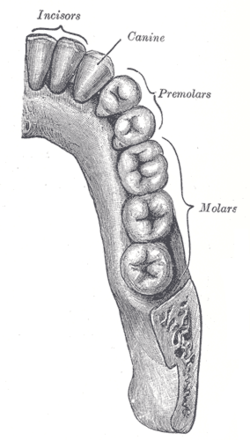

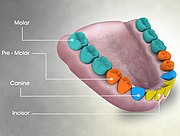

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or vampire fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. In the context of the upper jaw, they are also known as fangs. They can appear more flattened however, causing them to resemble incisors and leading them to be called incisiform. They developed and are used primarily for firmly holding food in order to tear it apart, and occasionally as weapons. They are often the largest teeth in a mammal's mouth. Individuals of most species that develop them normally have four, two in the upper jaw and two in the lower, separated within each jaw by incisors; humans and dogs are examples. In most species, canines are the anterior-most teeth in the maxillary bone. The four canines in humans are the two upper maxillary canines and the two lower mandibular canines. They are specially prominent in dogs (canidae), hence the name.

The maxillary central incisor is a human tooth in the front upper jaw, or maxilla, and is usually the most visible of all teeth in the mouth. It is located mesial to the maxillary lateral incisor. As with all incisors, their function is for shearing or cutting food during mastication (chewing). There is typically a single cusp on each tooth, called an incisal ridge or incisal edge. Formation of these teeth begins at 14 weeks in utero for the deciduous (baby) set and 3–4 months of age for the permanent set.

The maxillary first molar is the human tooth located laterally from both the maxillary second premolars of the mouth but mesial from both maxillary second molars.

The mandibular canine is the tooth located distally from both mandibular lateral incisors of the mouth but mesially from both mandibular first premolars. Both the maxillary and mandibular canines are called the "cornerstone" of the mouth because they are all located three teeth away from the midline, and separate the premolars from the incisors. The location of the canines reflect their dual function as they complement both the premolars and incisors during mastication, commonly known as chewing. Nonetheless, the most common action of the canines is tearing of food. The canine teeth are able to withstand the tremendous lateral pressures from chewing. There is a single cusp on canines, and they resemble the prehensile teeth found in carnivorous animals. Though relatively the same, there are some minor differences between the deciduous (baby) mandibular canine and that of the permanent mandibular canine.

The mandibular first premolar is the tooth located laterally from both the mandibular canines of the mouth but mesial from both mandibular second premolars. The function of this premolar is similar to that of canines in regard to tearing being the principal action during mastication, commonly known as chewing. Mandibular first premolars have two cusps. The one large and sharp is located on the buccal side of the tooth. Since the lingual cusp is small and nonfunctional, the mandibular first premolar resembles a small canine. There are no deciduous (baby) mandibular premolars. Instead, the teeth that precede the permanent mandibular premolars are the deciduous mandibular molars.

The mandibular second premolar is the tooth located distally from both the mandibular first premolars of the mouth but mesial from both mandibular first molars. The function of this premolar is assist the mandibular first molar during mastication, commonly known as chewing. Mandibular second premolars have three cusps. There is one large cusp on the buccal side of the tooth. The lingual cusps are well developed and functional. Therefore, whereas the mandibular first premolar resembles a small canine, the mandibular second premolar is more alike to the first molar. There are no deciduous (baby) mandibular premolars. Instead, the teeth that precede the permanent mandibular premolars are the deciduous mandibular molars.

The mandibular first molar or six-year molar is the tooth located distally from both the mandibular second premolars of the mouth but mesial from both mandibular second molars. It is located on the mandibular (lower) arch of the mouth, and generally opposes the maxillary (upper) first molars and the maxillary 2nd premolar in normal class I occlusion. The function of this molar is similar to that of all molars in regard to grinding being the principal action during mastication, commonly known as chewing. There are usually five well-developed cusps on mandibular first molars: two on the buccal, two lingual, and one distal. The shape of the developmental and supplementary grooves, on the occlusal surface, are described as being 'M' shaped. There are great differences between the deciduous (baby) mandibular molars and those of the permanent mandibular molars, even though their function are similar. The permanent mandibular molars are not considered to have any teeth that precede it. Despite being named molars, the deciduous molars are followed by permanent premolars.

