Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social intervention that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most effective means of treatment for substance abuse and co-occurring mental health disorders. CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed to treat depression, its uses have been expanded to include many issues and the treatment of many mental health conditions, including anxiety, substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders. CBT includes a number of cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies that treat defined psychopathologies using evidence-based techniques and strategies.

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. Hypochondria is an old concept whose meaning has repeatedly changed over its lifespan. It has been claimed that this debilitating condition results from an inaccurate perception of the condition of body or mind despite the absence of an actual medical diagnosis. An individual with hypochondriasis is known as a hypochondriac. Hypochondriacs become unduly alarmed about any physical or psychological symptoms they detect, no matter how minor the symptom may be, and are convinced that they have, or are about to be diagnosed with, a serious illness.

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary medical caregiving approach aimed at optimizing quality of life and mitigating suffering among people with serious, complex, and often terminal illnesses. Within the published literature, many definitions of palliative care exist. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes palliative care as "an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual". In the past, palliative care was a disease specific approach, but today the WHO takes a broader patient-centered approach that suggests that the principles of palliative care should be applied as early as possible to any chronic and ultimately fatal illness. This shift was important because if a disease-oriented approach is followed, the needs and preferences of the patient are not fully met and aspects of care, such as pain, quality of life, and social support, as well as spiritual and emotional needs, fail to be addressed. Rather, a patient-centered model prioritizes relief of suffering and tailors care to increase the quality of life for terminally ill patients.

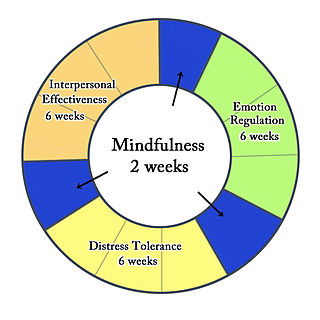

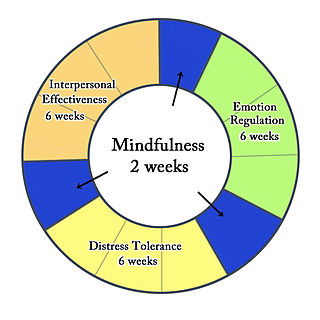

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

Pain disorder is chronic pain experienced by a patient in one or more areas, and is thought to be caused by psychological stress. The pain is often so severe that it disables the patient from proper functioning. Duration may be as short as a few days or as long as many years. The disorder may begin at any age, and occurs more frequently in girls than boys. This disorder often occurs after an accident, during an illness that has caused pain, or after withdrawing from use during drug addiction, which then takes on a 'life' of its own.

A cancer survivor is a person with cancer of any type who is still living. Whether a person becomes a survivor at the time of diagnosis or after completing treatment, whether people who are actively dying are considered survivors, and whether healthy friends and family members of the cancer patient are also considered survivors, varies from group to group. Some people who have been diagnosed with cancer reject the term survivor or disagree with some definitions of it.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms are symptoms for which a treating physician or other healthcare providers have found no medical cause, or whose cause remains contested. In its strictest sense, the term simply means that the cause for the symptoms is unknown or disputed—there is no scientific consensus. Not all medically unexplained symptoms are influenced by identifiable psychological factors. However, in practice, most physicians and authors who use the term consider that the symptoms most likely arise from psychological causes. Typically, the possibility that MUPS are caused by prescription drugs or other drugs is ignored. It is estimated that between 15% and 30% of all primary care consultations are for medically unexplained symptoms. A large Canadian community survey revealed that the most common medically unexplained symptoms are musculoskeletal pain, ear, nose, and throat symptoms, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and dizziness. The term MUPS can also be used to refer to syndromes whose etiology remains contested, including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivity and Gulf War illness.

Exposure therapy is a technique in behavior therapy to treat anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy involves exposing the target patient to the anxiety source or its context without the intention to cause any danger (desensitization). Doing so is thought to help them overcome their anxiety or distress. Procedurally, it is similar to the fear extinction paradigm developed for studying laboratory rodents. Numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in the treatment of disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and specific phobias.

