Arousal and valence in memory

One of the most common frameworks in the emotions field proposes that affective experiences are best characterized by two main dimensions: arousal and valence. The dimension of valence ranges from highly positive to highly negative, whereas the dimension of arousal ranges from calming or soothing to exciting or agitating. [7] [8]

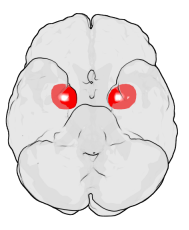

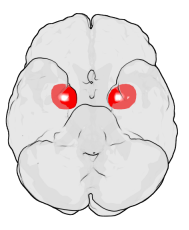

The majority of studies to date have focused on the arousal dimension of emotion as the critical factor contributing to the emotional enhancement effect on memory. [9] Different explanations have been offered for this effect, according to the different stages of memory formation and reconstruction. Memory has been shown to be better with arousal linked with emotion than without emotion. [10] The use of a PET scan has allowed scientists to see that pictures with an "emotional-stimulus" have significantly larger amount of activity in the amygdala. [11] In a study using fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG-PET) to examine the brain during recall of films that were both neutral and aversive, there was a positive correlation between the brain glucose and metabolic rate in the amygdala. [12] The activity in the amygalda is part of the episodic memory that was being created due to the adverse stimuli. [13]

However, a growing body of research is dedicated to the emotional valence dimension and its effects on memory. It has been claimed that this is an essential step towards a more complete understanding of emotion effects on memory. [14] The studies that did investigate this dimension have found that emotional valence alone can enhance memory; that is, nonarousing items with positive or negative valence can be better remembered than neutral items. [15] [16] [17]

Emotion and encoding

From an information processing perspective, encoding refers to the process of interpreting incoming stimuli and combining the processed information. At the encoding level the following mechanisms have been suggested as mediators of emotion effects on memory:

Selectivity of attention

Easterbrook's (1959) [18] cue utilization theory predicted that high levels of arousal will lead to attention narrowing, defined as a decrease in the range of cues from the stimulus and its environment to which the organism is sensitive. According to this hypothesis, attention will be focused primarily on the arousing details (cues) of the stimulus, so that information central to the source of the emotional arousal will be encoded while peripheral details will not. [19]

Accordingly, several studies have demonstrated that the presentation of emotionally-arousing stimuli (compared to neutral stimuli) results in enhanced memory for central details (details central to the appearance or meaning of the emotional stimuli) and impaired memory for peripheral details. [20] [21] Also consistent with this hypothesis are findings of weapon focus effect, [22] in which witnesses to a crime remember the gun or knife in great detail but not other details such as the perpetrator's clothing or vehicle. In laboratory replications it was found that participants spend a disproportionate amount of time looking at a weapon in a scene, and this looking time is inversely related to the likelihood that individuals will subsequently identify the perpetrator of the crime. [23] Other researchers have suggested arousal may also increase the duration of attentional focusing on the arousing stimuli, thus delaying the disengagement of attention from it. [24] Ochsner (2000) summarized the different findings and suggested that by influencing attention selectivity and dwell time, arousing stimuli are more distinctively encoded, resulting in more accurate memory of those stimuli. [15]

While these previous studies focused on how emotion affects memory for emotionally arousing stimuli, in their arousal-biased competition theory, Mather and Sutherland (2011) [25] argue that how arousal influences memory for non-emotional stimuli depends on the priority of those stimuli at the time of the arousal. Arousal enhances perception and memory of high priority stimuli but impairs perception and memory of low priority stimuli. Priority can be determined by bottom-up salience or by top-down goals.

Prioritized processing

Emotional items also appear more likely to be processed when attention is limited, suggesting a facilitated or prioritized processing of emotional information. [14] This effect was demonstrated using the attentional blink paradigm [26] in which 2 target items are presented in close temporal proximity within a stream of rapidly presented stimuli.

The typical finding is that participants often miss the second target item, as if there were a "blink" of attention following the first target's presentation, reducing the likelihood that the second target stimulus is attended. However, when the second target stimulus elicits emotional arousal (a "taboo" word), participants are less likely to miss the target's presentation, [27] which suggests that under conditions of limited attention, arousing items are more likely to be processed than neutral items.

