The United Provinces of the Netherlands, officially the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, and commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands and the first independent Dutch state. The republic was established after seven Dutch provinces in the Spanish Netherlands revolted against Spanish rule, forming a mutual alliance against Spain in 1579 and declaring their independence in 1581. It comprised Groningen, Frisia, Overijssel, Guelders, Utrecht, Holland and Zeeland.

In the Low Countries, a stadtholder was a steward, first appointed as a medieval official and ultimately functioning as a national leader. The stadtholder was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and Habsburg period.

Johan de Witt, lord of Zuid- en Noord-Linschoten, Snelrewaard, Hekendorp en IJsselvere, was a Dutch statesman and a major political figure in the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century, the First Stadtholderless Period, when its flourishing sea trade in a period of global colonisation made the republic a leading European trading and seafaring power – now commonly referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. De Witt was elected Grand pensionary of Holland, and together with his uncle Cornelis de Graeff, he controlled the Dutch political system from around 1650 until the Rampjaar of 1672. This progressive cooperation between the two statesmen, and the consequent support of Amsterdam under the rule of De Graeff, was an important political axis that organized the political system within the republic.

The Patriottentijd was a period of political instability in the Dutch Republic between approximately 1780 and 1787. Its name derives from the Patriots faction who opposed the rule of the stadtholder, William V, Prince of Orange, and his supporters who were known as Orangists.

The Batavian Revolution was a time of political, social and cultural turmoil at the end of the 18th century that marked the end of the Dutch Republic and saw the proclamation of the Batavian Republic.

The First Stadtholderless Period or Era is the period in the history of the Dutch Republic in which the office of Stadtholder was vacant in five of the seven Dutch provinces. It coincided with the zenith of the Golden Age of the Republic.

The Perpetual Edict was a resolution of the States of Holland passed on 5 August 1667 which abolished the office of Stadtholder in the province of Holland. At approximately the same time, a majority of provinces in the States General of the Netherlands agreed to declare the office of stadtholder incompatible with the office of Captain general of the Dutch Republic.

The Second Stadtholderless Period or Era is the designation in Dutch historiography of the period between the death of stadtholder William III on March 19, 1702, and the appointment of William IV as stadtholder and captain general in all provinces of the Dutch Republic on 2 May 1747. During this period the office of stadtholder was left vacant in the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht, though in other provinces that office was filled by members of the House of Nassau-Dietz during various periods. During the period the Republic lost its status as a great power and its primacy in world trade. Though its economy declined considerably, causing deindustralization and deurbanization in the maritime provinces, a rentier-class kept accumulating a large capital fund that formed the basis for the leading position the Republic achieved in the international capital market. A military crisis at the end of the period caused the fall of the States-Party regime and the restoration of the Stadtholderate in all provinces. However, though the new stadtholder acquired near-dictatorial powers, this did not improve the situation.

In the history of the Dutch Republic, Orangism or prinsgezindheid was a political force opposing the Staatsgezinde (pro-Republic) party. Orangists supported the Princes of Orange as Stadtholders and military commanders of the Republic, as a check on the power of the regenten. The Orangist party drew its adherents largely from traditionalists – mostly farmers, soldiers, noblemen and orthodox Protestant preachers, though its support fluctuated heavily over the course of the Republic's history and there were never clear-cut socioeconomic divisions.

The Dutch Republic existed from 1579 to 1795 and was a confederation of seven provinces, which had their own governments and were very independent, and a number of so-called Generality Lands. These latter were governed directly by the States-General, the federal government. The States-General were seated in The Hague and consisted of representatives of each of the seven provinces.

Daniël Raap was a porcelain merchant who played a leading role during the Orangist revolution in the Netherlands of 1747–1751.

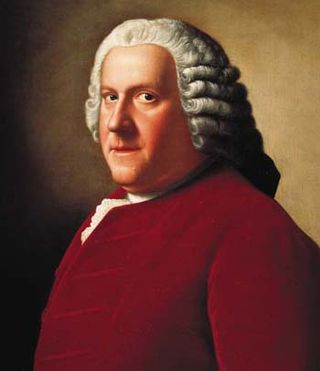

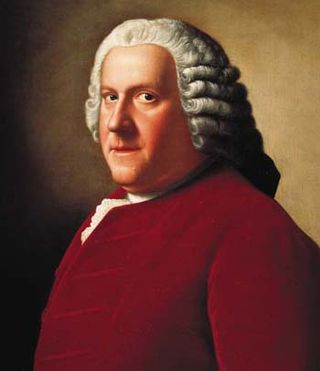

Willem, Count Bentinck, Lord of Rhoon and Pendrecht was a Dutch nobleman and politician, and the eldest son from the second marriage of William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland. He was created Count Bentinck of the Holy Roman Empire in 1732. Bentinck played a leading role in the Orangist revolution of 1747 in the Netherlands.

