Related Research Articles

Aristotle was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science.

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and the nature of taste; and functions as the philosophy of art. Aesthetics examines the philosophy of aesthetic value, which is determined by critical judgements of artistic taste; thus, the function of aesthetics is the "critical reflection on art, culture and nature".

In ontology, the theory of categories concerns itself with the categories of being: the highest genera or kinds of entities according to Amie Thomasson. To investigate the categories of being, or simply categories, is to determine the most fundamental and the broadest classes of entities. A distinction between such categories, in making the categories or applying them, is called an ontological distinction. Various systems of categories have been proposed, they often include categories for substances, properties, relations, states of affairs or events. A representative question within the theory of categories might articulate itself, for example, in a query like, "Are universals prior to particulars?"

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiricism emphasizes the central role of empirical evidence in the formation of ideas, rather than innate ideas or traditions. Empiricists may argue that traditions arise due to relations of previous sensory experiences.

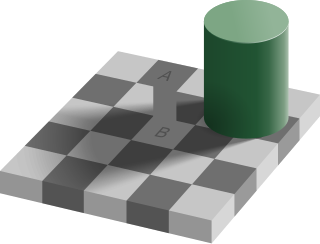

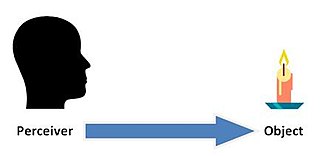

The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

Substance theory, or substance–attribute theory, is an ontological theory positing that objects are constituted each by a substance and properties borne by the substance but distinct from it. In this role, a substance can be referred to as a substratum or a thing-in-itself. Substances are particulars that are ontologically independent: they are able to exist all by themselves. Another defining feature often attributed to substances is their ability to undergo changes. Changes involve something existing before, during and after the change. They can be described in terms of a persisting substance gaining or losing properties. Attributes or properties, on the other hand, are entities that can be exemplified by substances. Properties characterize their bearers; they express what their bearer is like.

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality. In everyday language, truth is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences.

In common usage and in philosophy, ideas are the results of thought. Also in philosophy, ideas can also be mental representational images of some object. Many philosophers have considered ideas to be a fundamental ontological category of being. The capacity to create and understand the meaning of ideas is considered to be an essential and defining feature of human beings.

Edward Jonathan Lowe, usually cited as E. J. Lowe but known personally as Jonathan Lowe, was a British philosopher and academic. He was Professor of Philosophy at Durham University.

Subjective idealism, or empirical idealism or immaterialism, is a form of philosophical monism that holds that only minds and mental contents exist. It entails and is generally identified or associated with immaterialism, the doctrine that material things do not exist. Subjective idealism rejects dualism, neutral monism, and materialism; it is the contrary of eliminative materialism, the doctrine that all or some classes of mental phenomena do not exist, but are sheer illusions.

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

Essence has various meanings and uses for different thinkers and in different contexts. It is used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property or set of properties or attributes that make an entity the entity it is or, expressed negatively, without which it would lose its identity. Essence is contrasted with accident, which is a property or attribute the entity has accidentally or contingently, but upon which its identity does not depend.

In logic and philosophy, a property is a characteristic of an object; a red object is said to have the property of redness. The property may be considered a form of object in its own right, able to possess other properties. A property, however, differs from individual objects in that it may be instantiated, and often in more than one object. It differs from the logical/mathematical concept of class by not having any concept of extensionality, and from the philosophical concept of class in that a property is considered to be distinct from the objects which possess it. Understanding how different individual entities can in some sense have some of the same properties is the basis of the problem of universals.

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, are differing models that describe the nature of conscious experiences; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

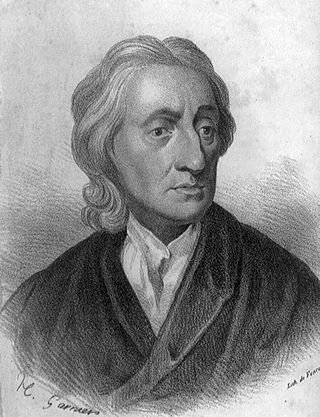

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 with the printed title An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. He describes the mind at birth as a blank slate filled later through experience. The essay was one of the principal sources of empiricism in modern philosophy, and influenced many enlightenment philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley.

The Categories is a text from Aristotle's Organon that enumerates all the possible kinds of things that can be the subject or the predicate of a proposition. They are "perhaps the single most heavily discussed of all Aristotelian notions". The work is brief enough to be divided not into books, as is usual with Aristotle's works, but into fifteen chapters.

In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in his Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, and De Anima.

Metaphysics is one of the principal works of Aristotle, in which he develops the doctrine that he calls First Philosophy. The work is a compilation of various texts treating abstract subjects, notably substance theory, different kinds of causation, form and matter, the existence of mathematical objects and the cosmos, which together constitute much of the branch of philosophy later known as metaphysics.

Corpuscularianism, also known as corpuscularism, is a set of theories that explain natural transformations as a result of the interaction of particles. It differs from atomism in that corpuscles are usually endowed with a property of their own and are further divisible, while atoms are neither. Although often associated with the emergence of early modern mechanical philosophy, and especially with the names of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, corpuscularian theories can be found throughout the history of Western philosophy.

The primary–secondary quality distinction is a conceptual distinction in epistemology and metaphysics, concerning the nature of reality. It is most explicitly articulated by John Locke in his Essay concerning Human Understanding, but earlier thinkers such as Galileo and Descartes made similar distinctions.

References

- 1 2 3 Cargile, J. (1995). qualities. in Honderich, T. (Ed.) (2005). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford

- ↑ Edghill, E.M. trans. (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive – Aristotle Categories". MIT. line 70.

- ↑ Edghill, E.M. trans. (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive – Aristotle Categories". MIT. line 254.

- ↑ Edghill, E.M. trans. (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive – Aristotle Categories". MIT. line 28.

- ↑ Taylor, Edwin F. and Wheeler, John Archibald, Spacetime Physics, 2nd edition, 1991, p. 195.

- ↑ Studtmann, P. (2007). Zalta, E.N. (ed.). "Aristotle's Categories". Stanford: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[Regarding] Habits and Dispositions; Natural Capabilities and Incapabilities; Affective Qualities and Affections; and Shapes; [...] Ackrill finds Aristotle's division of quality at best unmotivated.

- ↑ Reese, William L. (1996). Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-621-8.

- ↑ Lütke, Oliver (2020). Qualität und Kulturelles Kapital : Wie Haltungen das Ergebnis von Handlungen beeinflussen : Über Mitbestimmung und Kultur im Unternehmen, den Umgang mit Macht und die Auswirkungen. Berlin: Winter Industries GmbH – Verlag im Internet, 2020, 4th revised edition 2020. p. 373. ISBN 978-3-86624-637-9.