Reduced affect display, sometimes referred to as emotional blunting or emotional numbing, is a condition of reduced emotional reactivity in an individual. It manifests as a failure to express feelings either verbally or nonverbally, especially when talking about issues that would normally be expected to engage emotions. In this condition, expressive gestures are rare and there is little animation in facial expression or vocal inflection. [1] Additionally, reduced affect can be symptomatic of autism, schizophrenia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, depersonalization disorder, [2] [3] [4] schizoid personality disorder or brain damage. [5] It may also be a side effect of certain medications (e.g., antipsychotics [6] and antidepressants [7] ).

However, reduced affect should be distinguished from apathy and anhedonia, which explicitly refer to a lack of emotional sensation.

A restricted or constricted affect is a reduction in an individual's expressive range and the intensity of emotional responses. [8]

Blunted affect is a lack of affect more severe than restricted or constricted affect, but less severe than flat or flattened affect. "The difference between flat and blunted affect is in degree. A person with flat affect has no or nearly no emotional expression. They may not react at all to circumstances that usually evoke strong emotions in others. A person with blunted affect, on the other hand, has a significantly reduced intensity in emotional expression". [9]

Shallow affect has an equivalent meaning to blunted affect. In the Psychopathy Checklist, Factor 1 identifies shallow affect as a common attribute of psychopathy. [10]

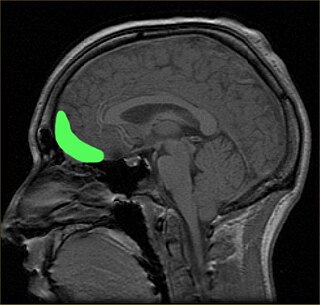

Individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect show different regional brain activity in fMRI scans when presented with emotional stimuli compared to individuals with schizophrenia without blunted affect. For instance, individuals with schizophrenia without blunted affect show activation in the following brain areas when shown emotionally negative pictures: midbrain, pons, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, ventrolateral orbitofrontal cortex, anterior temporal pole, amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex and extrastriate visual cortex. Whereas, individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect show activation in the following brain regions when shown emotionally negative pictures: midbrain, pons, anterior temporal pole and extrastriate visual cortex. [11]

Individuals with schizophrenia with flat affect show decreased activation in the limbic system when viewing emotional stimuli. In individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect neural processes begin in the occipitotemporal region of the brain and go through the ventral visual pathway and the limbic structures until they reach the inferior frontal areas. [11] Damage to the amygdala of adult rhesus macaques early in life can permanently alter affective processing. Lesioning the amygdala causes blunted affect responses to both positive and negative stimuli. This effect is irreversible in the rhesus macaques; neonatal damage produces the same effect as damage that occurs later in life. The macaques' brain cannot compensate for early amygdala damage, even though significant neuronal growth may occur. [12] There is some evidence that blunted affect symptoms in schizophrenia patients are not a result of just amygdala responsiveness, but a result of the amygdala not being integrated with other areas of the brain associated with emotional processing, particularly in amygdala-prefrontal cortex coupling. [13] Damage in the limbic region prevents the amygdala from correctly interpreting emotional stimuli in individuals with schizophrenia by compromising the link between the amygdala and other brain regions associated with emotion. [11]

Parts of the brainstem are responsible for passive emotional coping strategies characterized by disengagement or withdrawal from the external environment (quiescence, immobility, hyporeactivity), similar to what is seen in blunted affect. Individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect show activation of the brainstem during fMRI scans, particularly the right medulla and the left pons, when shown "sad" film excerpts. [14] The bilateral midbrain is also activated in individuals with schizophrenia diagnosed with blunted affect. Activation of the midbrain is thought to be related to autonomic responses associated with the perceptual processing of emotional stimuli. This region usually becomes activated in diverse emotional states. When the connectivity between the midbrain and the medial prefrontal cortex is compromised in individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect an absence of emotional reaction to external stimuli results. [11]

Individuals with schizophrenia, as well as patients being successfully reconditioned with quetiapine for blunted affect, show activation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Failure to activate the PFC is possibly involved in impaired emotional processing in individuals with schizophrenia with blunted affect. The medial PFC is activated in average individuals in response to external emotional stimuli. This structure possibly receives information from the limbic structures to regulate emotional experiences and behavior. Individuals being reconditioned with quetiapine, who show reduced symptoms, show activation in other areas of the PFC as well, including the right medial prefrontal gyrus and the left orbitofrontal gyrus. [14]

