Related Research Articles

Jules Cotard was a French physician who practiced neurology and psychiatry. He is best known for first describing the Cotard delusion, a patient's delusional belief that they are dead, do not exist or do not have bodily organs.

Capgras delusion or Capgras syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a person holds a delusion that a friend, spouse, parent, another close family member, or pet has been replaced by an identical impostor. It is named after Joseph Capgras (1873–1950), the French psychiatrist who first described the disorder.

The Fregoli delusion is a rare disorder in which a person holds a delusional belief that different people are in fact a single person who changes appearance or is in disguise. The syndrome may be related to a brain lesion and is often of a paranoid nature, with the delusional person believing themselves persecuted by the person they believe is in disguise.

Brain injury (BI) is the destruction or degeneration of brain cells. Brain injuries occur due to a wide range of internal and external factors. In general, brain damage refers to significant, undiscriminating trauma-induced damage.

Delusional misidentification syndrome is an umbrella term, introduced by Christodoulou for a group of four delusional disorders that occur in the context of mental and neurological illness. They are grouped together as they often occur simultaneously or interchange, and they display the common concept of the double (sosie). They all involve a belief that the identity of a person, object, or place has somehow changed or has been altered. Christodoulu further categorized these disorders into those including hypo -identification of a well-known person, and hyper -identification of an unknown person. As these delusions typically only concern one particular topic, they also fall under the category called monothematic delusions.

Cognitive neuropsychology is a branch of cognitive psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes. Cognitive psychology is the science that looks at how mental processes are responsible for the cognitive abilities to store and produce new memories, produce language, recognize people and objects, as well as our ability to reason and problem solve. Cognitive neuropsychology places a particular emphasis on studying the cognitive effects of brain injury or neurological illness with a view to inferring models of normal cognitive functioning. Evidence is based on case studies of individual brain damaged patients who show deficits in brain areas and from patients who exhibit double dissociations. Double dissociations involve two patients and two tasks. One patient is impaired at one task but normal on the other, while the other patient is normal on the first task and impaired on the other. For example, patient A would be poor at reading printed words while still being normal at understanding spoken words, while the patient B would be normal at understanding written words and be poor at understanding spoken words. Scientists can interpret this information to explain how there is a single cognitive module for word comprehension. From studies like these, researchers infer that different areas of the brain are highly specialised. Cognitive neuropsychology can be distinguished from cognitive neuroscience, which is also interested in brain-damaged patients, but is particularly focused on uncovering the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive processes.

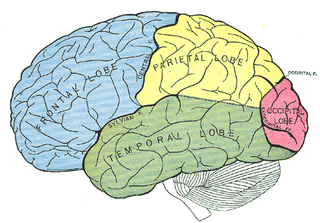

Anosognosia is a condition in which a person with a disability is cognitively unaware of having it due to an underlying physical condition. Anosognosia results from physiological damage to brain structures, typically to the parietal lobe or a diffuse lesion on the fronto-temporal-parietal area in the right hemisphere, and is thus a neuropsychiatric disorder. A deficit of self-awareness, the term was first coined by the neurologist Joseph Babinski in 1914, in order to describe the unawareness of hemiplegia.

Bálint's syndrome is an uncommon and incompletely understood triad of severe neuropsychological impairments: inability to perceive the visual field as a whole (simultanagnosia), difficulty in fixating the eyes, and inability to move the hand to a specific object by using vision. It was named in 1909 for the Austro-Hungarian neurologist and psychiatrist Rezső Bálint who first identified it.

Intermetamorphosis is a delusional misidentification syndrome, related to agnosia. The main symptoms consist of patients believing that they can see others change into someone else in both external appearance and internal personality. The disorder is usually comorbid with neurological disorders or mental disorders. The disorder was first described in 1932 by Paul Courbon (1879–1958), a French psychiatrist. Intermetamorphosis is rare, although issues with diagnostics and comorbidity may lead to under-reporting.

The syndrome of subjective doubles is a rare delusional misidentification syndrome in which a person experiences the delusion that they have a double or Doppelgänger with the same appearance, but usually with different character traits, that is leading a life of its own. The syndrome is also called the syndrome of doubles of the self, delusion of subjective doubles, or simply subjective doubles. Sometimes, the patient is under the impression that there is more than one double. A double may be projected onto any person, from a stranger to a family member.

Acalculia is an acquired impairment in which people have difficulty performing simple mathematical tasks, such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and even simply stating which of two numbers is larger. Acalculia is distinguished from dyscalculia in that acalculia is acquired late in life due to neurological injury such as stroke, while dyscalculia is a specific developmental disorder first observed during the acquisition of mathematical knowledge. The name comes from the Greek a- meaning "not" and Latin calculare, which means "to count".

Mirrored-self misidentification is the delusional belief that one's reflection in the mirror is another person – typically a younger or second version of one's self, a stranger, or a relative. This delusion occurs most frequently in patients with dementia and an affected patient maintains the ability to recognize others' reflections in the mirror. It is caused by right hemisphere cranial dysfunction that results from traumatic brain injury, stroke, or general neurological illness. It is an example of a monothematic delusion, a condition in which all abnormal beliefs have one common theme, as opposed to a polythematic delusion, in which a variety of unrelated delusional beliefs exist. This delusion is also classified as one of the delusional misidentification syndromes (DMS). A patient with a DMS condition consistently misidentifies places, objects, persons, or events. DMS patients are not aware of their psychological condition, are resistant to correction and their conditions are associated with brain disease – particularly right hemisphere brain damage and dysfunction.

