Civic Platform is a centre-right liberal political party in Poland. Since 2021, it is led by Donald Tusk, who previously led it from 2003–2014 and former president of the European Council from 2014–2019.

Neoliberalism, also neo-liberalism, is a term used to signify the late-20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent factor in the rise of conservative and right-libertarian organizations, political parties, and think tanks, and predominantly advocated by them, it is generally associated with policies of economic liberalization, including privatization, deregulation, globalization, free trade, monetarism, austerity, and reductions in government spending in order to increase the role of the private sector in the economy and society. The neoliberal project is also focused on designing institutions and has a political dimension. The defining features of neoliberalism in both thought and practice have been the subject of substantial scholarly debate.

Populism is a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group with "the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed in the late 19th century and has been applied to various politicians, parties and movements since that time, often as a pejorative. Within political science and other social sciences, several different definitions of populism have been employed, with some scholars proposing that the term be rejected altogether.

Political polarization is the divergence of political attitudes away from the center, towards ideological extremes.

Majoritarianism is a political philosophy or ideology with the agenda asserting that a majority based on a religion, language, social class, or other category of the population, is entitled to a certain degree of primacy in society, and has the right to make decisions that affect the society. This traditional view has come under growing criticism, and liberal democracies have increasingly included constraints on what the parliamentary majority can do, in order to protect citizens' fundamental rights.

An illiberal democracy describes a governing system that hides its "nondemocratic practices behind formally democratic institutions and procedures". There is a lack of consensus among experts about the exact definition of illiberal democracy or whether it even exists.

Sovereigntism, sovereignism or souverainism is the notion of having control over one's conditions of existence, whether at the level of the self, social group, region, nation or globe. Typically used for describing the acquiring or preserving political independence of a nation or a region, a sovereigntist aims to "take back control" from perceived powerful forces, either against internal subversive minority groups, or from external global governance institutions, federalism and supranational unions. It generally leans instead toward isolationism, and can be associated with certain independence movements, but has also been used to justify violating the independence of other nations.

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking to or for the "common people". Recurring themes of right-wing populists include neo-nationalism, social conservatism, economic nationalism and fiscal conservatism. Frequently, they aim to defend a national culture, identity, and economy against perceived attacks by outsiders. Right-wing populism has remained the dominant political force in the Republican Party in the United States since the 2010s.

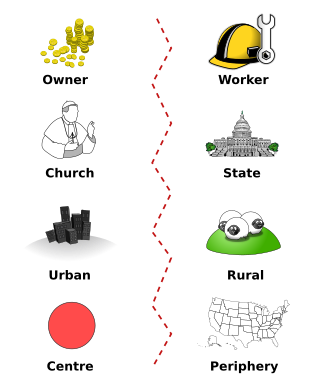

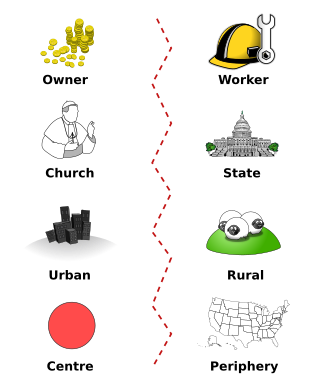

In political science and sociology, a cleavage is a historically determined social or cultural line which divides citizens within a society into groups with differing political interests, resulting in political conflict among these groups. Social or cultural cleavages thus become political cleavages once they get politicized as such. Cleavage theory accordingly argues that political cleavages predominantly determine a country's party system as well as the individual voting behavior of citizens, dividing them into voting blocs. It is distinct from other common political theories on voting behavior in the sense that it focuses on aggregate and structural patterns instead of individual voting behaviors.

Liberal democracy, substantive democracy, or western democracy is a form of government that combines the structure of a representative democracy with the principles of liberal political philosophy. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, a market economy with private property, universal suffrage, and the equal protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties, and political freedoms for all people. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either codified or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. The purpose of a constitution is often seen as a limit on the authority of the government.

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition; some scholars consider it to represent the left of social democracy, while others limit it to the left of communist parties. In certain instances—especially in the news media—far left has been associated with some forms of authoritarianism, anarchism, communism, and Marxism, or are characterized as groups that advocate for revolutionary socialism and related communist ideologies, or anti-capitalism and anti-globalization. Far-left terrorism consists of extremist, militant, or insurgent groups that attempt to realize their ideals through political violence rather than using democratic processes.

