Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes with input from linguistics, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, computer science/artificial intelligence, and anthropology. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition. Cognitive scientists study intelligence and behavior, with a focus on how nervous systems represent, process, and transform information. Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include language, perception, memory, attention, reasoning, and emotion; to understand these faculties, cognitive scientists borrow from fields such as linguistics, psychology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, neuroscience, and anthropology. The typical analysis of cognitive science spans many levels of organization, from learning and decision to logic and planning; from neural circuitry to modular brain organization. One of the fundamental concepts of cognitive science is that "thinking can best be understood in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures."

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Social cognition is a topic within psychology that focuses on how people process, store, and apply information about other people and social situations. It focuses on the role that cognitive processes play in social interactions.

In the philosophy of mind, neuroscience, and cognitive science, a mental image is an experience that, on most occasions, significantly resembles the experience of "perceiving" some object, event, or scene but occurs when the relevant object, event, or scene is not actually present to the senses. There are sometimes episodes, particularly on falling asleep and waking up, when the mental imagery may be dynamic, phantasmagoric, and involuntary in character, repeatedly presenting identifiable objects or actions, spilling over from waking events, or defying perception, presenting a kaleidoscopic field, in which no distinct object can be discerned. Mental imagery can sometimes produce the same effects as would be produced by the behavior or experience imagined.

The consciousness and binding problem is the problem of how objects, background and abstract or emotional features are combined into a single experience.

Neuroesthetics is a relatively recent sub-discipline of applied aesthetics. Empirical aesthetics takes a scientific approach to the study of aesthetic experience of art, music, or any object that can give rise to aesthetic judgments. Neuroesthetics is a term coined by Semir Zeki in 1999 and received its formal definition in 2002 as the scientific study of the neural bases for the contemplation and creation of a work of art. Neuroesthetics uses neuroscience to explain and understand the aesthetic experiences at the neurological level. The topic attracts scholars from many disciplines including neuroscientists, art historians, artists, art therapists and psychologists.

Cognitive development is a field of study in neuroscience and psychology focusing on a child's development in terms of information processing, conceptual resources, perceptual skill, language learning, and other aspects of the developed adult brain and cognitive psychology. Qualitative differences between how a child processes their waking experience and how an adult processes their waking experience are acknowledged. Cognitive development is defined as the emergence of the ability to consciously cognize, understand, and articulate their understanding in adult terms. Cognitive development is how a person perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of their world through the relations of genetic and learning factors. There are four stages to cognitive information development. They are, reasoning, intelligence, language, and memory. These stages start when the baby is about 18 months old, they play with toys, listen to their parents speak, they watch TV, anything that catches their attention helps build their cognitive development.

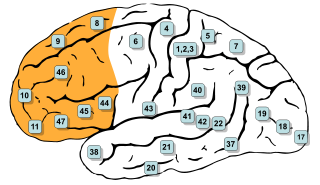

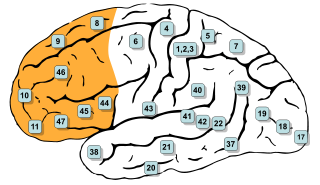

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

Developmental cognitive neuroscience is an interdisciplinary scientific field devoted to understanding psychological processes and their neurological bases in the developing organism. It examines how the mind changes as children grow up, interrelations between that and how the brain is changing, and environmental and biological influences on the developing mind and brain.

Cultural neuroscience is a field of research that focuses on the interrelation between a human's cultural environment and neurobiological systems. The field particularly incorporates ideas and perspectives from related domains like anthropology, psychology, and cognitive neuroscience to study sociocultural influences on human behaviors. Such impacts on behavior are often measured using various neuroimaging methods, through which cross-cultural variability in neural activity can be examined.

In neuroscience, functional specialization is a theory which suggests that different areas in the brain are specialized for different functions.

