Related Research Articles

Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definition. Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.

In psychology, a mood is an affective state. In contrast to emotions or feelings, moods are less specific, less intense and less likely to be provoked or instantiated by a particular stimulus or event. Moods are typically described as having either a positive or negative valence. In other words, people usually talk about being in a good mood or a bad mood. There are many different factors that influence mood, and these can lead to positive or negative effects on mood.

Job satisfaction, employee satisfaction or work satisfaction is a measure of workers' contentment with their job, whether they like the job or individual aspects or facets of jobs, such as nature of work or supervision. Job satisfaction can be measured in cognitive (evaluative), affective, and behavioral components. Researchers have also noted that job satisfaction measures vary in the extent to which they measure feelings about the job. or cognitions about the job.

Emotional labor is the process of managing feelings and expressions to fulfill the emotional requirements of a job. More specifically, workers are expected to regulate their personas during interactions with customers, co-workers, clients, and managers. This includes analysis and decision-making in terms of the expression of emotion, whether actually felt or not, as well as its opposite: the suppression of emotions that are felt but not expressed. This is done so as to produce a certain feeling in the customer or client that will allow the company or organization to succeed.

Social exchange theory is a sociological and psychological theory that studies the social behavior in the interaction of two parties that implement a cost-benefit analysis to determine risks and benefits. The theory also involves economic relationships—the cost-benefit analysis occurs when each party has goods that the other parties value. Social exchange theory suggests that these calculations occur in romantic relationships, friendships, professional relationships, and ephemeral relationships as simple as exchanging words with a customer at the cash register. Social exchange theory says that if the costs of the relationship are higher than the rewards, such as if a lot of effort or money were put into a relationship and not reciprocated, then the relationship may be terminated or abandoned.

Emotional contagion is a form of social contagion that involves the spontaneous spread of emotions and related behaviors. Such emotional convergence can happen from one person to another, or in a larger group. Emotions can be shared across individuals in many ways, both implicitly or explicitly. For instance, conscious reasoning, analysis, and imagination have all been found to contribute to the phenomenon. The behaviour has been found in humans, other primates, dogs, and chickens.

Affect, in psychology, refers to the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. In psychology, "affect" refers to the experience of feeling or emotion. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive or negative. Affect is a fundamental aspect of human experience and plays a central role in many psychological theories and studies. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity. In psychology, the term "affect" is often used interchangeably with several related terms and concepts, though each term may have slightly different nuances. These terms encompass: emotion, feeling, mood, emotional state, sentiment, affective state, emotional response, affective reactivity, disposition. Researchers and psychologists may employ specific terms based on their focus and the context of their work.

Affective events theory (AET) is an industrial and organizational psychology model developed by organizational psychologists Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano to explain how emotions and moods influence job performance and job satisfaction. The model explains the linkages between employees' internal influences and their reactions to incidents that occur in their work environment that affect their performance, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. The theory proposes that affective work behaviors are explained by employee mood and emotions, while cognitive-based behaviors are the best predictors of job satisfaction. The theory proposes that positive-inducing as well as negative-inducing emotional incidents at work are distinguishable and have a significant psychological impact upon workers' job satisfaction. This results in lasting internal and external affective reactions exhibited through job performance, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment.

Dispositional affect, similar to mood, is a personality trait or overall tendency to respond to situations in stable, predictable ways. This trait is expressed by the tendency to see things in a positive or negative way. People with high positive affectivity tend to perceive things through "pink lens" while people with high negative affectivity tend to perceive things through "black lens". The level of dispositional affect affects the sensations and behavior immediately and most of the time in unconscious ways, and its effect can be prolonged. Research shows that there is a correlation between dispositional affect and important aspects in psychology and social science, such as personality, culture, decision making, negotiation, psychological resilience, perception of career barriers, and coping with stressful life events. That is why this topic is important both in social psychology research and organizational psychology research.

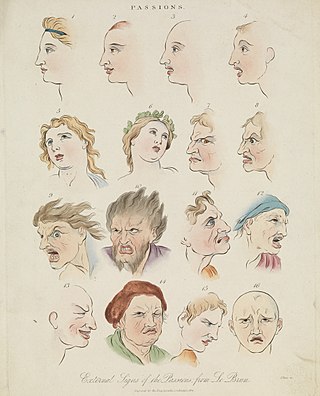

Affect displays are the verbal and non-verbal displays of affect (emotion). These displays can be through facial expressions, gestures and body language, volume and tone of voice, laughing, crying, etc. Affect displays can be altered or faked so one may appear one way, when they feel another. Affect can be conscious or non-conscious and can be discreet or obvious. The display of positive emotions, such as smiling, laughing, etc., is termed "positive affect", while the displays of more negative emotions, such as crying and tense gestures, is respectively termed "negative affect".

Emotional aperture has been defined as the ability to perceive features of group emotions. This skill involves the perceptual ability to adjust one's focus from a single individual's emotional cues to the broader patterns of shared emotional cues that comprise the emotional composition of the collective.

Emotional self-regulation or emotion regulation is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed. It can also be defined as extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions. Emotional self-regulation belongs to the broader set of emotion regulation processes, which includes both the regulation of one's own feelings and the regulation of other people's feelings.

Positive affectivity (PA) is a human characteristic that describes how much people experience positive affects ; and as a consequence how they interact with others and with their surroundings.

Negative affectivity (NA), or negative affect, is a personality variable that involves the experience of negative emotions and poor self-concept. Negative affectivity subsumes a variety of negative emotions, including anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, fear, and nervousness. Low negative affectivity is characterized by frequent states of calmness and serenity, along with states of confidence, activeness, and great enthusiasm.

