Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability or evidence of effectiveness. Unlike modern medicine, which employs the scientific method to test plausible therapies by way of responsible and ethical clinical trials, producing repeatable evidence of either effect or of no effect, alternative therapies reside outside of medical science and do not originate from using the scientific method, but instead rely on testimonials, anecdotes, religion, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural "energies", pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, or other unscientific sources. Frequently used terms for relevant practices are New Age medicine, pseudo-medicine, unorthodox medicine, holistic medicine, fringe medicine, and unconventional medicine, with little distinction from quackery.

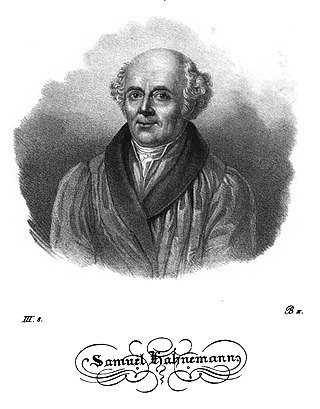

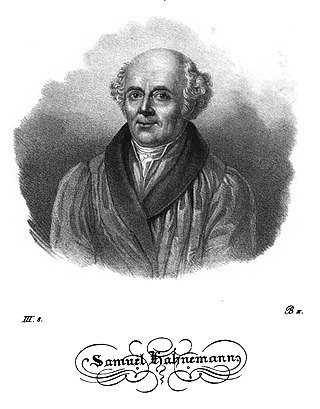

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a disease in healthy people can cure similar symptoms in sick people; this doctrine is called similia similibus curentur, or "like cures like". Homeopathic preparations are termed remedies and are made using homeopathic dilution. In this process, the selected substance is repeatedly diluted until the final product is chemically indistinguishable from the diluent. Often not even a single molecule of the original substance can be expected to remain in the product. Between each dilution homeopaths may hit and/or shake the product, claiming this makes the diluent "remember" the original substance after its removal. Practitioners claim that such preparations, upon oral intake, can treat or cure disease.

A placebo can be roughly defined as a sham medical treatment. Common placebos include inert tablets, inert injections, sham surgery, and other procedures.

A randomized controlled trial is a form of scientific experiment used to control factors not under direct experimental control. Examples of RCTs are clinical trials that compare the effects of drugs, surgical techniques, medical devices, diagnostic procedures, diets or other medical treatments.

Statins are a class of medications that reduce illness and mortality in people who are at high risk of cardiovascular disease. They are the most commonly prescribed cholesterol-lowering drugs, and are also known as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors.

In a blind or blinded experiment, information which may influence the participants of the experiment is withheld until after the experiment is complete. Good blinding can reduce or eliminate experimental biases that arise from a participants' expectations, observer's effect on the participants, observer bias, confirmation bias, and other sources. A blind can be imposed on any participant of an experiment, including subjects, researchers, technicians, data analysts, and evaluators. In some cases, while blinding would be useful, it is impossible or unethical. For example, it is not possible to blind a patient to their treatment in a physical therapy intervention. A good clinical protocol ensures that blinding is as effective as possible within ethical and practical constraints.

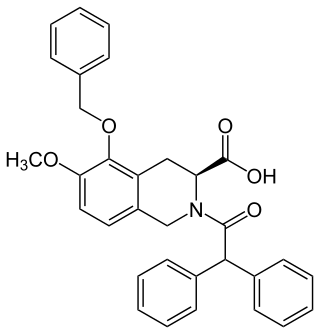

Duloxetine, sold under the brand name Cymbalta among others, is a medication used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain and central sensitization. It is taken by mouth.

Atorvastatin is a statin medication used to prevent cardiovascular disease in those at high risk and to treat abnormal lipid levels. For the prevention of cardiovascular disease, statins are a first-line treatment. It is taken by mouth.

A nocebo effect is said to occur when negative expectations of the patient regarding a treatment cause the treatment to have a more negative effect than it otherwise would have. For example, when a patient anticipates a side effect of a medication, they can experience that effect even if the "medication" is actually an inert substance. The complementary concept, the placebo effect, is said to occur when positive expectations improve an outcome. The nocebo effect is also said to occur in someone who falls ill owing to the erroneous belief that they were exposed to a toxin, e.g. a physical phenomenon they believe is harmful, such as EM radiation.