A monothematic delusion is a delusional state that concerns only one particular topic. This is contrasted by what is sometimes called multi-thematic or polythematic delusions where the person has a range of delusions. These disorders can occur within the context of schizophrenia or dementia or they can occur without any other signs of mental illness. When these disorders are found outside the context of mental illness, they are often caused by organic dysfunction as a result of traumatic brain injury, stroke, or neurological illness.

Memory disorders are the result of damage to neuroanatomical structures that hinders the storage, retention and recollection of memories. Memory disorders can be progressive, including Alzheimer's disease, or they can be immediate including disorders resulting from head injury.

Frontal lobe disorder, also frontal lobe syndrome, is an impairment of the frontal lobe of the brain due to disease or frontal lobe injury. The frontal lobe plays a key role in executive functions such as motivation, planning, social behaviour, and speech production. Frontal lobe syndrome can be caused by a range of conditions including head trauma, tumours, neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, neurosurgery and cerebrovascular disease. Frontal lobe impairment can be detected by recognition of typical signs and symptoms, use of simple screening tests, and specialist neurological testing.

Post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) is a state of confusion that occurs immediately following a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in which the injured person is disoriented and unable to remember events that occur after the injury. The person may be unable to state their name, where they are, and what time it is. When continuous memory returns, PTA is considered to have resolved. While PTA lasts, new events cannot be stored in the memory. About a third of patients with mild head injury are reported to have "islands of memory", in which the patient can recall only some events. During PTA, the patient's consciousness is "clouded". Because PTA involves confusion in addition to the memory loss typical of amnesia, the term "post-traumatic confusional state" has been proposed as an alternative.

Topographical disorientation is the inability to orient oneself in one's surroundings, sometimes as a result of focal brain damage. This disability may result from the inability to make use of selective spatial information or to orient by means of specific cognitive strategies such as the ability to form a mental representation of the environment, also known as a cognitive map. It may be part of a syndrome known as visuospatial dysgnosia.

In psychology, confabulation is a memory error consisting of the production of fabricated, distorted, or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world. It is generally associated with certain types of brain damage or a specific subset of dementias. While still an area of ongoing research, the basal forebrain is implicated in the phenomenon of confabulation. People who confabulate present with incorrect memories ranging from subtle inaccuracies to surreal fabrications, and may include confusion or distortion in the temporal framing of memories. In general, they are very confident about their recollections, even when challenged with contradictory evidence.

Cotard's syndrome, also known as Cotard's delusion or walking corpse syndrome, is a rare mental disorder in which the affected person holds the delusional belief that they are dead, do not exist, are putrefying, or have lost their blood or internal organs. Statistical analysis of a hundred-patient cohort indicated that denial of self-existence is present in 45% of the cases of Cotard's syndrome; the other 55% of the patients presented with delusions of immortality.

Donald Thomas Stuss was a Canadian neuropsychologist who studied the frontal lobes of the human brain. He also directed the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest from 1989 until 2009 and the Ontario Brain Institute from 2011 until 2016.

References

- ↑ ABPN, Arthur MacNeill Horton, Jr , EdD, ABPP; ABN, Chad A. Noggle, PhD; ABPdN, Raymond S. Dean, PhD, ABPP, ABN (2011-10-25). The Encyclopedia of Neuropsychological Disorders. Springer Publishing Company. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8261-9855-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Granacher, Jr , Robert P. (2003-06-27). Traumatic Brain Injury: Methods for Clinical and Forensic Neuropsychiatric Assessment. CRC Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-203-50174-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Forstl H.; Almeida O.P.; Owen A.M.; Burns A.; Howard R. (1991). "Psychiatric, neurological and medical aspects of misidentification syndromes: a review of 260 cases". Psychological Medicine. 21 (4): 905–10. doi:10.1017/S0033291700029895. PMID 1780403. S2CID 24026245.

- ↑ Fisher C.M. (1982). "Disorientation for place". Archives of Neurology. 39 (1): 33–6. doi:10.1001/archneur.1982.00510130035008. PMID 7055444.

- ↑ Weinstein, E.A. & Kahn, R.L. (1955) Denial of Illness: Symbolic and Physiological Aspects. Springfield, IL: Thomas.

- 1 2 Paterson A.; Zangwill O. (1944). "Recovery of spatial orientation in the post-traumatic confusional state". Brain. 67: 54–68. doi:10.1093/brain/67.1.54.

- 1 2 Pick A (1903). "On reduplicative paramnesia". Brain. 26 (2): 242–267. doi:10.1093/brain/26.2.242.

- 1 2 Benson DF, Gardner H, Meadows JC (February 1976). "Reduplicative paramnesia". Neurology. 26 (2): 147–51. doi:10.1212/wnl.26.2.147. PMID 943070. S2CID 41547561.

- ↑ Sellal F.; Fontaine S.F.; van der Linden M.; Rainville C.; Labrecque R. (1996). "To be or not to be at home? A neuropsychological approach to delusion for place. Journal". Of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 18 (2): 234–48. doi:10.1080/01688639608408278. hdl: 2268/179082 . PMID 8780958.

- ↑ Budson A.E.; Roth H.L.; Rentz D.M.; Ronthal M. (2000). "Disruption of the ventral visual stream in a case of reduplicative paramnesia". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 911 (1): 447–52. Bibcode:2000NYASA.911..447B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06742.x. PMID 10911890. S2CID 13943779.

- ↑ Charles Bonnet's description of Cotard's delusion and reduplicative paramnesia in an elderly patient (1788) Förstl H, Beats B (March 1992). "Charles Bonnet's description of Cotard's delusion and reduplicative paramnesia in an elderly patient (1788)" (PDF). British Journal of Psychiatry . 160 (3): 416–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.160.3.416. PMID 1562875. S2CID 8421104.

- ↑ Head, H. (1926) Aphasia and Kindred Disorders. London: Cambridge University Press.