The Annales school is a group of historians associated with a style of historiography developed by French historians in the 20th century to stress long-term social history. It is named after its scholarly journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, which remains the main source of scholarship, along with many books and monographs. The school has been influential in setting the agenda for historiography in France and numerous other countries, especially regarding the use of social scientific methods by historians, emphasizing social and economic rather than political or diplomatic themes.

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic by using particular sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. Scholars discuss historiography by topic—such as the historiography of the United Kingdom, that of WWII, the pre-Columbian Americas, early Islam, and China—and different approaches and genres, such as political history and social history. Beginning in the nineteenth century, with the development of academic history, there developed a body of historiographic literature. The extent to which historians are influenced by their own groups and loyalties—such as to their nation state—remains a debated question.

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. Some historians are recognized by publications or training and experience. "Historian" became a professional occupation in the late nineteenth century as research universities were emerging in Germany and elsewhere.

Diplomatic history deals with the history of international relations between states. Diplomatic history can be different from international relations in that the former can concern itself with the foreign policy of one state while the latter deals with relations between two or more states. Diplomatic history tends to be more concerned with the history of diplomacy, but international relations concern more with current events and creating a model intended to shed explanatory light on international politics.

Social history, often called "history from below", is a field of history that looks at the lived experience of the past. Historians who write social history are called social historians. Social history came to prominence in the 1960s, with some arguing that its origins lie over a century earlier.

Frederick Jackson Turner was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thesis. He trained many PhDs who went on to become well-known historians. He promoted interdisciplinary and quantitative methods, often with an emphasis on the Midwestern United States.

Charles Austin Beard was an American historian and professor, who wrote primarily during the first half of the 20th century. A history professor at Columbia University, Beard's influence is primarily due to his publications in the fields of history and political science. His works included a radical re-evaluation of the Founding Fathers of the United States, whom he believed to be more motivated by economics than by philosophical principles. Beard's most influential book, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913), has been the subject of great controversy ever since its publication. While it has been frequently criticized for its methodology and conclusions, it was responsible for a wide-ranging reinterpretation of early American history.

Hans-Ulrich Wehler was a German left-liberal historian known for his role in promoting social history through the "Bielefeld School", and for his critical studies of 19th-century Germany.

Comparative history is the comparison of different societies which existed during the same time period or shared similar cultural conditions.

History is the systematic study and documentation of the human past.

As soon as the term "Cold War" was popularized to refer to postwar tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, interpreting the course and origins of the conflict became a source of heated controversy among historians, political scientists and journalists. In particular, historians have sharply disagreed as to who was responsible for the breakdown of Soviet Union–United States relations after the World War II and whether the conflict between the two superpowers was inevitable, or could have been avoided. Historians have also disagreed on what exactly the Cold War was, what the sources of the conflict were and how to disentangle patterns of action and reaction between the two sides. While the explanations of the origins of the conflict in academic discussions are complex and diverse, several general schools of thought on the subject can be identified. Historians commonly speak of three differing approaches to the study of the Cold War: "orthodox" accounts, "revisionism" and "post-revisionism". However, much of the historiography on the Cold War weaves together two or even all three of these broad categories and more recent scholars have tended to address issues that transcend the concerns of all three schools.

The historiography of the British Empire refers to the studies, sources, critical methods and interpretations used by scholars to develop a history of the British Empire. Historians and their ideas are the main focus here; specific lands and historical dates and episodes are covered in the article on the British Empire. Scholars have long studied the Empire, looking at the causes for its formation, its relations to the French and other empires, and the kinds of people who became imperialists or anti-imperialists, together with their mindsets. The history of the breakdown of the Empire has attracted scholars of the histories of the United States, the British Raj, and the African colonies. John Darwin (2013) identifies four imperial goals: colonising, civilising, converting, and commerce.

The Bielefeld School is a group of German historians based originally at Bielefeld University who promote social history and political history using quantification and the methods of political science and sociology. The leaders include Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Jürgen Kocka and Reinhart Koselleck. Instead of emphasizing the personalities of great historical leaders, as in the conventional approach, it concentrates on socio-cultural developments. History as "historical social science" has mainly been explored in the context of studies of German society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The movement has published the scholarly journal Geschichte und Gesellschaft: Zeitschrift fur Historische Sozialwissenschaft since 1975.

The historiography of the United States refers to the studies, sources, critical methods and interpretations used by scholars to study the history of the United States. While history examines the interplay of events in the past, historiography examines the secondary sources written by historians as books and articles, evaluates the primary sources they use, and provides a critical examination of the methodology of historical study.

Marxist historiography, or historical materialist historiography, is an influential school of historiography. The chief tenets of Marxist historiography include the centrality of social class, social relations of production in class-divided societies that struggle against each other, and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. Marxist historians follow the tenets of the development of class-divided societies, especially modern capitalist ones.

The historiography of Canada deals with the manner in which historians have depicted, analyzed, and debated the history of Canada. It also covers the popular memory of critical historical events, ideas and leaders, as well as the depiction of those events in museums, monuments, reenactments, pageants and historic sites.

The historiography of the United Kingdom includes the historical and archival research and writing on the history of the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. For studies of the overseas empire see historiography of the British Empire.

The historiography of Germany deals with the manner in which historians have depicted, analyzed and debated the history of Germany. It also covers the popular memory of critical historical events, ideas and leaders, as well as the depiction of those events in museums, monuments, reenactments, pageants and historic sites, and the editing of historical documents.

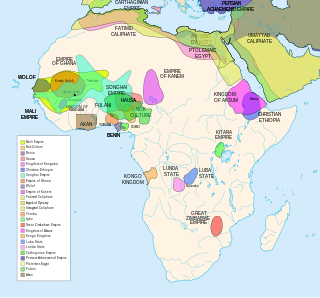

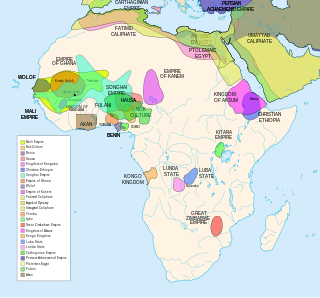

African historiography is a branch of historiography concerning the African continent, its peoples, nations and variety of written and non-written histories. It has differentiated itself from other continental areas of historiography due to its multidisciplinary nature, as Africa's unique and varied methods of recording history have resulted in a lack of an established set of historical works documenting events before European colonialism. As such, African historiography has lent itself to contemporary methods of historiographical study and the incorporation of anthropological and sociological analysis.

Political history in the United States covers the historiography or the methods used by political historians, political scientists, and other scholars in analyzing the history of politics in the United States.