The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is the statute establishing federal U.S. drug policy under which the manufacture, importation, possession, use, and distribution of certain substances is regulated. It was passed by the 91st United States Congress as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 and signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The Act also served as the national implementing legislation for the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

The United States Food and Drug Administration is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food safety, tobacco products, caffeine products, dietary supplements, prescription and over-the-counter pharmaceutical drugs (medications), vaccines, biopharmaceuticals, blood transfusions, medical devices, electromagnetic radiation emitting devices (ERED), cosmetics, animal foods & feed and veterinary products.

A medication is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and relies on the science of pharmacology for continual advancement and on pharmacy for appropriate management.

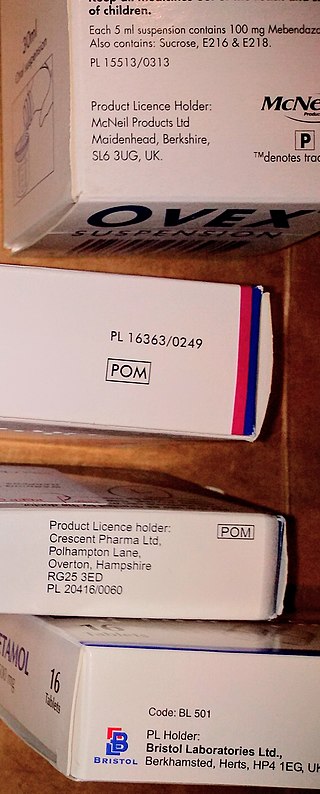

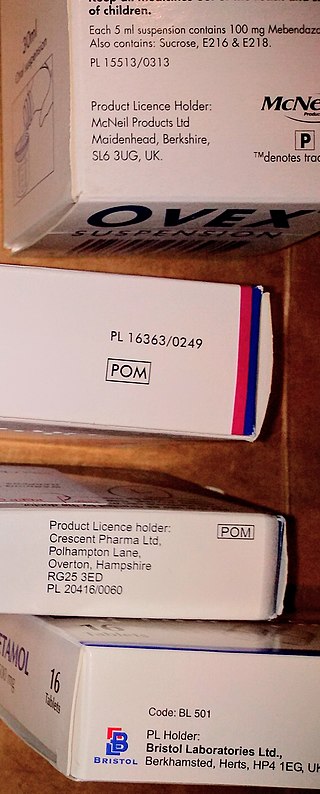

Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are medicines sold directly to a consumer without a requirement for a prescription from a healthcare professional, as opposed to prescription drugs, which may be supplied only to consumers possessing a valid prescription. In many countries, OTC drugs are selected by a regulatory agency to ensure that they contain ingredients that are safe and effective when used without a physician's care. OTC drugs are usually regulated according to their active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) rather than final products. By regulating APIs instead of specific drug formulations, governments allow manufacturers the freedom to formulate ingredients, or combinations of ingredients, into proprietary mixtures.

A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that is permitted to be dispensed only to those with a medical prescription. In contrast, over-the-counter drugs can be obtained without a prescription. The reason for this difference in substance control is the potential scope of misuse, from drug abuse to practicing medicine without a license and without sufficient education. Different jurisdictions have different definitions of what constitutes a prescription drug.

Pharmacovigilance, also known as drug safety, is the pharmaceutical science relating to the "collection, detection, assessment, monitoring, and prevention" of adverse effects with pharmaceutical products. The etymological roots for the word "pharmacovigilance" are: pharmakon and vigilare. As such, pharmacovigilance heavily focuses on adverse drug reactions (ADR), which are defined as any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended, including lack of efficacy. Medication errors such as overdose, and misuse and abuse of a drug as well as drug exposure during pregnancy and breastfeeding, are also of interest, even without an adverse event, because they may result in an adverse drug reaction.

The Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (SUSMP), also known as the Poisons Standard for short, is an Australian legislative instrument produced by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Before 2010, it was known as the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons (SUSDP). The SUSMP classifies drugs and poisons into different Schedules signifying the degree of control recommended to be exercised over their availability to the public. As of 2023, the most recent version is the Therapeutic Goods Instrument 2023.

The United Kingdom Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 aimed to control the possession and supply of numerous listed drugs and drug-like substances as a controlled substance. The act allowed and regulated the use of some Controlled Drugs by various classes of persons acting in their professional capacity.