Additional support for the prioritized processing hypothesis was provided by studies investigating the visual extinction deficit. People suffering from this deficit can perceive a single stimulus in either side visual field if it is presented alone but are unaware of the same stimulus in the visual field opposed to the lesional side, if another stimulus is presented simultaneously on the lesional side.

Emotion has been found to modulate the magnitude of the visual extinction deficit, so that items that signal emotional relevance (e.g., spiders) are more likely to be processed in the presence of competing distractors than nonemotional items (e.g., flowers). [28]

Emotion and storage

In addition to its effects during the encoding phase, emotional arousal appears to increase the likelihood of memory consolidation during the retention (storage) stage of memory (the process of creating a permanent record of the encoded information). A number of studies show that over time, memories for neutral stimuli decrease but memories for arousing stimuli remain the same or improve. [16] [29] [30]

Others have discovered that memory enhancements for emotional information tend to be greater after longer delays than after relatively short ones. [30] [31] [32] This delayed effect is consistent with the proposal that emotionally-arousing memories are more likely to be converted into a relatively permanent trace, whereas memories for nonarousing events are more vulnerable to disruption.

A few studies have even found that emotionally arousing stimuli enhance memory only after a delay. The most famous of these was a study by Kleinsmith and Kaplan (1963) [30] that found an advantage for numbers paired with arousing words over those paired with neutral words only at delayed test, but not at immediate test. As outlined by Mather (2007), [33] the Kleinsmith and Kaplan effects were most likely due to a methodological confound. However, Sharot and Phelps (2004) [19] found better recognition of arousing words over neutral words at a delayed test but not at an immediate test, supporting the notion that there is enhanced memory consolidation for arousing stimuli. [34] According to these theories, different physiological systems, including those involved in the discharge of hormones believed to affect memory consolidation, [35] [36] become active during, and closely following, the occurrence of arousing events.

Another possible explanation for the findings of the emotional arousal delayed effect is post-event processing regarding the cause of the arousal. According to the post stimulus elaboration (PSE) hypothesis, [5] an arousing emotional experience may cause more effort to be invested in elaboration of the experience, which would subsequently be processed at a deeper level than a neutral experience. Elaboration refers to the process of establishing links between newly-encountered information and previously-stored information.

It has long been known that when individuals process items in an elaborative fashion, such that meaning is extracted from items and inter-item associations are formed, memory is enhanced. [37] [38] Thus, if a person gives more thought to central details in an arousing event, memory for such information is likely to be enhanced. However, these processes could also disrupt consolidation of memories for peripheral details. Christianson (1992) suggested that the combined action of perceptual, attentional, and elaborative processing, triggered by an emotionally arousing experience, produces memory enhancements of details related to the emotion laden stimulus, at the cost of less elaboration and consolidation of memory for the peripheral details.

Emotion and elaboration

The processes involved in this enhancement may be distinct from those mediating the enhanced memory for arousing items. It has been suggested that in contrast to the relatively automatic attentional modulation of memory for arousing information, memory for non-arousing positive or negative stimuli may benefit instead from conscious encoding strategies, such as elaboration. [14] This elaborative processing can be autobiographical or semantic.

Autobiographical elaboration is known to benefit memory by creating links between the processed stimuli, and the self, for example, deciding whether a word would describe the personal self. Memory formed through autobiographical elaboration is enhanced as compared to items processed for meaning, but not in relation to the self. [39] [40]

Since words such as "sorrow" or "comfort" may be more likely to be associated with autobiographical experiences or self-introspection than neutral words such as "shadow", autobiographical elaboration may explain the memory enhancement of non-arousing positive or negative items. Studies have shown that dividing attention at encoding decreases an individual's ability to utilize controlled encoding processes, such as autobiographical or semantic elaboration.

Thus, findings that participants' memory for negative non-arousing words suffers with divided attention, [41] and that the memory advantage for negative, non-arousing words can be eliminated when participants encode items while simultaneously performing a secondary task, [42] has supported the elaborative processing hypothesis as the mechanism responsible for memory enhancement for negative non-arousing words.

Emotion and retrieval

Retrieval is a process of reconstructing past experiences; this phenomenon of reconstruction is influenced by a number of different variables described below.

Trade-off between details

Kensinger [43] argues there are two trade-offs: central/peripheral trade-off of details and a specific/general trade-off. Emotional memories may include increased emotional details often with the trade-off of excluding background information. Research has shown that this trade-off effect cannot be explained exclusively by overt attention (measured by eye-tracking directed to emotional items during encoding) (Steinmetz & Kensinger, 2013).