A positive correlation has been found between activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and the reported magnitude of sad feelings evoked by viewing sad film excerpts. The rostral subdivision of this region is possibly involved in detecting emotional signals. This region is different in individuals with schizophrenia, with blunted affect. [11]

Flat and blunted affect is a defining characteristic in the presentation of schizophrenia. To reiterate, these individuals have a decrease in observed vocal and facial expressions as well as the use of gestures. [15] One study of flat affect in schizophrenia found that "flat affect was more common in men and was associated with worse current quality of life" as well as having "an adverse effect on course of illness". [16]

The study also reported a "dissociation between reported experience of emotion and its display" [16] – supporting the suggestion made elsewhere that "blunted affect, including flattened facial expressiveness and lack of vocal inflection ... often disguises an individual's true feelings." [17] Thus, feelings may merely be unexpressed, rather than lacking. On the other hand, "a lack of emotions which is due not to mere repression but to a real loss of contact with the objective world gives the observer a specific impression of 'queerness' ... the remainders of emotions or the substitutes for emotions usually refer to rage and aggressiveness". [18] In the most extreme cases, there is a complete "dissociation from affective states". [19] To further support this idea, a study examining emotion dysregulation found that individuals with schizophrenia could not exaggerate their emotional expression as healthy controls could. Participants were asked to express whatever emotions they had during a clip of a film, and the participants with schizophrenia showed deficits in the behavioral expression of their emotions. [20]

There is still some debate regarding the source of flat affect in schizophrenia. However, some literature indicates abnormalities in the dorsal executive and ventral affective systems; it is argued that dorsal hypoactivation and ventral hyperactivation may be the source of flat affect. [21] Further, the authors found deficits in the mirror neuron system may also contribute to flat affect in that the deficits may cause disruptions in the control of facial expression.

Another study found that when speaking, individuals with schizophrenia with flat affect demonstrate less inflection than normal controls and appear to be less fluent. Normal subjects appear to express themselves using more complex syntax, whereas flat affect subjects speak with fewer words, and fewer words per sentence. Flat affect individuals' use of context-appropriate words in both sad and happy narratives are similar to that of controls. It is very likely that flat affect is a result of deficits in motor expression as opposed to emotional processing. The moods of display are compromised, but subjective, autonomic, and contextual aspects of emotion are left intact. [22]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was previously known to cause negative feelings, such as depressed mood, re-experiencing and hyperarousal. However, recently, psychologists have started to focus their attention on the blunted affects and also the decrease in feeling and expressing positive emotions in PTSD patients. [23] Blunted affect, or emotional numbness, is considered one of the consequences of PTSD because it causes a diminished interest in activities that produce pleasure (anhedonia) and produces feelings of detachment from others, restricted emotional expression and a reduced tendency to express emotions behaviorally. Blunted affect is often seen in veterans as a consequence of the psychological stressful experiences that caused PTSD. [23] Blunted affect is a response to PTSD, it is considered one of the central symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorders and it is often seen in veterans who served in combat zones. [24] In PTSD, blunted affect can be considered a psychological response to PTSD as a way to combat overwhelming anxiety that the patients feel. [25] In blunted affect, there are abnormalities in circuits that also include the prefrontal cortex. [26] [27]

In making assessments of mood and affect the clinician is cautioned that "it is important to keep in mind that demonstrative expression can be influenced by cultural differences, medication, or situational factors"; [5] while the layperson is warned to beware of applying the criterion lightly to "friends, otherwise [he or she] is likely to make false judgments, in view of the prevalence of schizoid and cyclothymic personalities in our 'normal' population, and our [US] tendency to psychological hypochondriasis". [28]

R. D. Laing in particular stressed that "such 'clinical' categories as schizoid, autistic, 'impoverished' affect ... all presuppose that there are reliable, valid impersonal criteria for making attributions about the other person's relation to [his or her] actions. There are no such reliable or valid criteria". [29]

Blunted affect is very similar to anhedonia, which is the decrease or cessation of all feelings of pleasure (which thus affects enjoyment, happiness, fun, interest, and satisfaction). In the case of anhedonia, emotions relating to pleasure will not be expressed as much or at all because they are literally not experienced or are decreased. Both blunted affect and anhedonia are considered negative symptoms of schizophrenia, meaning that they are indicative of a lack of something. There are some other negative symptoms of schizophrenia which include avolition, alogia and catatonic behaviour.

