The Renaissance is a period in history and a cultural movement marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity, covering the 15th and 16th centuries and characterized by an effort to revive and surpass the ideas and achievements of classical antiquity; it was associated with great social change in most fields and disciplines, including art, architecture, politics, literature, exploration and science. It began in the Republic of Florence, then spread to the rest of Italy and later throughout Europe. The term rinascita ("rebirth") first appeared in Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari, while the corresponding French word renaissance was adopted into English as the term for this period during the 1830s.

Rodolphus Agricola was a Dutch humanist of the Northern Low Countries, famous for his knowledge of Latin and Greek. He was an educator, musician, builder of church organs, a poet in Latin and the vernacular, a diplomat, a boxer and a Hebrew scholar towards the end of his life. Today, he is best known as the author of De inventione dialectica, the father of Northern European humanism and a zealous anti-scholastic in the late fifteenth century.

Bessarion was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letters in the 15th century.

George of Trebizond was a Byzantine Greek philosopher, scholar, and humanist.

The Donation of Constantine is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the 4th-century emperor Constantine the Great supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the Pope. Composed probably in the 8th century, it was used, especially in the 13th century, in support of claims of political authority by the papacy.

Translatio imperii is a historiographical concept that was prominent in the Middle Ages in the thinking and writing of elite groups of the population in Europe, but was the reception of a concept from antiquity. In this concept the proces of decline and fall of an empire theoretically is being replaced by a natural succession from one empire to another. Translatio implies that an empire metahistorically can be transferred from hand to hand and place to place, from Troy to Romans and Greeks to Franks and further on to Spain, and has therefore survived.

Renaissance humanism was a worldview centered on the nature and importance of humanity, that emerged from the study of Classical antiquity. This first began in Italy and then spread across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term humanist referred to teachers and students of the humanities, known as the studia humanitatis, which included the study of Latin and Ancient Greek literatures, grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. It was not until the 19th century that this began to be called humanism instead of the original humanities, and later by the retronym Renaissance humanism to distinguish it from later humanist developments. During the Renaissance period most humanists were Christians, so their concern was to "purify and renew Christianity", not to do away with it. Their vision was to return ad fontes to the simplicity of the Gospels and of the New Testament, bypassing the complexities of medieval Christian theology.

Oedipus Aegyptiacus is Athanasius Kircher's supreme work of Egyptology.

Lorenzo Valla was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator and scholar. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery, therefore attacking and undermining the presumption of temporal power claimed by the papacy. Lorenzo is sometimes seen as a precursor of the Reformation.

Theodorus Gaza, also called Theodore Gazis or by the epithet Thessalonicensis and Thessalonikeus, was a Greek humanist and translator of Aristotle, one of the Greek scholars who were the leaders of the revival of learning in the 15th century.

Demetrios Chalkokondyles, Latinized as Demetrius Chalcocondyles and found variously as Demetricocondyles, Chalcocondylas or Chalcondyles was one of the most eminent Greek scholars in the West. He taught in Italy for over forty years; his colleagues included Marsilio Ficino, Poliziano, and Theodorus Gaza in the revival of letters in the Western world, and Chalkokondyles was the last of the Greek humanists who taught Greek literature at the great universities of the Italian Renaissance. One of his pupils at Florence was the famous Johann Reuchlin. Chalkokondyles published the first printed publications of Homer, of Isocrates, and of the Suda lexicon.

Intertextuality is the shaping of a text's meaning by another text, either through deliberate compositional strategies such as quotation, allusion, calque, plagiarism, translation, pastiche or parody, or by interconnections between similar or related works perceived by an audience or reader of the text. These references are sometimes made deliberately and depend on a reader's prior knowledge and understanding of the referent, but the effect of intertextuality is not always intentional and is sometimes inadvertent. Often associated with strategies employed by writers working in imaginative registers, intertextuality may now be understood as intrinsic to any text.

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the invention of printing allowed a faster propagation of new ideas. Nevertheless, some have seen the Renaissance, at least in its initial period, as one of scientific backwardness. Historians like George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike criticized how the Renaissance affected science, arguing that progress was slowed for some amount of time. Humanists favored human-centered subjects like politics and history over study of natural philosophy or applied mathematics. More recently, however, scholars have acknowledged the positive influence of the Renaissance on mathematics and science, pointing to factors like the rediscovery of lost or obscure texts and the increased emphasis on the study of language and the correct reading of texts.

In textual and classical scholarship, the editio princeps of a work is the first printed edition of the work, that previously had existed only in manuscripts. These had to be copied by hand in order to circulate.

The transmission of the Greek Classics to Latin Western Europe during the Middle Ages was a key factor in the development of intellectual life in Western Europe. Interest in Greek texts and their availability was scarce in the Latin West during the Early Middle Ages, but as traffic to the East increased, so did Western scholarship.

Francus is a mythological figure of French medieval historians which referred to a legendary eponymous king of the Franks, a descendant of the Trojans, founder of the Merovingian dynasty and forefather of Charlemagne. In the Renaissance, Francus was generally considered to be another name for the Trojan Astyanax saved from the destruction of Troy. He is not considered to be historical, but in fact an attempt by medieval and Renaissance chroniclers to model the founding of France upon the same illustrious tradition as that used by Virgil in his Aeneid.

European science in the Middle Ages comprised the study of nature, mathematics and natural philosophy in medieval Europe. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the decline in knowledge of Greek, Christian Western Europe was cut off from an important source of ancient learning. Although a range of Christian clerics and scholars from Isidore and Bede to Jean Buridan and Nicole Oresme maintained the spirit of rational inquiry, Western Europe would see a period of scientific decline during the Early Middle Ages. However, by the time of the High Middle Ages, the region had rallied and was on its way to once more taking the lead in scientific discovery. Scholarship and scientific discoveries of the Late Middle Ages laid the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution of the Early Modern Period.

The pignora imperii were objects that were supposed to guarantee the continued imperium of Ancient Rome. One late source lists seven. The sacred tokens most commonly regarded as such were:

Alexander of Roes was the dean of St. Maria im Kapitol, Cologne, canon law jurist, and author on history and prophecy. He was a member of a patrician Cologne family and was a member of the social group in Rome headed by Cardinal Jacobus de Columna, to whom he dedicated Memoriale...

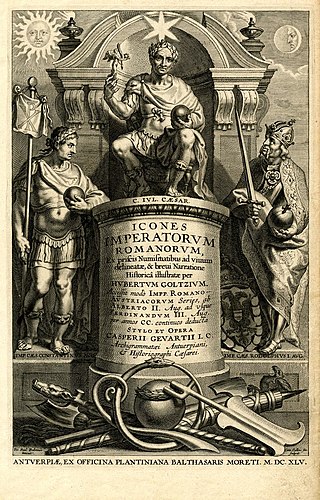

Icones Imperatorum Romanorum, originally published under the title Vivae omnium fere imperatorum imagines, is a 1557 originally Latin-language numismatic and historical work by the Dutch painter and engraver Hubert Goltzius. It was the first major work on the coins of the Roman emperors, featuring detailed portraits of each emperor from Julius Caesar to the then incumbent Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I based on their coins. The set of images, drawn by Goltzius himself and made into wood blocks by Joost Gietleugen van Kortrijk, is also accompanied by short biographies on each figure.