Related Research Articles

Macbeth was King of Scotland (Alba) from 1040 until his death. Alba covered only a portion of present-day Scotland.

The Stone of Scone, also known as the Stone of Destiny, is an oblong block of red sandstone that was used originally in the coronation of the monarchs of Scotland and, after the 13th century, the coronation of the monarchs of England, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. It is also known as Jacob's Pillow Stone and the Tanist Stone, and as clach-na-cinneamhain in Scottish Gaelic.

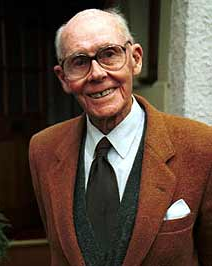

Nigel Tranter OBE was a writer of a wide range of books on castles, particularly on themes of architecture and history. He also specialised in deeply researched historical novels that cover centuries of Scottish history.

The Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton was a peace treaty signed in 1328 between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. It brought an end to the First War of Scottish Independence, which had begun with the English invasion of Scotland in 1296. The treaty was signed in Edinburgh by Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, on 17 March 1328, and was ratified by the Parliament of England meeting in Northampton on 1 May.

Ian Robertson Hamilton KC was a Scottish lawyer and nationalist, best known for his part in the return of the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey to Arbroath Abbey in 1950.

The Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, originally the Crown Jewels of England, are a collection of royal ceremonial objects kept in the Tower of London, which include the coronation regalia and vestments worn by British monarchs.

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th century.

The Honours of Scotland, informally known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, are the regalia that were worn by Scottish monarchs at their coronation. Kept in the Crown Room in Edinburgh Castle, they date from the 15th and 16th centuries, and are the oldest surviving set of crown jewels in the British Isles.

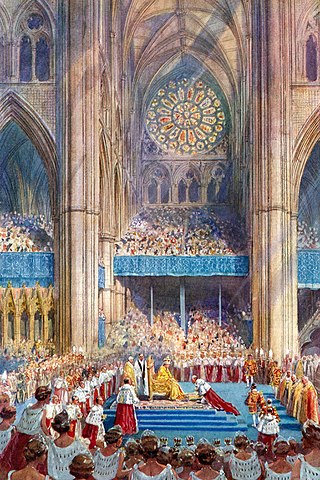

The coronation of the monarch of the United Kingdom is a ceremony in which they are formally invested with regalia and crowned at Westminster Abbey. It corresponds to the coronations that formerly took place in other European monarchies, all of which have abandoned coronations in favour of inauguration or enthronement ceremonies. A coronation is a symbolic formality and does not signify the official beginning of the monarch's reign; de jure and de facto their reign commences from the moment of the preceding monarch's death, maintaining the legal continuity of the monarchy.

The Coronation Chair, also known as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by King Edward I to contain the coronation stone of Scotland—known as the Stone of Destiny—which had been captured from the Scots. The chair was named after Edward the Confessor and was kept in his shrine at Westminster Abbey.

The Stone of Jacob appears in the Book of Genesis as the stone used as a pillow by the Israelite patriarch Jacob at the place later called Bet-El. As Jacob had a vision in his sleep, he then consecrated the stone to God. More recently, the stone has been claimed by Scottish folklore and British Israelism.

Scone Palace is a Category A-listed historic house near the village of Scone and the city of Perth, Scotland. Built in red sandstone with a castellated roof, it is an example of the Gothic Revival style in Scotland.

The Crown of Scotland is the centrepiece of the Honours of Scotland. It is the crown that was used at the coronation of the monarchs of Scotland, and is the oldest surviving crown in the British Isles and among the oldest in Europe.

Llywelyn's coronet is a lost treasure of Welsh history. It is recorded that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales and Lord of Aberffraw had deposited this crown and other items with the monks at Cymer Abbey for safekeeping at the start of his final campaign in 1282. He was killed later that year. It was seized alongside other holy artefacts in 1284 from the ruins of the defeated Kingdom of Gwynedd. Thereafter it was taken to London and presented at the shrine of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey by King Edward I of England as a token of the complete annihilation of the independent Welsh state.

