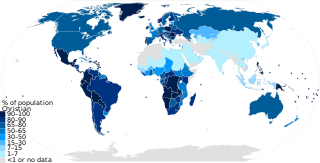

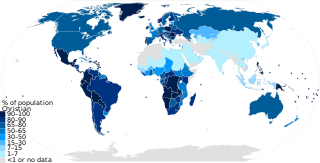

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian empires, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails, or that it is culturally or historically intertwined with.

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic by using particular sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. Scholars discuss historiography by topic—such as the historiography of the United Kingdom, that of WWII, the pre-Columbian Americas, early Islam, and China—and different approaches and genres, such as political history and social history. Beginning in the nineteenth century, with the development of academic history, there developed a body of historiographic literature. The extent to which historians are influenced by their own groups and loyalties—such as to their nation state—remains a debated question.

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. Some historians are recognized by publications or training and experience. "Historian" became a professional occupation in the late nineteenth century as research universities were emerging in Germany and elsewhere.

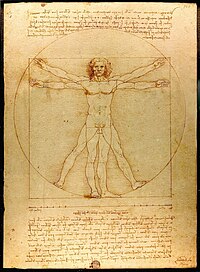

The Renaissance is a period in history and a cultural movement marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity, covering the 15th and 16th centuries and characterized by an effort to revive and surpass the ideas and achievements of classical antiquity; it occurred after the crisis of the Late Middle Ages and was associated with great social change in most fields and disciplines, including art, architecture, politics, literature, exploration and science. In addition to the standard periodization, proponents of a "long Renaissance" may put its beginning in the 14th century and its end in the 17th century.

Leonardo Bruni or Leonardo Aretino was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. He was the earliest person to write using the three-period view of history: Antiquity, Middle Ages, and Modern. The dates Bruni used to define the periods are not exactly what modern historians use today, but he laid the conceptual groundwork for a tripartite division of history.

An antiquarian or antiquary is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifacts, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts. The essence of antiquarianism is a focus on the empirical evidence of the past, and is perhaps best encapsulated in the motto adopted by the 18th-century antiquary Sir Richard Colt Hoare, "We speak from facts, not theory."

Renaissance humanism was a worldview centered on the nature and importance of humanity, that emerged from the study of Classical antiquity. This first began in Italy and then spread across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term humanist referred to teachers and students of the humanities, known as the studia humanitatis, which included the study of Latin and Ancient Greek literatures, grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. It was not until the 19th century that this began to be called humanism instead of the original humanities, and later by the retronym Renaissance humanism to distinguish it from later humanist developments. During the Renaissance period most humanists were Christians, so their concern was to "purify and renew Christianity", not to do away with it. Their vision was to return ad fontes to the simplicity of the Gospels and of the New Testament, bypassing the complexities of medieval Christian theology.

Polemic is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial topics. A person who writes polemics, or speaks polemically, is called a polemicist. The word derives from Ancient Greek πολεμικός 'warlike, hostile', from πόλεμος 'war'.

The Latin school was the grammar school of 14th- to 19th-century Europe, though the latter term was much more common in England. Other terms used include Lateinschule in Germany, or later Gymnasium. Latin schools were also established in Colonial America.

The designation "Renaissance philosophy" is used by historians of philosophy to refer to the thought of the period running in Europe roughly between 1400 and 1600. It therefore overlaps both with late medieval philosophy, which in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was influenced by notable figures such as Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, and Marsilius of Padua, and early modern philosophy, which conventionally starts with René Descartes and his publication of the Discourse on Method in 1637.

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity, individual freedom, and the importance of happiness as essential and principal or even exclusive components of the teachings of Jesus. Proponents of the term trace the concept to the Renaissance or patristic period, linking their beliefs to the scholarly movement also called 'humanism'.

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to humanism:

Hans Baron was a German-American historian of political thought and literature. His main contribution to the historiography of the period was to introduce in 1928 the term civic humanism.

Albertino Mussato (1261–1329) was a statesman, poet, historian and playwright from Padua. He is credited with providing an impetus to the revival of literary Latin, and is characterized as an early humanist. He was influenced by his teacher, the Paduan poet and proto-humanist Lovato Lovati. Mussato influenced many humanists such as Petrarch.

Pietro Ranzano was an Italian Dominican friar, bishop, historian, humanist and scholar who is best known for his work, De primordiis et progressu felicis Urbis Panormi, a history of the city of Palermo from its beginnings up until the contemporary period in which Ranzano was writing. The composition is influenced to some extent by humanistic conceptions of historical research, offers glimpses into the world view of a Sicilian intellectual of the Renaissance period on Jews and Jewish culture, as well as Sicily’s past.

Humanist minuscule is a handwriting or style of script that was invented in secular circles in Italy, at the beginning of the fifteenth century. "Few periods in Western history have produced writing of such great beauty", observes the art historian Millard Meiss. The new hand was based on Carolingian minuscule, which Renaissance humanists, obsessed with the revival of antiquity and their role as its inheritors, took to be ancient Roman:

[W]hen they handled manuscript books copied by eleventh- and twelfth-century scribes, Quattrocento literati thought they were looking at texts that came right out of the bookshops of ancient Rome".

The medieval renaissances were periods characterised by significant cultural renewal across medieval Western Europe. These are effectively seen as occurring in three phases - the Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Lovato Lovati (1241–1309) was an Italian scholar, poet, notary, judge and humanist from the High Middle Ages and early Italian Renaissance. Arguable among historians, Lovati is considered the "father of Humanism." His literary Padua circle included Rolando de Piazzola, Geremia da Montagnone, and Albertino Mussato. Lovati's scholarship marked characteristics which would later define the development of humanism: an appetite for classical texts; a philological concern to correct them, and ascertain their meaning; and a desire to imitate them. Scholars such as Petrarch commented on his works favorably. Lovati's achievements which survive today are his Latin verse epistles, and his short commentary of Seneca's tragedies.