Dens evaginatus is a rare odontogenic developmental anomaly that is found in teeth where the outer surface appears to form an extra bump or cusp.

Dental anatomy is a field of anatomy dedicated to the study of human tooth structures. The development, appearance, and classification of teeth fall within its purview. Tooth formation begins before birth, and the teeth's eventual morphology is dictated during this time. Dental anatomy is also a taxonomical science: it is concerned with the naming of teeth and the structures of which they are made, this information serving a practical purpose in dental treatment.

Occlusion, in a dental context, means simply the contact between teeth. More technically, it is the relationship between the maxillary (upper) and mandibular (lower) teeth when they approach each other, as occurs during chewing or at rest.

A cusp is a pointed, projecting, or elevated feature. In animals, it is usually used to refer to raised points on the crowns of teeth. The concept is also used with regard to the leaflets of the four heart valves. The mitral valve, which has two cusps, is also known as the bicuspid valve, and the tricuspid valve has three cusps.

This is a list of definitions of commonly used terms of location and direction in dentistry. This set of terms provides orientation within the oral cavity, much as anatomical terms of location provide orientation throughout the body.

Crossbite is a form of malocclusion where a tooth has a more buccal or lingual position than its corresponding antagonist tooth in the upper or lower dental arch. In other words, crossbite is a lateral misalignment of the dental arches.

Dental pertains to the teeth, including dentistry. Topics related to the dentistry, the human mouth and teeth include:

A lingual arch is an orthodontic device which connects two molars in the upper or lower dental arch. The lower lingual arch (LLA) has an archwire adapted to the lingual side of the lower teeth. In the upper arch the archwire is usually connecting the two molars passing through the palatal vault, and is commonly referred as "Transpalatal Arch" (TPA). The TPA was originally described by Robert Goshgarian in 1972. TPAs could possibly be used for maintaining transverse arch widths, anchorage in extraction case, prevent buccal tipping of molars during Burstonian segmented arch mechanics, transverse anchorage and space maintenance.

The Lewis offset is a term for the portion of the central groove on a permanent mandibular first molar which lies between the two central pits. It was named for long time dental anatomy instructor Dr. Christopher S. Lewis, a Mercer Island, WA dentist.

Serial extraction is the planned extraction of certain deciduous teeth and specific permanent teeth in an orderly sequence and predetermined pattern to guide the erupting permanent teeth into a more favorable position.

Intrusion is a movement in the field of orthodontics where a tooth is moved partially into the bone. Intrusion is done in orthodontics to correct an anterior deep bite or in some cases intrusion of the over-erupted posterior teeth with no opposing tooth. Intrusion can be done in many ways and consists of many different types. Intrusion, in orthodontic history, was initially defined as problematic in early 1900s and was known to cause periodontal effects such as root resorption and recession. However, in mid 1950s successful intrusion with light continuous forces was demonstrated. Charles J. Burstone defined intrusion to be "the apical movement of the geometric center of the root (centroid) in respect to the occlusal plane or plane based on the long axis of tooth".

An ectopic maxillary canine is a canine which is following abnormal path of eruption in the maxilla. An impacted tooth is one which is blocked from erupting by a physical barrier in the path of eruption. Ectopic eruption may lead to impaction. Previously, it was assumed that 85% of ectopic canines are displaced palatally, however a recent study suggests the true occurrence is closer to 50%. While maxillary canines can also be displaced buccally, it is thought this arises as a result of a lack of space. Most of these cases resolve themselves with the permanent canine erupting without intervention.

Orthodontic indices are one of the tools that are available for orthodontists to grade and assess malocclusion. Orthodontic indices can be useful for an epidemiologist to analyse prevalence and severity of malocclusion in any population.