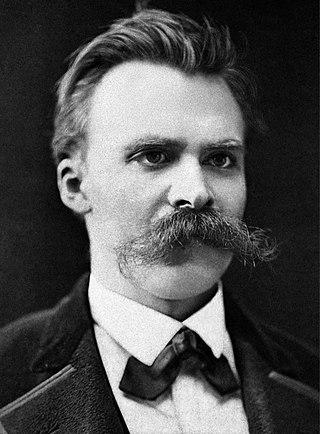

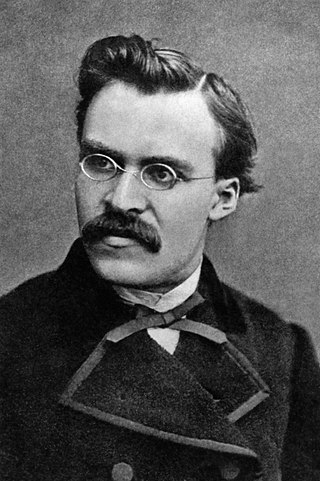

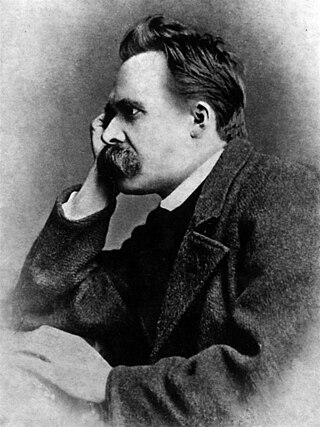

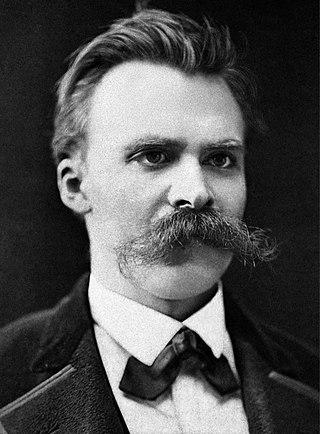

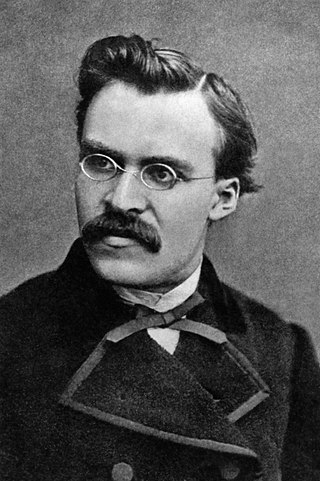

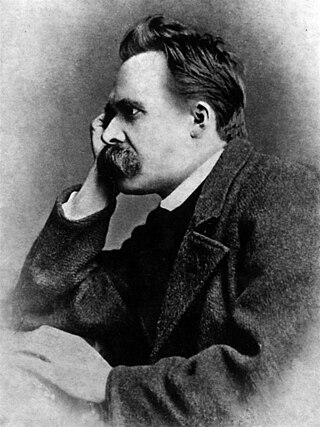

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24, but resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900, after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

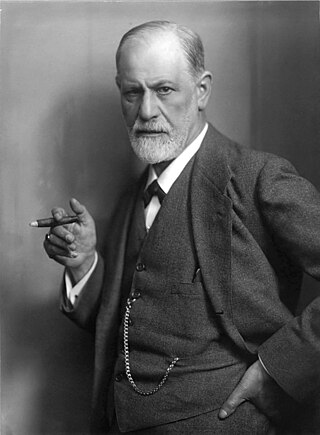

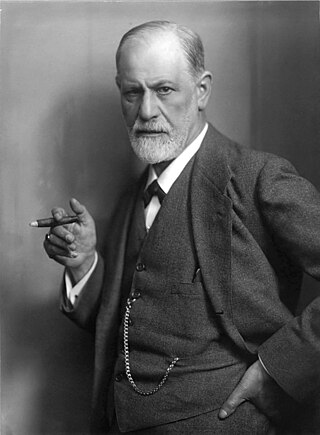

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Carl Gustav Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. He was a prolific author, illustrator, and correspondent, and a complex and controversial character, presumably best known through his "autobiography" Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

In psychoanalysis and other psychological theories, the unconscious mind is the part of the psyche that is not available to introspection. Although these processes exist beneath the surface of conscious awareness, they are thought to exert an effect on conscious thought processes and behavior. Empirical evidence suggests that unconscious phenomena include repressed feelings and desires, memories, automatic skills, subliminal perceptions, and automatic reactions. The term was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

"Rat Man" was the nickname given by Sigmund Freud to a patient whose "case history" was published as Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose ["Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis"] (1909). This was the second of six case histories that Freud published and the first in which he claimed that the patient had been cured by psychoanalysis.