Contextual effects of emotion on memory

Contextual effects occur as a result of the degree of similarity between the encoding context and the retrieval context of an emotional dimension. The main findings are that the current mood we are in affects what is attended, encoded and ultimately retrieved, as reflected in two similar but subtly different effects: the mood congruence effect and mood-state dependent retrieval. Positive encoding contexts have been connected to activity in the right fusiform gyrus. Negative encoding contexts have been correlated to activity in the right amygdala (Lewis & Critchley, 2003). However, Lewis and Critchley (2003) claim that it is not clear whether involvement of the emotional system in encoding memory differs for positive or negative emotions, or whether moods at recall lead to activity in the corresponding positive or negative neural networks.

Mood congruence effect

The mood congruence effect refers to the tendency of individuals to retrieve information more easily when it has the same emotional content as their current emotional state. For instance, being in a depressed mood increases the tendency to remember negative events (Drace, 2013).

This effect has been demonstrated for explicit retrieval [44] as well as implicit retrieval. [45]

Mood-state dependent retrieval

Another documented phenomenon is the mood-state dependent retrieval, a type of context-dependent memory. The retrieval of information is more effective when the emotional state at the time of retrieval is similar to the emotional state at the time of encoding.

Thus, the probability of remembering an event can be enhanced by evoking the emotional state experienced during its initial processing. These two phenomena, the mood congruity effect, and mood-state dependent retrieval, are similar to the context effects which have been traditionally observed in memory research. [46] It may also relate to the phenomena of state-dependent memory in neuropsychopharmacology.

When recalling a memory, if someone is recalling an event by themselves or within a group of people, the emotions that they remember may change as well recall of specific details. Individuals recall events with stronger negative emotions than when a group is recalling the same event. [47] Collaborative recall, as it can be referred to, causes strong emotions to fade. Emotional tone changes as well, with a difference of individual or collaborative recall so much that an individual will keep the tone of what was previously felt, but the group will have a more neutral tone. For example, if someone is recalling the negative experience of taking a difficult exam, then they will talk in a negative tone. However, when the group is recalling taking the exam, they will most likely recount it in a positive tone as the negative emotions and tones fade. Detail recount is also something that changed based on the emotion state a person is in when they are remembering an event. If an event is being collaboratively recalled the specific detail count is higher than if an individual is doing it. [47] Detail recall is also more accurate when someone is experiencing negative emotion; Xie and Zhang (2016) [48] conducted a study in which participants saw a screen with five colors on it and when presented with the next screen were asked which color was missing. Those who were experiencing negative emotions were more precise than those in the positive and neutral conditions. Aside from emotional state, mental illness like depression relates to people's ability to recall specific details. [49] Those who are depressed tend to overgeneralize their memories and are not able to remember as many specific details of any events as compared to those without depression.

Thematic vs. sudden appearance of emotional stimuli

A somewhat different contextual effect stemmed from the recently made distinction between thematical and sudden appearance of an emotionally arousing event, suggesting that the occurrence of memory impairments depends on the way the emotional stimuli are induced. Laney et al. (2003) [50] argued that when arousal is induced thematically (i.e., not through the sudden appearance of a discrete shocking stimulus such as a weapon but rather through involvement in an unfolding event plot and empathy with the victim as his or her plight becomes increasingly apparent), memory enhancements of details central to the emotional stimulus need not come at the expense of memory impairment of peripheral details.

Laney et al. (2004) [51] demonstrated this by using an audio narrative to give the presented slides either neutral or emotional meaning, instead of presenting shockingly salient visual stimuli. In one of the experiments, participants in both the neutral and emotional conditions viewed slides of a date scenario of a woman and man at a dinner date. The couple engaged in conversation, then, at the end of the evening, embraced. The event concluded with the man leaving and the woman phoning a friend.

The accompanying audio recording informed participants in the neutral condition that the date went reasonably well, while participants in the emotional condition heard that, as the evening wore on, the man displayed some increasingly unpleasant traits of a type that was derogatory to women, and the embrace at the end of the evening was described as an attempt to sexually assault the woman.