Closely related is alexithymia – a condition describing people who "lack words for their feelings. They seem to lack feelings altogether, although this may actually be because of their inability to express emotion rather than from an absence of emotion altogether". [30] Alexithymic patients however can provide clues via assessment presentation which may be indicative of emotional arousal. [31]

"If the amygdala is severed from the rest of the brain, the result is a striking inability to gauge the emotional significance of events; this condition is sometimes called 'affective blindness'". [32] In some cases, blunted affect can fade, but there is no conclusive evidence of why this can occur.

A phobia is an anxiety disorder, defined by an irrational, unrealistic, persistent and excessive fear of an object or situation. Phobias typically result in a rapid onset of fear and are usually present for more than six months. Those affected go to great lengths to avoid the situation or object, to a degree greater than the actual danger posed. If the object or situation cannot be avoided, they experience significant distress. Other symptoms can include fainting, which may occur in blood or injury phobia, and panic attacks, often found in agoraphobia and emetophobia. Around 75% of those with phobias have multiple phobias.

The amygdala is a paired nuclear complex present in the cerebral hemispheres of vertebrates. It is considered part of the limbic system. In primates, it is located medially within the temporal lobes. It consists of many nuclei, each made up of further subnuclei. The subdivision most commonly made is into the basolateral, central, cortical, and medial nuclei together with the intercalated cell clusters. The amygdala has a primary role in the processing of memory, decision-making, and emotional responses. The amygdala was first identified and named by Karl Friedrich Burdach in 1822.

Anhedonia is a diverse array of deficits in hedonic function, including reduced motivation or ability to experience pleasure. While earlier definitions emphasized the inability to experience pleasure, anhedonia is currently used by researchers to refer to reduced motivation, reduced anticipatory pleasure (wanting), reduced consummatory pleasure (liking), and deficits in reinforcement learning. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), anhedonia is a component of depressive disorders, substance-related disorders, psychotic disorders, and personality disorders, where it is defined by either a reduced ability to experience pleasure, or a diminished interest in engaging in previously pleasurable activities. While the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) does not explicitly mention anhedonia, the depressive symptom analogous to anhedonia as described in the DSM-5 is a loss of interest or pleasure.

A mood swing is an extreme or sudden change of mood. Such changes can play a positive part in promoting problem solving and in producing flexible forward planning, or be disruptive. When mood swings are severe, they may be categorized as part of a mental illness, such as bipolar disorder, where erratic and disruptive mood swings are a defining feature.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

In psychology, emotional detachment, also known as emotional blunting, is a condition or state in which a person lacks emotional connectivity to others, whether due to an unwanted circumstance or as a positive means to cope with anxiety. Such a coping strategy, also known as emotion-focused coping, is used when avoiding certain situations that might trigger anxiety. It refers to the evasion of emotional connections. Emotional detachment may be a temporary reaction to a stressful situation, or a chronic condition such as depersonalization-derealization disorder. It may also be caused by certain antidepressants. Emotional blunting, also known as reduced affect display, is one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a prefrontal cortex region in the frontal lobes of the brain which is involved in the cognitive process of decision-making. In non-human primates it consists of the association cortex areas Brodmann area 11, 12 and 13; in humans it consists of Brodmann area 10, 11 and 47.

The reward system is a group of neural structures responsible for incentive salience, associative learning, and positively-valenced emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure as a core component. Reward is the attractive and motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior, also known as approach behavior, and consummatory behavior. A rewarding stimulus has been described as "any stimulus, object, event, activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and consume it is by definition a reward". In operant conditioning, rewarding stimuli function as positive reinforcers; however, the converse statement also holds true: positive reinforcers are rewarding.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex in the mammalian brain. The ventral medial prefrontal is located in the frontal lobe at the bottom of the cerebral hemispheres and is implicated in the processing of risk and fear, as it is critical in the regulation of amygdala activity in humans. It also plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, and in the process of decision-making and self-control. It is also involved in the cognitive evaluation of morality.

Memory and trauma is the deleterious effects that physical or psychological trauma has on memory.

Paradoxical laughter is an exaggerated expression of humour which is unwarranted by external events. It may be uncontrollable laughter which may be recognised as inappropriate by the person involved. It is associated with mental illness, such as mania, hypomania or schizophrenia, schizotypal personality disorder and can have other causes. Paradoxical laughter is indicative of an unstable mood, often caused by the pseudobulbar affect, which can quickly change to anger and back again, on minor external cues.