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often consists of anti-elitism, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking for the "common people". Recurring themes for left-wing populists include economic democracy, social justice, and scepticism of globalization. Socialist theory plays a lesser role than in traditional left-wing ideologies.

Post-politics refers to the critique of the emergence, in the post-Cold War period, of a politics of consensus on a global scale: the dissolution of the Eastern Communist bloc following the collapse of the Berlin Wall instituted a promise for post-ideological consensus. The political development in post-communist countries went two different directions depending on the approach each of them take on dealing with the communist party members. Active decommunisation process took place in Eastern European states which later joined EU. While in Russia and majority of former USSR republics communists became one of many political parties on equal grounds.

Tanja A. Börzel is a German political scientist. Her research and teaching focus on the fields of European Integration, Governance, and Diffusion. She is professor of Political Science at the Otto-Suhr-Institute of Political Science of Freie Universität Berlin, director of the Center for European Integration, and holder of the Jean Monnet Chair for European Integration from 2006 until 2009. Currently, she is department chair of the Otto-Suhr-Institute of Political Science.

Anti-politics is a term used to describe opposition to, or distrust in, traditional politics. It is closely connected with anti-establishment sentiment and public disengagement from formal politics. Anti-politics can indicate practices and actors that seek to remove political contestation from the public arena, leading to political apathy among citizens; when used this way the term is similar to depoliticisation. Alternatively, if politics is understood as encompassing all social institutions and power relations, anti-politics can mean political activity stemming from a rejection of "politics as usual".

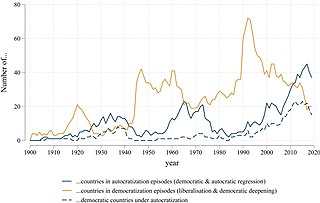

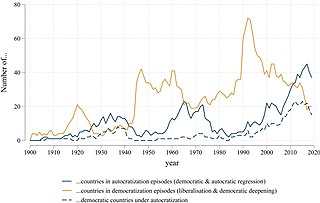

Democratic backsliding is a process of regime change towards autocracy that makes the exercise of political power by the public more arbitrary and repressive. This process typically restricts the space for public contestation and political participation in the process of government selection. Democratic decline involves the weakening of democratic institutions, such as the peaceful transition of power or free and fair elections, or the violation of individual rights that underpin democracies, especially freedom of expression.

Progressive Slovakia is a liberal and social-liberal political party in Slovakia established in 2017. The party is led by Vice President of the European Parliament Michal Šimečka. It is a member of the Renew Europe group and is a full member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party. PS has three MEPs: Michal Šimečka, Martin Hojsík, and Michal Wiezik ; Wiezik left the EPP group and Spolu to join PS. Zuzana Čaputová, incumbent President of Slovakia, co-founder and former deputy leader of Progressive Slovakia who won the 2019 Slovak presidential election, was nominated by the party for the election, focusing her campaign on themes of anti-corruption, environmentalism and Pro-Europeanism. In the National Council, it was first represented by deputy Tomáš Valášek elected for For the People, which he left in 2021. In local politics, PS has a dominant position in Bratislava, cooperating with Team Bratislava and Freedom and Solidarity.

The Confederation Liberty and Independence, frequently shortened to just Confederation, is a far-right political alliance in Poland. It was initially founded in 2018 as a political coalition for the 2019 European Parliament election in Poland, although it was later expanded into a political party in order to circumvent the 8% vote threshold for coalitions to enter the national parliament. It won 11 seats in the Sejm after the 2019 Polish parliamentary election. Its candidate for the 2020 Polish presidential election was Krzysztof Bosak, who placed fourth among eleven candidates.

Techno-populism is either a populism in favor of technocracy or a populism concerning certain technology – usually information technology – or any populist ideology conversed using digital media. It can be employed by single politicians or whole political movements respectively. Neighboring terms used in a similar way are technocratic populism, technological populism and cyber-populism. Italy’s Five Star Movement and France’s La République En Marche! have been described as technopopulist political movements.

The anti-gender movement is an international movement that opposes what it refers to as "gender ideology", "gender theory" or "genderism", terms which cover a variety of issues and do not have a coherent definition. Members of the anti-gender movement primarily include those of the political right-wing and far right, such as right-wing populists, conservatives, and Christian fundamentalists. Anti-gender rhetoric has seen increasing circulation in trans-exclusionary radical feminist (TERF) discourse since 2016. Members of the anti-gender movement oppose some LGBT rights, some reproductive rights, government gender policies, gender equality, gender mainstreaming, and gender studies academic departments.