Group affective tone represents the consistent or homogeneous affective reactions within a group.

Emotions in the workplace play a large role in how an entire organization communicates within itself and to the outside world. "Events at work have real emotional impact on participants. The consequences of emotional states in the workplace, both behaviors and attitudes, have substantial significance for individuals, groups, and society". "Positive emotions in the workplace help employees obtain favorable outcomes including achievement, job enrichment and higher quality social context". "Negative emotions, such as fear, anger, stress, hostility, sadness, and guilt, however increase the predictability of workplace deviance,", and how the outside world views the organization.

Limbic resonance is the idea that the capacity for sharing deep emotional states arises from the limbic system of the brain. These states include the dopamine circuit-promoted feelings of empathic harmony, and the norepinephrine circuit-originated emotional states of fear, anxiety and anger.

Interpersonal emotion regulation is the process of changing the emotional experience of one's self or another person through social interaction. It encompasses both intrinsic emotion regulation, in which one attempts to alter their own feelings by recruiting social resources, as well as extrinsic emotion regulation, in which one deliberately attempts to alter the trajectory of other people's feelings.

Emotional climate is a concept that quantifies the “climate” of a community, being a small group, a classroom, an organization, or a geographical region. It refers to the emotional relationships among members of a community and describes the overall emotional environment within a specific context.

Sigal G. Barsade was an Israeli-American business theorist and researcher, and was the Joseph Frank Bernstein Professor of Management at Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to research, she worked as a speaker and consultant to large corporations across a variety of industries, such as Coca-Cola, Deloitte, Google, IBM, KPMG and Merrill Lynch, healthcare organizations such as GlaxoSmithKline and Penn Medicine, and public and nonprofit corporations such as the World Economic Forum and the United Nations. At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Barsade co-chaired a task force of scholars aiming to utilize behavioral science to increase COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barsade S.G. & Gibson D.E. "Group Emotion: A View from Top and Bottom". Research on Managing Groups and Teams. 1: 81–102.

- ↑ Le Bon, G. (1896). The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (PDF). London, UK: Ernest Benn.

- ↑ Freud, S. (1922/1959). Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (trans. James Strachey). New York: W. W. Norton.

- ↑ Rafaeli, A. & Sutton, R. I. (1987). "The expression of emotion as part of the work role". Academy of Management Review. 12 (1): 23–37. doi:10.2307/257991. JSTOR 257991.

- ↑ Rafaeli, A. & Sutton, R. I. 1989. "The expression of emotion in organizational life". In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (eds.). Research in Organizational Behavior (PDF). Vol. 11. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. pp. 1–42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Kelly, J.R. & Barsade, S.G. (2001). "Mood and Emotions in Small Groups and Work Teams". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 86 (1): 99–130. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.724.4130 . doi:10.1006/obhd.2001.2974.

- ↑ Barsade, S.G.; Ward, A.J.; Turner, J.D.F.; Sonnenfeld, J.A. (2000). "To your heart's content: A model of affective diversity in top management teams" (PDF). Administrative Science Quarterly. 45 (4): 802–836. doi:10.2307/2667020. JSTOR 2667020. S2CID 144870339. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-16.

- ↑ A. Kramer; et al. (2014-06-17). "Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks". PNAS. 111 (24): 8788–8790. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.8788K. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320040111 . PMC 4066473 . PMID 24889601.

- ↑ E Ferrara & Z Yang (2015). "Measuring Emotional Contagion in Social Media". PLoS ONE . 10 (1): e0142390. arXiv: 1506.06021 . Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1042390F. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142390 . PMC 4636231 . PMID 26544688.

- ↑ Bartel C.A., Saavedra R. (2000). "The Collective Construction of Work Group Moods" (PDF). Administrative Science Quarterly. 45 (2): 197–231. doi:10.2307/2667070. JSTOR 2667070. S2CID 144568089. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-29.

- 1 2 Sy T.; Cote S.; Saavedra R. (2005). "The Contagious Leader: Impact of the Leader's Mood on the Mood of Group Members, Group Affective Tone, and Group Processes". Journal of Applied Psychology. 90 (2): 295–305. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295. PMID 15769239.

- ↑ Yang J. & Mossholder K.W. (2004). "Decoupling Task and Relationship Conflict: The Role of Intragroup Emotional Processing". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 25 (5): 589–605. doi:10.1002/job.258. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16.

- ↑ Barsade S.G. (2002). "The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and Its Influence on Group Behavior" (PDF). Administrative Science Quarterly. 47 (4): 644–675. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.4921 . doi:10.2307/3094912. JSTOR 3094912. S2CID 1397435. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007.

- ↑ Spoor J. R. & Kelly J. R. (2004). "The Evolutionary Significance of Affect in Groups: Communication and Group Bonding". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 7 (4): 398–412. doi:10.1177/1368430204046145. S2CID 143848904.

- ↑ Sanchez-Burks, J. & Huy, Q. (2008) "Emotional Aperture: The Accurate Recognition of Collective Emotions." Organization Science, pp. 1–13

- ↑ Sanchez-Burks, J. & Huy, Q. (2009). "Emotional Aperture: The Accurate Recognition of Collective Emotions". Organization Science. 20 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0347.

- ↑ Nisbett, R. E.; Peng, K.; Choi, I. & Norenzayan, A. (2001). "Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition" (PDF). Psychological Review. 108 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291. PMID 11381831. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-10. Retrieved 2016-04-29.