Sociology of religion is the study of the beliefs, practices and organizational forms of religion using the tools and methods of the discipline of sociology. This objective investigation may include the use both of quantitative methods and of qualitative approaches.

David Émile Durkheim was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, along with both Karl Marx and Max Weber.

In sociology, anomie is a social condition defined by an uprooting or breakdown of any moral values, standards or guidance for individuals to follow. Anomie is believed to possibly evolve from conflict of belief systems and causes breakdown of social bonds between an individual and the community. An example is alienation in a person that can progress into a dysfunctional inability to integrate within normative situations of their social world such as finding a job, achieving success in relationships, etc.

The sociology of knowledge is the study of the relationship between human thought, the social context within which it arises, and the effects that prevailing ideas have on societies. It is not a specialized area of sociology. Instead, it deals with broad fundamental questions about the extent and limits of social influences on individuals' lives and the social-cultural basis of our knowledge about the world. The sociology of knowledge has a subclass and a complement. Its subclass is sociology of scientific knowledge. Its complement is the sociology of ignorance.

In sociology, social facts are values, cultural norms, and social structures that transcend the individual and can exercise social control. The French sociologist Émile Durkheim defined the term, and argued that the discipline of sociology should be understood as the empirical study of social facts. For Durkheim, social facts "consist of manners of acting, thinking and feeling external to the individual, which are invested with a coercive power by virtue of which they exercise control over him."

Ritualization refers to the process by which a sequence of non-communicating actions or an event is invested with cultural, social or religious significance. This definition emphasizes the transformation of everyday actions into rituals that carry deeper meaning within a cultural or religious context. Rituals are symbolic, repetitive, and often prescribed activities that hold religious or cultural significance for a certain group of people. They serve various purposes: promoting social solidarity by expressing shared values, facilitating the transmission of cultural knowledge and regulating emotions.

Maurice Halbwachs was a French philosopher and sociologist known for developing the concept of collective memory. Halbwachs also contributed to the sociology of knowledge with his La Topographie Legendaire des Évangiles en Terre Sainte; study of the spatial infrastructure of the New Testament. (1951)

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning a posteriori facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience. Other ways of knowing, such as intuition, introspection, or religious faith, are rejected or considered meaningless.

Social movement theory is an interdisciplinary study within the social sciences that generally seeks to explain why social mobilization occurs, the forms under which it manifests, as well as potential social, cultural, political, and economic consequences, such as the creation and functioning of social movements.

Suicide: A Study in Sociology is an 1897 book written by French sociologist Émile Durkheim. It was the second methodological study of a social fact in the context of society. It is ostensibly a case study of suicide, a publication unique for its time that provided an example of what the sociological monograph should look like.

Collective identity or group identity is a shared sense of belonging to a group. This concept appears within a few social science fields. National identity is a simple example, though myriad groups exist which share a sense of identity. Like many social concepts or phenomena, it is constructed, not empirically defined. Its discussion within these fields is often highly academic and relates to academia itself, its history beginning in the 19th century.

Sociology of terrorism is a field of sociology that seeks to understand terrorism as a social phenomenon. The field defines terrorism, studies why it occurs and evaluates its impacts on society. The sociology of terrorism draws from the fields of political science, history, economics and psychology. The sociology of terrorism differs from critical terrorism studies, emphasizing the social conditions that enable terrorism. It also studies how individuals as well as states respond to such events.

Collective mental state is generally a literary or legal term, mostly used in sociology and philosophy, to refer to the condition of someone's being-state when around others. An assessment of a collective mental state includes a description of thought processes, memory, emotions, mood, cognitive state, and energy levels, including the meta overlay of interactions between individuals.