Mixed anxiety–depressive disorder (MADD) is a diagnostic category defining patients who have both anxiety and depressive symptoms of limited and equal intensity accompanied by at least some autonomic features. Autonomic features are involuntary physical symptoms usually caused by an overactive nervous system, such as panic attacks or intestinal distress. The World Health Organization's ICD-10 describes Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder: "...when symptoms of anxiety and depression are both present, but neither is clearly predominant, and neither type of symptom is present to the extent that justifies a diagnosis if considered separately. When both anxiety and depressive symptoms are present and severe enough to justify individual diagnoses, both diagnoses should be recorded and this category should not be used."

Functional disorder is an umbrella term for a group of recognisable medical conditions which are due to changes to the functioning of the systems of the body rather than due to a disease affecting the structure of the body.

An informal or primary caregiver is an individual in a cancer patient's life that provides unpaid assistance and cancer-related care. Due to the typically late onset of cancer, caregivers are often the spouses and/or children of patients, but may also be parents, other family members, or close friends. Informal caregivers are a major form of support for the cancer patient because they provide most care outside of the hospital environment. This support includes:

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is an eight-week evidence-based program that offers secular, intensive mindfulness training to assist people with stress, anxiety, depression and pain. Developed at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in the 1970s by Professor Jon Kabat-Zinn, MBSR uses a combination of mindfulness meditation, body awareness, yoga and exploration of patterns of behaviour, thinking, feeling and action. Mindfulness can be understood as the non-judgmental acceptance and investigation of present experience, including body sensations, internal mental states, thoughts, emotions, impulses and memories, in order to reduce suffering or distress and to increase well-being. Mindfulness meditation is a method by which attention skills are cultivated, emotional regulation is developed, and rumination and worry are significantly reduced. During the past decades, mindfulness meditation has been the subject of more controlled clinical research, which suggests its potential beneficial effects for mental health, as well as physical health. While MBSR has its roots in wisdom teachings of Zen Buddhism, Hatha Yoga, Vipassana and Advaita Vedanta, the program itself is secular. The MBSR program is described in detail in Kabat-Zinn's 1990 book Full Catastrophe Living.

Cancer-related fatigue is a symptom of fatigue that is experienced by nearly all cancer patients.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a technique for treating insomnia without medications. Insomnia is a common problem involving trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting quality sleep. CBT-I aims to improve sleep habits and behaviors by identifying and changing the thoughts and the behaviors that affect the ability of a person to sleep or sleep well.

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder, is defined by one or more chronic physical symptoms that coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symptoms. The symptoms are not purposefully produced or feigned, and they may or may not coexist with a known medical ailment.

Pediatric psychology is a multidisciplinary field of both scientific research and clinical practice which attempts to address the psychological aspects of illness, injury, and the promotion of health behaviors in children, adolescents, and families in a pediatric health setting. Psychological issues are addressed in a developmental framework and emphasize the dynamic relationships which exist between children, their families, and the health delivery system as a whole.

Linda E. Carlson is a Canadian clinical psychologist. She is a professor at the University of Calgary, where she holds the Enbridge Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology.

Margaret Ruth McCorkle FAAN, FAPOS was an American nurse, oncology researcher, and educator. She was the Florence Schorske Wald Professor of Nursing at the Yale School of Nursing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of people across the globe. The pandemic has caused widespread anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. According to the UN health agency WHO, in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, prevalence of common mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, went up by more than 25 percent. The pandemic has damaged social relationships, trust in institutions and in other people, has caused changes in work and income, and has imposed a substantial burden of anxiety and worry on the population. Women and young people face the greatest risk of depression and anxiety.

Psychosocial distress refers to the unpleasant emotions or psychological symptoms an individual has when they are overwhelmed, which negatively impacts their quality of life. Psychosocial distress is most commonly used in medical care to refer to the emotional distress experienced by populations of patients and caregivers of patients with complex chronic conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions, which confer heavy symptom burdens that are often overwhelming, due to the disease's association with death. Due to the significant history of psychosocial distress in cancer treatment, and a lack of reliable secondary resources documenting distress in other contexts, psychosocial distress will be mainly discussed in the context of oncology.