Within the realm of communication studies, organizational communication is a field of study surrounding all areas of communication and information flow that contribute to the functioning of an organization. Organizational communication is constantly evolving and as a result, the scope of organizations included in this field of research have also shifted over time. Now both traditionally profitable companies, as well as NGO's and non-profit organizations, are points of interest for scholars focused on the field of organizational communication. Organizations are formed and sustained through continuous communication between members of the organization and both internal and external sub-groups who possess shared objectives for the organization. The flow of communication encompasses internal and external stakeholders and can be formal or informal.

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) is defined as any human communication that occurs through the use of two or more electronic devices. While the term has traditionally referred to those communications that occur via computer-mediated formats, it has also been applied to other forms of text-based interaction such as text messaging. Research on CMC focuses largely on the social effects of different computer-supported communication technologies. Many recent studies involve Internet-based social networking supported by social software.

Social cognition is a topic within psychology that focuses on how people process, store, and apply information about other people and social situations. It focuses on the role that cognitive processes play in social interactions.

Nonverbal communication (NVC) is the transmission of messages or signals through a nonverbal platform such as eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, posture, use of objects and body language. It includes the use of social cues, kinesics, distance (proxemics) and physical environments/appearance, of voice (paralanguage) and of touch (haptics). A signal has three different parts to it, including the basic signal, what the signal is trying to convey, and how it is interpreted. These signals that are transmitted to the receiver depend highly on the knowledge and empathy that this individual has. It can also include the use of time (chronemics) and eye contact and the actions of looking while talking and listening, frequency of glances, patterns of fixation, pupil dilation, and blink rate (oculesics).

Theories of technological change and innovation attempt to explain the factors that shape technological innovation as well as the impact of technology on society and culture. Some of the most contemporary theories of technological change reject two of the previous views: the linear model of technological innovation and other, the technological determinism. To challenge the linear model, some of today's theories of technological change and innovation point to the history of technology, where they find evidence that technological innovation often gives rise to new scientific fields, and emphasizes the important role that social networks and cultural values play in creating and shaping technological artifacts. To challenge the so-called "technological determinism", today's theories of technological change emphasize the scope of the need of technical choice, which they find to be greater than most laypeople can realize; as scientists in philosophy of science, and further science and technology often like to say about this "It could have been different." For this reason, theorists who take these positions often argue that a greater public involvement in technological decision-making is desired.

Social behavior is behavior among two or more organisms within the same species, and encompasses any behavior in which one member affects the other. This is due to an interaction among those members. Social behavior can be seen as similar to an exchange of goods, with the expectation that when you give, you will receive the same. This behavior can be affected by both the qualities of the individual and the environmental (situational) factors. Therefore, social behavior arises as a result of an interaction between the two—the organism and its environment. This means that, in regards to humans, social behavior can be determined by both the individual characteristics of the person, and the situation they are in.

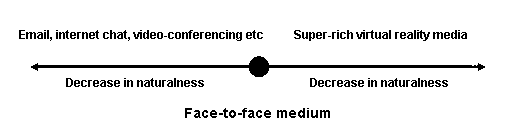

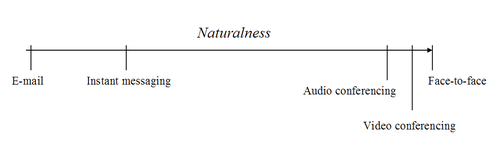

Media richness theory, sometimes referred to as information richness theory or MRT, is a framework used to describe a communication medium's ability to reproduce the information sent over it. It was introduced by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel in 1986 as an extension of information processing theory. MRT is used to rank and evaluate the richness of certain communication media, such as phone calls, video conferencing, and email. For example, a phone call cannot reproduce visual social cues such as gestures which makes it a less rich communication media than video conferencing, which affords the transmission of gestures and body language. Based on contingency theory and information processing theory, MRT theorizes that richer, personal communication media are generally more effective for communicating equivocal issues in contrast with leaner, less rich media.

Cognitive specialization suggests that certain behaviors, often in the domain of social communication, are passed on to offspring and refined to be maximally beneficial by the process of natural selection. Specializations serve an adaptive purpose for an organism by allowing the organism to be better suited for its habitat. Over time, specializations often become essential to the species' continued survival. Cognitive specialization in humans has been thought to underlie the acquisition, development, and evolution of language, theory of mind, and specific social skills such as trust and reciprocity. These specializations are considered to be critical to the survival of the species, even though there are successful individuals who lack certain specializations, including those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder or who lack language abilities. Cognitive specialization is also believed to underlie adaptive behaviors such as self-awareness, navigation, and problem solving skills in several animal species such as chimpanzees and bottlenose dolphins.