In sociology, dynamic density refers to the combination of two things: population density and the amount of social interaction within that population. Émile Durkheim used the term to explain why societies transition from simple to more complex forms, specifically in terms of the division of labor within that society. He suggested that it required both an increase in population and an increase in the frequency of social interaction to form more specialised occupations, which then leads to a new type of society. People in this new type of society are less independent and more reliant on each other and therefore develop what he called organic solidarity, where people no longer are bound by the same morality and sense of purpose. Critics suggest that it is not a testable hypothesis, and nor does it follow logically that dynamic density would cause this new type of solidarity, supposing it actually existed.

The Division of Labour in Society is the doctoral dissertation of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, published in 1893. It was influential in advancing sociological theories and thought, with ideas which in turn were influenced by Auguste Comte. Durkheim described how social order was maintained in societies based on two very different forms of solidarity – mechanical and organic – and the transition from more "primitive" societies to advanced industrial societies.

Collective wisdom, also called group wisdom and co-intelligence, is shared knowledge arrived at by individuals and groups.

The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, published by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim in 1912, is a book that analyzes religion as a social phenomenon. Durkheim attributes the development of religion to the emotional security attained through communal living. His study of totemic societies in Australia led to a conclusion that the animal or plant that each clan worshipped as a sacred power was in fact that society itself. Halfway through the text, Durkheim asks, "So if [the totem animal] is at once the symbol of the god and of the society, is that not because the god and the society are only one?"

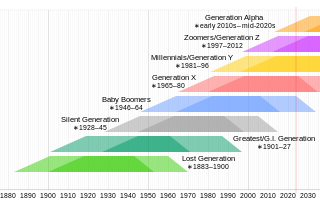

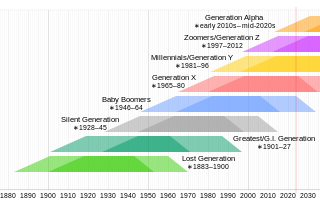

Theory of generations is a theory posed by Karl Mannheim in his 1928 essay, "Das Problem der Generationen," and translated into English in 1952 as "The Problem of Generations." This essay has been described as "the most systematic and fully developed" and even "the seminal theoretical treatment of generations as a sociological phenomenon". According to Mannheim, people are significantly influenced by the socio-historical environment of their youth; giving rise, on the basis of shared experience, to social cohorts that in their turn influence events that shape future generations. Because of the historical context in which Mannheim wrote, some critics contend that the theory of generations centers on Western ideas and lacks a broader cultural understanding. Others argue that the theory of generations should be global in scope, due to the increasingly globalized nature of contemporary society.

In sociology, mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity are the two types of social solidarity that were formulated by Émile Durkheim, introduced in his Division of Labour in Society (1893) as part of his theory on the development of societies. According to Durkheim, the type of solidarity will correlate with the type of society, either mechanical or organic society. The two types of solidarity can be distinguished by morphological and demographic features, type of norms in existence, and the intensity and content of the conscience collective.

Virtual collective consciousness (VCC) is a term rebooted and promoted by two behavioral scientists, Yousri Marzouki and Olivier Oullier in their 2012 Huffington Post article titled: “Revolutionizing Revolutions: Virtual Collective Consciousness and the Arab Spring”, after its first appearance in 1999-2000. VCC is now defined as an internal knowledge catalyzed by social media platforms and shared by a plurality of individuals driven by the spontaneity, the homogeneity, and the synchronicity of their online actions. VCC occurs when a large group of persons, brought together by a social media platform think and act with one mind and share collective emotions. Thus, they are able to coordinate their efforts efficiently, and could rapidly spread their word to a worldwide audience. When interviewed about the concept of VCC that appeared in the book - Hyperconnectivity and the Future of Internet Communication - he edited, Professor of Pervasive Computing, Adrian David Cheok mentioned the following: "The idea of a global (collective) virtual consciousness is a bottom-up process and a rather emergent property resulting from a momentum of complex interactions taking place in social networks. This kind of collective behaviour results from a collision between a physical world and a virtual world and can have a real impact in our life by driving collective action."