As expected, the results revealed that details central to the event were remembered more accurately when that event was emotional than when neutral, However, this was not at the expense of memory for peripheral (in this case, spatially peripheral or plot-irrelevant) details, which were also remembered more accurately when the event was emotional. [51] Based on these findings it has been suggested that the dual enhancing and impairing effects on memory are not an inevitable consequence of emotional arousal.

Memory of felt emotion

Many researchers use self-report measures of felt emotion as a manipulation check. This raises an interesting question and a possible methodological weakness: are people always accurate when they recall how they felt in the past? [52] Several findings suggest this is not the case. For instance, in a study of memory for emotions in supporters of former U.S. presidential candidate Ross Perot, supporters were asked to describe their initial emotional reactions after Perot's unexpected withdrawal in July 1992 and again after the presidential election that November. [53]

Between the two assessment periods, the views of many supporters changed dramatically as Perot re-entered the race in October and received nearly a fifth of the popular vote. The results showed that supporters recalled their past emotions as having been more consistent with their current appraisals of Perot than they actually were. [52]

Another study found that people's memories for how distressed they felt when they learned of the 9/11 terrorist attacks changed over time and moreover, were predicted by their current appraisals of the impact of the attacks (Levine et al., 2004). It appears that memories of past emotional responses are not always accurate, and can even be partially reconstructed based on their current appraisal of events. [52]

Studies have shown that as episodic memory becomes less accessible over time, the reliance on semantic memory to remember past emotions increases. In one study Levine et al. (2009) [54] primes of the cultural belief of women being more emotional than men had a greater effect on responses for older memories compared to new memories. The long-term recall of emotions was more in line with the primed opinions, showing that long-term recall of emotions was heavily influenced by current opinions.

Emotion regulation effects on memory

An interesting issue in the study of the emotion-memory relationship is whether our emotions are influenced by our behavioral reaction to them, and whether this reaction—in the form of expression or suppression of the emotion—might affect what we remember about an event. Researchers have begun to examine whether concealing feelings influences our ability to perform common cognitive tasks, such as forming memories, and found that the emotion regulation efforts do have cognitive consequences. In the seminal work on negative affect arousal and white noise, Seidner found support for the existence of a negative affect arousal mechanism through observations regarding the devaluation of speakers from other ethnic origins." [55]

In a study of Richards and Gross (1999) and Tiwari (2013), [56] [57] participants viewed slides of injured men that produced increases in negative emotions, while information concerning each man was presented orally with his slide. The participants were assigned to either an expressive suppression group (where they were asked to refrain from showing emotion while watching the slides) or to a control group (where they were not given regulatory instructions at all). As predicted by the researchers, suppressors showed significantly worse performance on a memory test for the orally presented information.

In another study, it was investigated whether expressive suppression (i.e., keeping one's emotions subdued) comes with a cognitive price. [58] They measured expressive suppression when it spontaneously occurred while watching a movie of surgeries. After the movie, memory was tested and was found to be worse with a higher usage of suppression. In a second study, another movie was shown of people arguing. Memory of the conversation was then measured. When gauging the magnitude of cognitive cost, expressive suppression was compared with self-distraction, which was described as simply not trying to think about something. It was concluded that experimentally-induced suppression was associated with worse memory.

There is evidence that emotion enhances memory but is more specific towards arousal and valence factors. [59] To test this theory, arousal and valence were assessed for over 2,820 words. Both negative and positive stimuli were remembered higher than neutral stimuli. Arousal also did not predict recognition memory. In this study, the importance of stimulus controls and experimental designs in research memory was highlighted. Arousal-related activities when affiliated with heightened heart rate (HR) stimulate prediction of memory enhancement. [60] It was hypothesized that tonic elevations in HR (meaning revitalization in HR) and phasic HR (meaning quick reaction) declaration to help the memory. Fifty-three men's heart rates were measured while looking at unpleasant, neutral, and pleasant pictures and their memory tested two days later. It was concluded that tonic elevations created more accurate memory recall.

Several related studies have reached similar results. It was demonstrated that the effects of expressive suppression on memory generalize to emotionally positive experiences [61] and to socially relevant contexts. [62]

One possible answer to the question "why does emotion suppression impair memory?" might lay in the self monitoring efforts invested in order to suppress emotion (thinking about the behavior one is trying to control). A recent study [63] found heightened self- monitoring efforts among suppressors relative to control participants.