Scone Abbey was a house of Augustinian canons located in Scone, Perthshire (Gowrie), Scotland. Dates given for the establishment of Scone Priory have ranged from 1114 A.D. to 1122 A.D. However, historians have long believed that Scone was before that time the center of the early medieval Christian cult of the Culdees. Very little is known about the Culdees but it is thought that a cult may have been worshiping at Scone from as early as 700 A.D. Archaeological surveys taken in 2007 suggest that Scone was a site of real significance even prior to 841 A.D., when Kenneth MacAlpin brought the Stone of Destiny, Scotland's most prized relic and coronation stone, to Scone.

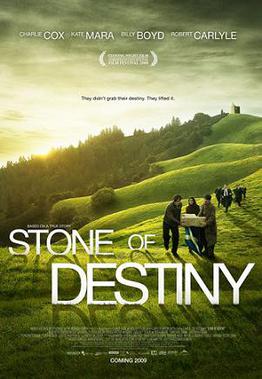

Stone of Destiny is a 2008 Scottish-Canadian historical adventure/comedy film written and directed by Charles Martin Smith and starring Charlie Cox, Billy Boyd, Robert Carlyle, and Kate Mara. Based on real events, the film tells the story of the removal of the Stone of Scone from Westminster Abbey. The stone, supposedly the Stone of Jacob over which Scottish monarchs were traditionally crowned at Scone in Perthshire, was taken by King Edward I of England in 1296 and placed under the throne at Westminster Abbey in London. In 1950, a group of Scottish nationalist students succeeded in liberating it from Westminster Abbey and returning it to Scotland where it was placed symbolically at Arbroath Abbey, the site of the signing of the Declaration of Arbroath and an important site in the Scottish nationalist cause.

Scone is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The medieval town of Scone, which grew up around the monastery and royal residence, was abandoned in the early 19th century when the residents were removed and a new palace was built on the site by the Earl of Mansfield. Hence the modern village of Scone, and the medieval village of Old Scone, can often be distinguished.

The Holyrood or Holy Rood is a Christian relic alleged to be part of the True Cross on which Jesus died. The word derives from the Old English rood, meaning a pole and the cross, via Middle English, or the Scots haly ruid. Several relics venerated as part of the True Cross are known by this name, in England, Ireland and Scotland.

On 25 December 1950, four Scottish students from the University of Glasgow stole the Stone of Scone from Westminster Abbey in London and took it back to Scotland. The students were members of the Scottish Covenant Association, a group that supported home rule for Scotland. In 2008, the incident was made into a film called Stone of Destiny. It seems likely that the escapade was based on the fictional account of a plot by Scottish Nationalists to liberate the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Cathedral and to return it to Scotland, as told in Compton Mackenzie's novel The North Wind of Love Bk.1, published six years earlier in 1944.

Robert Gray, often known as Bertie Gray, was a Scottish nationalist politician.

References

- ↑ Bradfield, Ray, Nigel Tranter: Scotland's Storyteller, p 121

- ↑ Tranter, Nigel, The Story of Scotland, p 11

- ↑ Tranter, Nigel, The Story of Scotland , Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987

- ↑ Bradfield, Ray, Nigel Tranter: Scotland's Storyteller, p 130

- 1 2 Prebble, John, The Lion in the North

- ↑ "The stone of Destiny". English Monarchs. www.englishmonarcs.co.uk. 2004–2005. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Tranter, Nigel, The Story of Scotland, p 77

- 1 2 The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph) Richard Welander, David J. Breeze, Thomas Owen Clancy

- ↑ Dunsinane Hill, fort, ancientmonuments.uk, accessed 10 June 2022

- 1 2 Bradfield, Ray, Nigel Tranter: Scotland's Storyteller, p 122

- ↑ "Gavin Vernon Engineer who helped return the Stone of Destiny to Scotland". The Herald (Glasgow) . 1 April 2004. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Erlend Clouston, 'Stone of Destiny proved genuine: Files reveal how in 1973 Scottish relic was X-rayed', The Guardian (17 July 1996), p. 4.