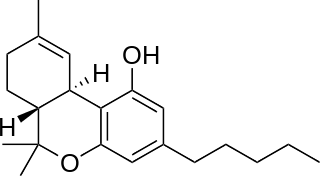

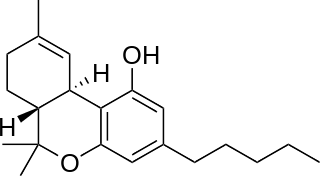

Nabiximols is a specific Cannabis extract that was approved in 2010 as a botanical drug in the United Kingdom. Nabiximols is sold as a mouth spray intended to alleviate neuropathic pain, spasticity, overactive bladder, and other symptoms of multiple sclerosis; it was developed by the UK company GW Pharmaceuticals. In 2019, it was proposed that following application of the spray, nabiximols is washed away from the oral mucosa by the saliva flow and ingested into the stomach, with subsequent absorption from the gastro-intestinal tract. Nabiximols is a combination drug standardized in composition, formulation, and dose. Its principal active components are the cannabinoids: tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Each spray delivers a dose of 2.7 mg THC and 2.5 mg CBD.

Agomelatine, sold under the brand names Valdoxan and Thymanax, among others, is an atypical antidepressant most commonly used to treat major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. One review found that it is as effective as other antidepressants with similar discontinuation rates overall but fewer discontinuations due to side effects. Another review also found it was similarly effective to many other antidepressants.

Henry Knowles Beecher was a pioneering American anesthesiologist, medical ethicist, and investigator of the placebo effect at Harvard Medical School.

Perindopril is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, or stable coronary artery disease.

Ted Jack Kaptchuk is an American medical researcher who holds professorships in medicine and in global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School. He researches the placebo effect within the field of placebo studies.

Peter Christian Gøtzsche is a Danish physician, medical researcher, and former leader of the Nordic Cochrane Center at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark. He is a co-founder of the Cochrane Collaboration and has written numerous reviews for the organization. His membership in Cochrane was terminated by its Governing Board of Trustees on 25 September 2018. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gøtzsche was criticised for spreading disinformation about COVID-19 vaccines.

Placebo-controlled studies are a way of testing a medical therapy in which, in addition to a group of subjects that receives the treatment to be evaluated, a separate control group receives a sham "placebo" treatment which is specifically designed to have no real effect. Placebos are most commonly used in blinded trials, where subjects do not know whether they are receiving real or placebo treatment. Often, there is also a further "natural history" group that does not receive any treatment at all.

The philosophy of medicine is a branch of philosophy that explores issues in theory, research, and practice within the field of health sciences. More specifically in topics of epistemology, metaphysics, and medical ethics, which overlaps with bioethics. Philosophy and medicine, both beginning with the ancient Greeks, have had a long history of overlapping ideas. It was not until the nineteenth century that the professionalization of the philosophy of medicine came to be. In the late twentieth century, debates among philosophers and physicians ensued of whether the philosophy of medicine should be considered a field of its own from either philosophy or medicine. A consensus has since been reached that it is in fact a distinct discipline with its set of separate problems and questions. In recent years there have been a variety of university courses, journals, books, textbooks and conferences dedicated to the philosophy of medicine.

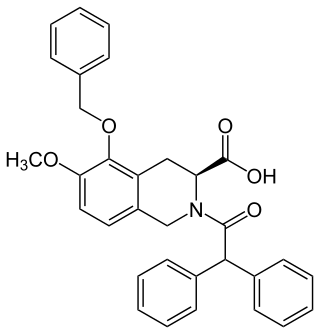

EMA401 is a drug under development for the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain. Trials were discontinued in 2015, with new trials scheduled to begin March, 2018. It was initially established as a potential drug option for patients suffering pain caused by postherpetic neuralgia. It may also be useful for treating various types of chronic neuropathic pain EMA401 has shown efficacy in preclinical models of shingles, diabetes, osteoarthritis, HIV and chemotherapy. EMA401 is a competitive antagonist of angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R) being developed by the Australian biotechnology company Spinifex Pharmaceuticals. EMA401 target angiotensin II type 2 receptors, which may have importance for painful sensitisation.

Jeremy Howick is a Canadian-born, British residing clinical epidemiologist and philosopher of science. He researches evidence-based medicine, clinical empathy and the philosophy of medicine, including the use of placebos in clinical practice and clinical trials. He is the author of over 100 peer-reviewed papers, as well as two books, The Philosophy of Evidence-Based Medicine in 2011, and Doctor You in 2017. In 2016, he received the Dawkins & Strutt grant from the British Medical Association to study pain treatment. He publishes in Philosophy of Medicine and medical journals. He is a member of the Sigma Xi research honours society.

The infinitesimally low concentration of homeopathic preparations, which often lack even a single molecule of the diluted substance, has been the basis of questions about the effects of the preparations since the 19th century. Modern advocates of homeopathy have proposed a concept of "water memory", according to which water "remembers" the substances mixed in it, and transmits the effect of those substances when consumed. This concept is inconsistent with the current understanding of matter, and water memory has never been demonstrated to exist, in terms of any detectable effect, biological or otherwise.