That is, suppressors were more likely to report thinking about their behavior and the need to control it during a conversation. Increases in self-monitoring predicted decreases in memory for what was said, that is, people who reported thinking a lot about controlling their behavior had particularly impoverished memories. However, additional research is needed to confirm whether self-monitoring actually exerts a causal effect on memory [64]

The amygdala is a paired nuclear complex present in the cerebral hemispheres of vertebrates. It is considered part of the limbic system. In primates, it is located medially within the temporal lobes. It consists of many nuclei, each made up of further subnuclei. The subdivision most commonly made is into the basolateral, central, cortical, and medial nuclei together with the intercalated cell clusters. The amygdala has a primary role in the processing of memory, decision-making, and emotional responses. The amygdala was first identified and named by Karl Friedrich Burdach in 1822.

A flashbulb memory is a vivid, long-lasting memory about a surprising or shocking event that has happened in the past.

Arousal is the physiological and psychological state of being awoken or of sense organs stimulated to a point of perception. It involves activation of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) in the brain, which mediates wakefulness, the autonomic nervous system, and the endocrine system, leading to increased heart rate and blood pressure and a condition of sensory alertness, desire, mobility, and reactivity.

Explicit memory is one of the two main types of long-term human memory, the other of which is implicit memory. Explicit memory is the conscious, intentional recollection of factual information, previous experiences, and concepts. This type of memory is dependent upon three processes: acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. More analysis produce more elaborate and stronger memory than lower levels of processing. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace. There are three levels of processing in this model. Structural processing, or visual, is when we remember only the physical quality of the word E.g how the word is spelled and how letters look. Phonemic processing includes remembering the word by the way it sounds. E.G the word tall rhymes with fall. Lastly, we have semantic processing in which we encode the meaning of the word with another word that is similar or has similar meaning. Once the word is perceived, the brain allows for a deeper processing.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

Affect, in psychology, refers to the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. In psychology, "affect" refers to the experience of feeling or emotion. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive or negative. Affect is a fundamental aspect of human experience and plays a central role in many psychological theories and studies. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity. In psychology, the term "affect" is often used interchangeably with several related terms and concepts, though each term may have slightly different nuances. These terms encompass: emotion, feeling, mood, emotional state, sentiment, affective state, emotional response, affective reactivity, disposition. Researchers and psychologists may employ specific terms based on their focus and the context of their work.

Negative affectivity (NA), or negative affect, is a personality variable that involves the experience of negative emotions and poor self-concept. Negative affectivity subsumes a variety of negative emotions, including anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear, and nervousness. Low negative affectivity is characterized by frequent states of calmness and serenity, along with states of confidence, activeness, and great enthusiasm.

Autobiographical memory (AM) is a memory system consisting of episodes recollected from an individual's life, based on a combination of episodic and semantic memory. It is thus a type of explicit memory.

In psychology, context-dependent memory is the improved recall of specific episodes or information when the context present at encoding and retrieval are the same. In a simpler manner, "when events are represented in memory, contextual information is stored along with memory targets; the context can therefore cue memories containing that contextual information". One particularly common example of context-dependence at work occurs when an individual has lost an item in an unknown location. Typically, people try to systematically "retrace their steps" to determine all of the possible places where the item might be located. Based on the role that context plays in determining recall, it is not at all surprising that individuals often quite easily discover the lost item upon returning to the correct context. This concept is heavily related to the encoding specificity principle.

The neuroanatomy of memory encompasses a wide variety of anatomical structures in the brain.

The effects of stress on memory include interference with a person's capacity to encode memory and the ability to retrieve information. Stimuli, like stress, improved memory when it was related to learning the subject. During times of stress, the body reacts by secreting stress hormones into the bloodstream. Stress can cause acute and chronic changes in certain brain areas which can cause long-term damage. Over-secretion of stress hormones most frequently impairs long-term delayed recall memory, but can enhance short-term, immediate recall memory. This enhancement is particularly relative in emotional memory. In particular, the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are affected. One class of stress hormone responsible for negatively affecting long-term, delayed recall memory is the glucocorticoids (GCs), the most notable of which is cortisol. Glucocorticoids facilitate and impair the actions of stress in the brain memory process. Cortisol is a known biomarker for stress. Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus regulates the production of cortisol through negative feedback because it has many receptors that are sensitive to these stress hormones. However, an excess of cortisol can impair the ability of the hippocampus to both encode and recall memories. These stress hormones are also hindering the hippocampus from receiving enough energy by diverting glucose levels to surrounding muscles.