Collective unconscious refers to the unconscious mind and shared mental concepts. It is generally associated with idealism and was coined by Carl Jung. According to Jung, the human collective unconscious is populated by instincts, as well as by archetypes: ancient primal symbols such as The Great Mother, the Wise Old Man, the Shadow, the Tower, Water, and the Tree of Life. Jung considered the collective unconscious to underpin and surround the unconscious mind, distinguishing it from the personal unconscious of Freudian psychoanalysis. He believed that the concept of the collective unconscious helps to explain why similar themes occur in mythologies around the world. He argued that the collective unconscious had a profound influence on the lives of individuals, who lived out its symbols and clothed them in meaning through their experiences. The psychotherapeutic practice of analytical psychology revolves around examining the patient's relationship to the collective unconscious.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, also translated as Thus Spake Zarathustra, is a work of philosophical fiction written by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche; it was published in four volumes between 1883 and 1885. The protagonist is nominally the historical Zoroaster.

Analytical psychology is a term coined by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, to describe research into his new "empirical science" of the psyche. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their seven-year collaboration on psychoanalysis was drawing to an end between 1912 and 1913. The evolution of his science is contained in his monumental opus, the Collected Works, written over sixty years of his lifetime.

In psychology, sublimation is a mature type of defense mechanism, in which socially unacceptable impulses or idealizations are transformed into socially acceptable actions or behavior, possibly resulting in a long-term conversion of the initial impulse.

A complex is a structure in the unconscious that is objectified as an underlying theme—like a power or a status—by grouping clusters of emotions, memories, perceptions and wishes in response to a threat to the stability of the self. In psychoanalysis, it is antithetical to drives.

The will to power is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's work, leaving its interpretation open to debate. Usage of the term by Nietzsche can be summarized as self-determination, the concept of actualizing one's will onto one's self or one's surroundings, and coincides heavily with egoism.

The expression immaculate perception, used by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in his text Thus Spoke Zarathustra; the term pertains to the idea of "pure knowledge." Nietzsche argues that "immaculate perception" is fictional because it ignores the intimate connection between the perceiver and the external world. He argues that humans are fallible and are capable of using data to ratify or refute perceptions. He also clarifies that perception is value-laden and can be ruled by our interests.

The Collected Worksof C. G. Jung is a book series containing the first collected edition, in English translation, of the major writings of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung.

Friedrich Nietzsche's influence and reception varied widely and may be roughly divided into various chronological periods. Reactions were anything but uniform, and proponents of various ideologies attempted to appropriate his work quite early.

A source-monitoring error is a type of memory error where the source of a memory is incorrectly attributed to some specific recollected experience. For example, individuals may learn about a current event from a friend, but later report having learned about it on the local news, thus reflecting an incorrect source attribution. This error occurs when normal perceptual and reflective processes are disrupted, either by limited encoding of source information or by disruption to the judgment processes used in source-monitoring. Depression, high stress levels and damage to relevant brain areas are examples of factors that can cause such disruption and hence source-monitoring errors.

"Peio Joxepe" is a traditional Navarrese song. It is very popular in the Basque Country, as its music is used by bertsolariak to improvise their compositions. Therefore, it may be sung with different lyrics.

The ideas of the 19th century German philosophers Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche have been compared frequently. Many authors have discussed apparent similarities in their writings, sometimes raising the question of influences. In Germany, during the early years of Nietzsche's emergence as a well-known figure, the only thinker who discussed his ideas more often than Stirner was Arthur Schopenhauer. It is certain that Nietzsche read about Stirner's book The Ego and Its Own, which was mentioned in Friedrich Albert Lange's History of Materialism and Critique of its Present Importance (1866) and Eduard von Hartmann's Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869), both of which young Nietzsche knew well. However, there is no irrefutable indication that he actually read it as no mention of Stirner is known to exist anywhere in Nietzsche's publications, papers or correspondence.

The relation between anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche has been ambiguous. Even though Nietzsche criticized anarchists, his thought proved influential for many of them. As such "[t]here were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'übermensch'—that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave".

In psychology, the misattribution of memory or source misattribution is the misidentification of the origin of a memory by the person making the memory recall. Misattribution is likely to occur when individuals are unable to monitor and control the influence of their attitudes, toward their judgments, at the time of retrieval. Misattribution is divided into three components: cryptomnesia, false memories, and source confusion. It was originally noted as one of Daniel Schacter's seven sins of memory.

Also sprach Zarathustra is the oil painting cycle by Lena Hades painted from 1995 to 1997 and inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophical novel of the same name. The painter created her first painting in December 1995 in Moscow. The Thus Spake Zarathustra cycle is a series of twenty-eight oil paintings made by the artist from 1995 to 1997 and thirty graphic works made in 2009. Twenty-four of the paintings depict so-called round-headed little men and their struggles in life. The remaining four depict Zarathustra himself, his eagle and serpent. Six paintings of the series were purchased by the Moscow Museum of Modern Art and by private collectors. The oil painting Also Sprach Zarathustra series was exhibited several times — including the exhibition at the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1997 and at the First Moscow Biennale of contemporary art in 2005.