Presence is a theoretical concept describing the extent to which media represent the world. Presence is further described by Matthew Lombard and Theresa Ditton as “an illusion that a mediated experience is not mediated." Today, it often considers the effect that people experience when they interact with a computer-mediated or computer-generated environment. The conceptualization of presence borrows from multiple fields including communication, computer science, psychology, science, engineering, philosophy, and the arts. The concept of presence accounts for a variety of computer applications and Web-based entertainment today that are developed on the fundamentals of the phenomenon, in order to give people the sense of, as Sheridan called it, “being there."

Social information processing theory, also known as SIP, is a psychological and sociological theory originally developed by Salancik and Pfeffer in 1978. This theory explores how individuals make decisions and form attitudes in a social context, often focusing on the workplace. It suggests that people rely heavily on the social information available to them in their environments, including input from colleagues and peers, to shape their attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions.

The hyperpersonal model is a model of interpersonal communication that suggests computer-mediated communication (CMC) can become hyperpersonal because it "exceeds [face-to-face] interaction", thus affording message senders a host of communicative advantages over traditional face-to-face (FtF) interaction. The hyperpersonal model demonstrates how individuals communicate uniquely, while representing themselves to others, how others interpret them, and how the interactions create a reciprocal spiral of FtF communication. Compared to ordinary FtF situations, a hyperpersonal message sender has a greater ability to strategically develop and edit self-presentation, enabling a selective and optimized presentation of one's self to others.

Nereu Florencio "Ned" Kock is a Brazilian-American philosopher. He is a Texas A&M Regents Professor of Information Systems at Texas A&M International University.

Social presence theory explores how the "sense of being with another" is influenced by digital interfaces in human-computer interactions. Developed from the foundations of interpersonal communication and symbolic interactionism, social presence theory was first formally introduced by John Short, Ederyn Williams, and Bruce Christie in The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. Research on social presence theory has recently developed to examine the efficacy of telecommunications media, including SNS communications. The theory notes that computer-based communication is lower in social presence than face-to-face communication, but different computer-based communications can affect the levels of social presence between communicators and receivers.

Affective haptics is the emerging area of research which focuses on the study and design of devices and systems that can elicit, enhance, or influence the emotional state of a human by means of sense of touch. The research field is originated with the Dzmitry Tsetserukou and Alena Neviarouskaya papers on affective haptics and real-time communication system with rich emotional and haptic channels. Driven by the motivation to enhance social interactivity and emotionally immersive experience of users of real-time messaging, virtual, augmented realities, the idea of reinforcing (intensifying) own feelings and reproducing (simulating) the emotions felt by the partner was proposed. Four basic haptic (tactile) channels governing our emotions can be distinguished:

- physiological changes

- physical stimulation

- social touch

- emotional haptic design.

Interpersonal communication is an exchange of information between two or more people. It is also an area of research that seeks to understand how humans use verbal and nonverbal cues to accomplish a number of personal and relational goals.

Channel expansion theory (CET) states that individual experience serves as an important role in determining the level of richness perception and development towards certain media tools. It is a theory of communication media perception that incorporates experiential factors to explain and predict user perceptions of a given media channel. The theory suggests that the more knowledge and experience users gain from using a channel, the richer they perceive the medium to be. The more experience, the more stable the knowledge base the person builds, the more knowledge he gains from the given media channel, thus the richer communication he would have using that channel, and ultimately the richer he would perceive the channel. There are four experiential factors that shapes individual's perceived media richness: experience with the channel, experience with the message topic, experience with the organizational context, and experience with a communication partner.

Multi-communicating is the act of managing many conversations at one time. The term was coined by Reinsch, Turner, and Tinsley (2008), who proposed that simultaneous conversations can be conducted using an ever-increasing array of media, including face-to-face, phone, and email tools for communication. This practice allows individuals to utilize two or more technologies to interact with each other.

Emotions in virtual communication are expressed and understood in a variety of different ways from those in face-to-face interactions. Virtual communication continues to evolve as technological advances emerge that give way to new possibilities in computer-mediated communication (CMC). The lack of typical auditory and visual cues associated with human emotion gives rise to alternative forms of emotional expression that are cohesive with many different virtual environments. Some environments provide only space for text based communication, where emotions can only be expressed using words. More newly developed forms of expression provide users the opportunity to portray their emotions using images.

Mediated communication or mediated interaction refers to communication carried out by the use of information communication technology and can be contrasted to face-to-face communication. While nowadays the technology we use is often related to computers, giving rise to the popular term computer-mediated communication, mediated technology need not be computerized as writing a letter using a pen and a piece of paper is also using mediated communication. Thus, Davis defines mediated communication as the use of any technical medium for transmission across time and space.

Nonverbal autism is a subset of autism spectrum where the person does not learn how to speak. It is estimated that 25% to 50% of children diagnosed with autism spectrum never develop spoken language beyond a few words or utterances.