Memory supports and enables social interactions in a variety of ways. In order to engage in successful social interaction, people must be able to remember how they should interact with one another, whom they have interacted with previously, and what occurred during those interactions. There are a lot of brain processes and functions that go into the application and use of memory in social interactions, as well as psychological reasoning for its importance.

Mood dependence is the facilitation of memory when mood at retrieval is identical to the mood at encoding. When one encodes a memory, they not only record sensory data, they also store their mood and emotional states. An individual's present mood thus affects the memories that are most easily available to them, such that when they are in a good mood they recall good memories. The associative nature of memory also means that one tends to store happy memories in a linked set. Unlike mood-congruent memory, mood-dependent memory occurs when one's current mood resembles their mood at the time of memory storage, which helps to recall the memory. Thus, the likelihood of remembering an event is higher when encoding and recall moods match up. However, it seems that only authentic moods have the power to produce these mood-dependent effects.

Eyewitness memory is a person's episodic memory for a crime or other witnessed dramatic event. Eyewitness testimony is often relied upon in the judicial system. It can also refer to an individual's memory for a face, where they are required to remember the face of their perpetrator, for example. However, the accuracy of eyewitness memories is sometimes questioned because there are many factors that can act during encoding and retrieval of the witnessed event which may adversely affect the creation and maintenance of the memory for the event. Experts have found evidence to suggest that eyewitness memory is fallible.

Many experiments have been done to find out how the brain interprets stimuli and how animals develop fear responses. The emotion, fear, has been hard-wired into almost every individual, due to its vital role in the survival of the individual. Researchers have found that fear is established unconsciously and that the amygdala is involved with fear conditioning.

Emotion perception refers to the capacities and abilities of recognizing and identifying emotions in others, in addition to biological and physiological processes involved. Emotions are typically viewed as having three components: subjective experience, physical changes, and cognitive appraisal; emotion perception is the ability to make accurate decisions about another's subjective experience by interpreting their physical changes through sensory systems responsible for converting these observed changes into mental representations. The ability to perceive emotion is believed to be both innate and subject to environmental influence and is also a critical component in social interactions. How emotion is experienced and interpreted depends on how it is perceived. Likewise, how emotion is perceived is dependent on past experiences and interpretations. Emotion can be accurately perceived in humans. Emotions can be perceived visually, audibly, through smell and also through bodily sensations and this process is believed to be different from the perception of non-emotional material.

The neurocircuitry that underlies executive function processes and emotional and motivational processes are known to be distinct in the brain. However, there are brain regions that show overlap in function between the two cognitive systems. Brain regions that exist in both systems are interesting mainly for studies on how one system affects the other. Examples of such cross-modal functions are emotional regulation strategies such as emotional suppression and emotional reappraisal, the effect of mood on cognitive tasks, and the effect of emotional stimulation of cognitive tasks.

Elizabeth Kensinger is Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Boston College. She is known for her research on emotion and memory over the human lifespan. She is co-author of the book Why We Forget and How To Remember Better: The Science Behind Memory, published in 2023 by Oxford University Press, which provides an overview of the psychology and neuroscience of memory. She also is the author of the book Emotional Memory Across the Adult Lifespan, which describes the selectivity of memory, i.e., how events infused with personal significance and emotion are much more memorable than nonemotional events. This book provides an overview of research on the cognitive and neural mechanisms underlying the formation and retrieval of emotional memories. Kensinger is co-author of a third book How Does Emotion Affect Attention and Memory? Attentional Capture, Tunnel Memory, and the Implications for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Katherine Mickley Steinmetz, which highlights the roles of emotion in determining what people pay attention to and later remember.

In cognitive psychology, the affect-as-information hypothesis, or 'approach', is a model of evaluative processing, postulating that affective feelings provide a source of information about objects, tasks, and decision alternatives. A goal of this approach is to understand the extent of influence that affect has on cognitive functioning. It has been proposed that affect has two major dimensions, namely affective valence and affective arousal, and in this way is an embodied source of information. Affect is thought to impact three main cognitive functions: judgement, thought processing and memory. In a variety of scenarios, the influence of affect on these processes is thought to be mediated by its effects on attention. The approach is thought to account for a wide variety of behavioural phenomena in psychology.