Emotional responsivity is the ability to acknowledge an affective stimuli by exhibiting emotion. It is a sharp change of emotion according to a person's emotional state. Increased emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating more response to a stimulus. Reduced emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating less response to a stimulus. Any response exhibited after exposure to the stimulus, whether it is appropriate or not, would be considered as an emotional response. Although emotional responsivity applies to nonclinical populations, it is more typically associated with individuals with schizophrenia and autism.

Scientific studies have found that different brain areas show altered activity in humans with major depressive disorder (MDD), and this has encouraged advocates of various theories that seek to identify a biochemical origin of the disease, as opposed to theories that emphasize psychological or situational causes. Factors spanning these causative groups include nutritional deficiencies in magnesium, vitamin D, and tryptophan with situational origin but biological impact. Several theories concerning the biologically based cause of depression have been suggested over the years, including theories revolving around monoamine neurotransmitters, neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, inflammation and the circadian rhythm. Physical illnesses, including hypothyroidism and mitochondrial disease, can also trigger depressive symptoms.

Emotional lateralization is the asymmetrical representation of emotional control and processing in the brain. There is evidence for the lateralization of other brain functions as well.

Parental experience, as well as changing hormone levels during pregnancy and postpartum, cause changes in the parental brain. Displaying maternal sensitivity towards infant cues, processing those cues and being motivated to engage socially with her infant and attend to the infant's needs in any context could be described as mothering behavior and is regulated by many systems in the maternal brain. Research has shown that hormones such as oxytocin, prolactin, estradiol and progesterone are essential for the onset and the maintenance of maternal behavior in rats, and other mammals as well. Mothering behavior has also been classified within the basic drives.

Emotion perception refers to the capacities and abilities of recognizing and identifying emotions in others, in addition to biological and physiological processes involved. Emotions are typically viewed as having three components: subjective experience, physical changes, and cognitive appraisal; emotion perception is the ability to make accurate decisions about another's subjective experience by interpreting their physical changes through sensory systems responsible for converting these observed changes into mental representations. The ability to perceive emotion is believed to be both innate and subject to environmental influence and is also a critical component in social interactions. How emotion is experienced and interpreted depends on how it is perceived. Likewise, how emotion is perceived is dependent on past experiences and interpretations. Emotion can be accurately perceived in humans. Emotions can be perceived visually, audibly, through smell and also through bodily sensations and this process is believed to be different from the perception of non-emotional material.

Mindfulness has been defined in modern psychological terms as "paying attention to relevant aspects of experience in a nonjudgmental manner", and maintaining attention on present moment experience with an attitude of openness and acceptance. Meditation is a platform used to achieve mindfulness. Both practices, mindfulness and meditation, have been "directly inspired from the Buddhist tradition" and have been widely promoted by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have a positive impact on several psychiatric problems such as depression and therefore has formed the basis of mindfulness programs such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based pain management. The applications of mindfulness meditation are well established, however the mechanisms that underlie this practice are yet to be fully understood. Many tests and studies on soldiers with PTSD have shown tremendous positive results in decreasing stress levels and being able to cope with problems of the past, paving the way for more tests and studies to normalize and accept mindful based meditation and research, not only for soldiers with PTSD, but numerous mental inabilities or disabilities.

Emotions play a key role in overall mental health, and sleep plays a crucial role in maintaining the optimal homeostasis of emotional functioning. Deficient sleep, both in the form of sleep deprivation and restriction, adversely impacts emotion generation, emotion regulation, and emotional expression.

Bipolar disorder is an affective disorder characterized by periods of elevated and depressed mood. The cause and mechanism of bipolar disorder is not yet known, and the study of its biological origins is ongoing. Although no single gene causes the disorder, a number of genes are linked to increase risk of the disorder, and various gene environment interactions may play a role in predisposing individuals to developing bipolar disorder. Neuroimaging and postmortem studies have found abnormalities in a variety of brain regions, and most commonly implicated regions include the ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Dysfunction in emotional circuits located in these regions have been hypothesized as a mechanism for bipolar disorder. A number of lines of evidence suggests abnormalities in neurotransmission, intracellular signalling, and cellular functioning as possibly playing a role in bipolar disorder.

Affect labeling is an implicit emotional regulation strategy that can be simply described as "putting feelings into words". Specifically, it refers to the idea that explicitly labeling one's, typically negative, emotional state results in a reduction of the conscious experience, physiological response, and/or behavior resulting from that emotional state. For example, writing about a negative experience in one's journal may improve one's mood. Some other examples of affect labeling include discussing one's feelings with a therapist, complaining to friends about a negative experience, posting one's feelings on social media or acknowledging the scary aspects of a situation.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)