Perl is a high-level, general-purpose, interpreted, dynamic programming language. Though Perl is not officially an acronym, there are various backronyms in use, including "Practical Extraction and Reporting Language".

Parrot is a discontinued register-based process virtual machine designed to run dynamic languages efficiently. It is possible to compile Parrot assembly language and Parrot intermediate representation to Parrot bytecode and execute it. Parrot is free and open-source software.

Programming languages can be grouped by the number and types of paradigms supported.

D, also known as dlang, is a multi-paradigm system programming language created by Walter Bright at Digital Mars and released in 2001. Andrei Alexandrescu joined the design and development effort in 2007. Though it originated as a re-engineering of C++, D is now a very different language drawing inspiration from other high-level programming languages, notably Java, Python, Ruby, C#, and Eiffel.

Plain Old Documentation (pod) is a lightweight markup language used to document the Perl programming language as well as Perl modules and programs.

Pugs is a compiler and interpreter for the Raku programming language, started on February 1, 2005, by Audrey Tang.

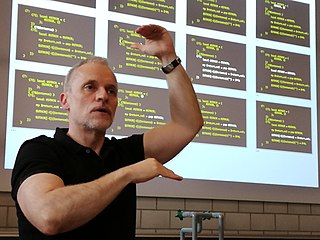

Damian Conway is a computer scientist, a member of the Perl and Raku communities, a public speaker, and the author of several books. Until 2010, he was also an adjunct associate professor in the Faculty of Information Technology at Monash University.

Berkeley Yacc (byacc) is a Unix parser generator designed to be compatible with Yacc. It was originally written by Robert Corbett and released in 1989. Due to its liberal license and because it was faster than the AT&T Yacc, it quickly became the most popular version of Yacc. It has the advantages of being written in ANSI C89 and being public domain software.

LAMP is an acronym denoting one of the most common software stacks for the web's most popular applications. Its generic software stack model has largely interchangeable components.

Raku rules are the regular expression, string matching and general-purpose parsing facility of the Raku programming language, and are a core part of the language. Since Perl's pattern-matching constructs have exceeded the capabilities of formal regular expressions for some time, Raku documentation refers to them exclusively as regexes, distancing the term from the formal definition.

The Parser Grammar Engine is a compiler and runtime for Raku rules for the Parrot virtual machine. PGE uses these rules to convert a parsing expression grammar into Parrot bytecode. It is therefore compiling rules into a program, unlike most virtual machines and runtimes, which store regular expressions in a secondary internal format that is then interpreted at runtime by a regular expression engine. The rules format used by PGE can express any regular expression and most formal grammars, and as such it forms the first link in the compiler chain for all of Parrot's front-end languages.

Test::More is a unit testing module for Perl. Created and maintained by Michael G Schwern with help from Barrie Slaymaker, Tony Bowden, chromatic, Fergal Daly and perl-qa.

Sass is a preprocessor scripting language that is interpreted or compiled into Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). SassScript is the scripting language itself.

Rakudo is a Raku compiler targeting MoarVM, and the Java Virtual Machine, that implements the Raku specification. It is currently the only major Raku compiler in active development.

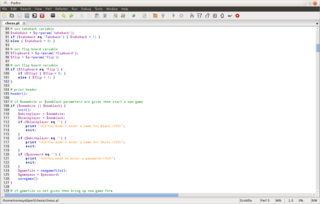

Padre is a multi-language software development platform comprising an IDE and a plug-in system to extend it. It is written primarily in Perl and is used to develop applications in this language.

Haskell is a general-purpose, statically-typed, purely functional programming language with type inference and lazy evaluation. Designed for teaching, research, and industrial applications, Haskell has pioneered a number of programming language features such as type classes, which enable type-safe operator overloading, and monadic input/output (IO). It is named after logician Haskell Curry. Haskell's main implementation is the Glasgow Haskell Compiler (GHC).

Rust is a multi-paradigm, general-purpose programming language that emphasizes performance, type safety, and concurrency. It enforces memory safety—meaning that all references point to valid memory—without a garbage collector. To simultaneously enforce memory safety and prevent data races, its "borrow checker" tracks the object lifetime of all references in a program during compilation.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Perl programming language:

MoarVM is a virtual machine built for the 6model object system. It is being built to serve as yet another VM backend for Raku. MoarVM was created to allow for greater efficiency than Parrot by having a closer internal representation to the model system used by Raku. Notably it was the virtual machine for the first stable version of Rakudo released in December 2015.

Nim is a general-purpose, multi-paradigm, statically typed, compiled high-level systems programming language, designed and developed by a team around Andreas Rumpf. Nim is designed to be "efficient, expressive, and elegant", supporting metaprogramming, functional, message passing, procedural, and object-oriented programming styles by providing several features such as compile time code generation, algebraic data types, a foreign function interface (FFI) with C, C++, Objective-C, and JavaScript, and supporting compiling to those same languages as intermediate representations.