The Dutch States Party was a political faction of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. This republican faction is usually (negatively) defined as the opponents of the Orangist, or Prinsgezinde faction, who supported the monarchical aspirations of the stadtholders, who were usually members of the House of Orange-Nassau. The two factions existed during the entire history of the Republic since the Twelve Years' Truce, be it that the role of "usual opposition party" of the States Party was taken over by the Patriots after the Orangist revolution of 1747. The States Party was in the ascendancy during the First Stadtholderless Period and the Second Stadtholderless Period.

The Leiden Draft is the translation used in Anglophone historiography of the Dutch-language concept Leids Ontwerp, a draft-manifesto discussed by the Holland congress of representatives of exercitiegenootschappen on 8 October 1785 in Leiden in the context of the so-called Patriot revolution of 1785 in the Dutch Republic. This draft resulted in publication of the manifesto entitled Ontwerp om de Republiek door eene heilzaame Vereeniging van Belangen van Regent en Burger van Binnen Gelukkig en van Buiten Gedugt te maaken, Leiden, aangenomen bij besluit van de Provinciale Vergadering van de Gewapende Corpsen in Holland, op 4 oktober 1785 te Leiden. It contained an exposition of the Patriot ideology and arrived at the formulation of twenty proposals of political reform in a democratic vein.

The Attack on Amsterdam in July 1650 was part of a planned coup d'état by stadtholder William II, Prince of Orange to break the power of the regenten in the Dutch Republic, especially the County of Holland. The coup failed, because the army of the Frisian stadtholder William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz got lost on the way to Amsterdam in the rainy night of 29 to 30 July. It was discovered, and once the city had been warned, it had enough time to prepare for an attack. The attempted coup made the House of Orange extremely unpopular for a lengthy period of time, and was one of the main reasons for the origins of the First Stadtholderless Period (1650–1672).

Joachim Rendorp, Vrijheer of Marquette was a Dutch politician of the Patriottentijd in the Dutch Republic.

Willem Gerrit Dedel SalomonszoonAmbachtsheer of Sloten and Sloterdijk was a Dutch politician during the Patriottentijd in the Dutch Republic.

The States of Friesland were the sovereign body that governed the province of Friesland under the Dutch Republic. They were formed in 1580 after the former Lordship of Frisia acceded to the Union of Utrecht and became one of the Seven United Netherlands. The Frisian stadtholder was their "First Servant". The board of Gedeputeerde Staten was the executive of the province when the States were not in session. The States of Friesland were abolished after the Batavian Revolution of 1795 when the Batavian Republic was founded. They were resurrected in name in the form of the Provincial States of Friesland under the Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The aftermath of the Eighty Years' War had far-reaching military, political, socio-economic, religious, and cultural effects on the Low Countries, the Spanish Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, as well as other regions of Europe and European colonies overseas. By the Peace of Münster, the Habsburg Netherlands were split in two, with the northern Protestant-dominated Netherlands becoming the Dutch Republic, independent of the Spanish and Holy Roman Empires, while the southern Catholic-dominated Spanish Netherlands remained under Spanish Habsburg sovereignty. Whereas the Spanish Empire and the Southern Netherlands along with it were financially and demographically ruined, declining politically and economically, the Dutch Republic became a global commercial power and achieved a high level of prosperity for its upper and middle classes known as the Dutch Golden Age, despite continued great socio-economic, geographic and religious inequalities and problems, as well as internal and external political, military and religious conflicts.

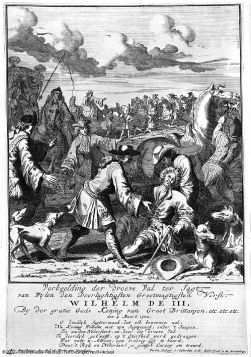

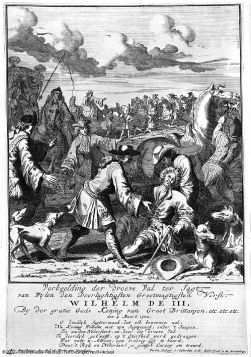

The Orangist revolution of 1747 brought William IV, Prince of Orange to the Stadtholder office, finishing the Second Stadtholderless Period.