Educational neuroscience is an emerging scientific field that brings together researchers in cognitive neuroscience, developmental cognitive neuroscience, educational psychology, educational technology, education theory and other related disciplines to explore the interactions between biological processes and education. Researchers in educational neuroscience investigate the neural mechanisms of reading, numerical cognition, attention and their attendant difficulties including dyslexia, dyscalculia and ADHD as they relate to education. Researchers in this area may link basic findings in cognitive neuroscience with educational technology to help in curriculum implementation for mathematics education and reading education. The aim of educational neuroscience is to generate basic and applied research that will provide a new transdisciplinary account of learning and teaching, which is capable of informing education. A major goal of educational neuroscience is to bridge the gap between the two fields through a direct dialogue between researchers and educators, avoiding the "middlemen of the brain-based learning industry". These middlemen have a vested commercial interest in the selling of "neuromyths" and their supposed remedies.

Cognitive humor processing refers to the neural circuitry and pathways that are involved in detecting incongruities of various situations presented in a humorous manner. Over the past decade, many studies have emerged utilizing fMRI studies to describe the neural correlates associated with how a human processes something that is considered "funny". Conceptually, humor is subdivided into two elements: cognitive and affective. The cognitive element, known as humor detection, refers to understanding the joke. Usually, this is characterized by the perceiver attempting to comprehend the disparities between the punch line and prior experience. The affective element, otherwise known as humor appreciation, is involved with enjoying the joke and producing visceral, emotional responses depending on the hilarity of the joke. This ability to comprehend and appreciate humor is a vital aspect of social functioning and is a significant part of the human condition that is relevant from a very early age. Humor comprehension develops in parallel with growing cognitive and language skills during childhood, while its content is mostly influenced by social and cultural factors. A further approach is described which refers to humor as an attitude related to strains. Humorous responses when confronted with troubles are discussed as a skill often associated with high social competence. The concept of humor has also been shown to have therapeutic effects, improving physiological systems such as the immune and central nervous system. It also has been shown to help cope with stress and pain. In sum, humor proves to be a personal resource throughout the life span, and helps support the coping of everyday tasks.

Cultural variation refers to the rich diversity in social practices that different cultures exhibit around the world. Cuisine and art all change from one culture to the next, but so do gender roles, economic systems, and social hierarchy among any number of other humanly organised behaviours. Cultural variation can be studied across cultures or across generations and is often a subject studied by anthropologists, sociologists and cultural theorists with subspecialties in the fields of economic anthropology, ethnomusicology, health sociology etc. In recent years, cultural variation has become a rich source of study in neuroanthropology, cultural neuroscience, and social neuroscience.

Interindividual differences in perception describes the effect that differences in brain structure or factors such as culture, upbringing and environment have on the perception of humans. Interindividual variability is usually regarded as a source of noise for research. However, in recent years, it has become an interesting source to study sensory mechanisms and understand human behavior. With the help of modern neuroimaging methods such as fMRI and EEG, individual differences in perception could be related to the underlying brain mechanisms. This has helped to explain differences in behavior and cognition across the population. Common methods include studying the perception of illusions, as they can effectively demonstrate how different aspects such as culture, genetics and the environment can influence human behavior.

Prefrontal synthesis is the conscious purposeful process of synthesizing novel mental images. PFS is neurologically different from the other types of imagination, such as simple memory recall and dreaming. Unlike dreaming, which is spontaneous and not controlled by the prefrontal cortex (PFC), PFS is controlled by and completely dependent on the intact lateral prefrontal cortex. Unlike simple memory recall that involves activation of a single neuronal ensemble (NE) encoded at some point in the past, PFS involves active combination of two or more object-encoding neuronal ensembles (objectNE). The mechanism of PFS is hypothesized to involve synchronization of several independent objectNEs. When objectNEs fire out-of-sync, the objects are perceived one at a time. However, once those objectNEs are time-shifted by the lateral PFC to fire in-phase with each other, they are consciously experienced as one unified object or scene.

Neuromorality is an emerging field of neuroscience that studies the connection between morality and neuronal function. Scientists use fMRI and psychological assessment together to investigate the neural basis of moral cognition and behavior. Evidence shows that the central hub of morality is the prefrontal cortex guiding activity to other nodes of the neuromoral network. A spectrum of functional characteristics within this network to give rise to both altruistic and psychopathological behavior. Evidence from the investigation of neuromorality has applications in both clinical neuropsychiatry and forensic neuropsychiatry.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.