An online pharmacy, internet pharmacy, or mail-order pharmacy is a pharmacy that operates over the Internet and sends orders to customers through mail, shipping companies, or online pharmacy web portal.

In the field of pharmacy, compounding is preparation of custom medications to fit unique needs of patients that cannot be met with mass-produced products. This may be done, for example, to provide medication in a form easier for a given patient to ingest, or to avoid a non-active ingredient a patient is allergic to, or to provide an exact dose that isn't otherwise available. This kind of patient-specific compounding, according to a prescriber's specifications, is referred to as "traditional" compounding. The nature of patient need for such customization can range from absolute necessity to individual optimality to even preference.

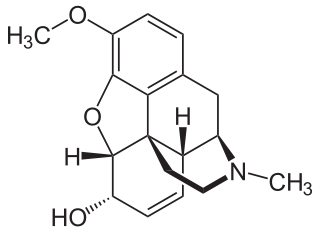

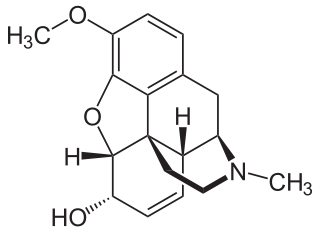

Codeine is an opiate and prodrug of morphine mainly used to treat pain, coughing, and diarrhea. It is also commonly used as a recreational drug. It is found naturally in the sap of the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum. It is typically used to treat mild to moderate degrees of pain. Greater benefit may occur when combined with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Evidence does not support its use for acute cough suppression in children or adults. In Europe, it is not recommended as a cough medicine in those under 12 years of age. It is generally taken by mouth. It typically starts working after half an hour, with maximum effect at two hours. Its effects last for about four to six hours. Codeine exhibits abuse potential similar to other opioid medications, including a risk of habituation and overdose.

Homeopathy is fairly common in some countries while being uncommon in others. In some countries, there are no specific legal regulations concerning the use of homeopathy, while in others, licenses or degrees in conventional medicine from accredited universities are required.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to clinical research:

Electronic Prescriptions for Controlled Substances (EPCS) was originally a proposal for the DEA to revise its regulations to provide practitioners with the option of writing electronic prescriptions for controlled substances. These regulations would also permit pharmacies to receive, dispense, and archive these electronic prescriptions. These proposed regulations would be an addition to, not a replacement of, the existing rule.

Because of the uncertain nature of various alternative therapies and the wide variety of claims different practitioners make, alternative medicine has been a source of vigorous debate, even over the definition of "alternative medicine". Dietary supplements, their ingredients, safety, and claims, are a continual source of controversy. In some cases, political issues, mainstream medicine and alternative medicine all collide, such as in cases where synthetic drugs are legal but the herbal sources of the same active chemical are banned.

Drug disposal is the discarding of drugs. Individuals commonly dispose of unused drugs that remain after the end of medical treatment. Health care organizations dispose of drugs on a larger scale for a range of reasons, including having leftover drugs after treating patients and discarding of expired drugs. Failure to properly dispose of drugs creates opportunities for others to take them inappropriately. Inappropriate disposal of drugs can also cause drug pollution.

The distribution of medications has special drug safety and security considerations. Some drugs require cold chain management in their distribution.

Consumer Health Laws are laws that ensure that health products are safe and effective and that health professionals are competent; that government agencies enforce the laws and keep the public informed; professional, voluntary, and business organizations that serve as consumer advocates, monitor government agencies that issue safety regulations, and provide trustworthy information about health products and services; education of the consumer to permit freedom of choice based on an understanding of scientific data rather than misleading information; action by individuals to register complaints when they have been deceived, misled, overcharged, or victimized by frauds.

Drug labelling is also referred to as prescription labelling, is a written, printed or graphic matter upon any drugs or any of its container, or accompanying such a drug. Drug labels seek to identify drug contents and to state specific instructions or warnings for administration, storage and disposal. Since 1800s, legislation has been advocated to stipulate the formats of drug labelling due to the demand for an equitable trading platform, the need of identification of toxins and the awareness of public health. Variations in healthcare system, drug incidents and commercial utilization may attribute to different regional or national drug label requirements. Despite the advancement in drug labelling, medication errors are partly associated with undesirable drug label formatting.

The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 is an Act of the Commonwealth of Australia which regulates therapeutic goods. The Act is administered by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which is part of the Commonwealth Department of Health. The statutory framework set out in the Act is supplemented by the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990 and the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 2002.