probability and Logic in Human Thinking. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–54. ISBN 978-0-19-923329-8.

- ↑ Lloyd, Elizabeth A. (1999). "Evolutionary Psychology: The Burdens of Proof" (PDF). Biology and Philosophy. 19 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1023/A:1006638501739. S2CID 1929648 . Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ Peters, Brad M. (2013). http://modernpsychologist.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/EP-Neglecting-Neurobiology-in-Defining-the-Mind1.pdf (PDF) Theory & Psychology https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0959354313480269

- ↑ Wallace, B. (2010). Getting Darwin Wrong: Why Evolutionary Psychology Won’t Work. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic.

- ↑ Buller, David J. (2005). "Evolutionary psychology: the emperor's new paradigm" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (6): 277–283. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.04.003. hdl: 10843/13182 . PMID 15925806. S2CID 6901180 . Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ Buller, David J.; Hardcastle, Valerie (2000). "Evolutionary Psychology, Meet Developmental Neurobiology: Against Promiscuous Modularity" (PDF). Brain and Mind. 1 (3): 307–325. doi:10.1023/A:1011573226794. S2CID 5664009 . Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ Buller, David J. (2005). "Get Over: Massive Modularity" (PDF). Biology & Philosophy. 20 (4): 881–891. doi:10.1007/s10539-004-1602-3. S2CID 34306536. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ↑ Uttal, William R. (2003). The New Phrenology: The Limits of Localizing Cognitive Processes in the Brain. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ↑ Donald, A Mind So Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness .