The European Convention on Human Rights is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953. All Council of Europe member states are party to the convention and new members are expected to ratify the convention at the earliest opportunity.

International human rights instruments are the treaties and other international texts that serve as legal sources for international human rights law and the protection of human rights in general. There are many varying types, but most can be classified into two broad categories: declarations, adopted by bodies such as the United Nations General Assembly, which are by nature declaratory, so not legally-binding although they may be politically authoritative and very well-respected soft law;, and often express guiding principles; and conventions that are multi-party treaties that are designed to become legally binding, usually include prescriptive and very specific language, and usually are concluded by a long procedure that frequently requires ratification by each states' legislature. Lesser known are some "recommendations" which are similar to conventions in being multilaterally agreed, yet cannot be ratified, and serve to set common standards. There may also be administrative guidelines that are agreed multilaterally by states, as well as the statutes of tribunals or other institutions. A specific prescription or principle from any of these various international instruments can, over time, attain the status of customary international law whether it is specifically accepted by a state or not, just because it is well-recognized and followed over a sufficiently long time.

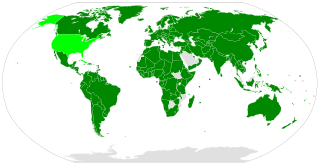

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights and rights to due process and a fair trial. It was adopted by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) on 16 December 1966 and entered into force on 23 March 1976 after its thirty-fifth ratification or accession. As of June 2022, the Covenant has 173 parties and six more signatories without ratification, most notably the People's Republic of China and Cuba; North Korea is the only state that has tried to withdraw.

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdictions and depends on the arrangements made between them. In addition to legal aspects of the process, extradition also involves the physical transfer of custody of the person being extradited to the legal authority of the requesting jurisdiction.

A fair trial is a trial which is "conducted fairly, justly, and with procedural regularity by an impartial judge". Various rights associated with a fair trial are explicitly proclaimed in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, and Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights, in addition to numerous other constitutions and declarations throughout the world. There is no binding international law that defines what is not a fair trial; for example, the right to a jury trial and other important procedures vary from nation to nation.

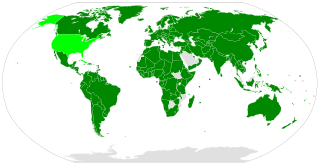

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of July 2020, the Covenant has 171 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

Fundamental rights are a group of rights that have been recognized by a high degree of protection from encroachment. These rights are specifically identified in a constitution, or have been found under due process of law. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 16, established in 2015, underscores the link between promoting human rights and sustaining peace.

Digital rights are those human rights and legal rights that allow individuals to access, use, create, and publish digital media or to access and use computers, other electronic devices, and telecommunications networks. The concept is particularly related to the protection and realization of existing rights, such as the right to privacy and freedom of expression, in the context of digital technologies, especially the Internet. The laws of several countries recognize a right to Internet access.

The right to property, or the right to own property, is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typically heavily constrained insofar as property is owned by legal persons and where it is used for production rather than consumption. The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is credited as a significant precedent for the legal protection of individual property rights.

The right to education has been recognized as a human right in a number of international conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which recognizes a right to free, primary education for all, an obligation to develop secondary education accessible to all with the progressive introduction of free secondary education, as well as an obligation to develop equitable access to higher education, ideally by the progressive introduction of free higher education. In 2021, 171 states were parties to the Covenant.

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, otherwise known as the European Convention on Bioethics or the European Bioethics Convention, is an international instrument aiming to prohibit the misuse of innovations in biomedicine and to protect human dignity. The Convention was opened for signature on 4 April 1997 in Oviedo, Spain and is thus otherwise known as the Oviedo Convention. The International treaty is a manifestation of the effort on the part of the Council of Europe to keep pace with developments in the field of biomedicine; it is notably the first multilateral binding instrument entirely devoted to biolaw. The Convention entered into force on 1 December 1999.

The margin of appreciation is a legal doctrine with a wide scope in international human rights law. It was developed by the European Court of Human Rights to judge whether a state party to the European Convention on Human Rights should be sanctioned for limiting the enjoyment of rights. The doctrine allows the court to reconcile practical differences in implementing the articles of the convention. Such differences create a limited right for contracting parties "to derogate from the obligations laid down in the Convention". The doctrine also reinforces the role of the European Convention as a supervisory framework for human rights. In applying that discretion, the court's judges must take into account differences between domestic laws of the contracting parties as they relate to substance and procedure. The margin of appreciation doctrine contains concepts that are analogous to the principle of subsidiarity, which occurs in the unrelated field of EU law. The purposes of the margin of appreciation are to balance individual rights with national interests and to resolve any potential conflicts. It has been suggested that the European Court should generally refer to the State's decision, as it is an international court, instead of a bill of rights.

Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights provides the right to freedom of expression and information. A fundamental aspect of this right is the freedom to hold opinions and receive and impart information and ideas, even if the receiver of such information does not share the same opinions or views as the provider.

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights provides a right to respect for one's "private and family life, his home and his correspondence", subject to certain restrictions that are "in accordance with law" and "necessary in a democratic society". The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international treaty to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe.

The Belgian Linguistic case (1968) 1 EHRR 252 is a formative case on the right to education under the European Convention of Human Rights, Protocol 1, art 2. It related to "certain aspects of the laws on the use of languages in education in Belgium", was decided by the European Court of Human Rights in 1968.

Demir and Baykara v Turkey [2008] ECHR 1345 is a landmark European Court of Human Rights case concerning Article 11 ECHR and the right to engage in collective bargaining. It affirmed the fundamental right of workers to engage in collective bargaining and take collective action to achieve that end.

Article 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) provides for two constituent rights: the right to marry and the right to found a family. With an explicit reference to ‘national laws governing the exercise of this right’, Article 12 raises issues as to the doctrine of the margin of appreciation, and the related principle of subsidiarity most prominent in European Union Law. It has most prominently been utilised, often alongside Article 8 of the Convention, to challenge the denial of same sex marriage in the domestic law of a Contracting state.

The right to sexuality incorporates the right to express one's sexuality and to be free from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Specifically, it relates to the human rights of people of diverse sexual orientations, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, and the protection of those rights, although it is equally applicable to heterosexuality. The right to sexuality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation is based on the universality of human rights and the inalienable nature of rights belonging to every person by virtue of being human.

The right to personal identity is recognised in international law through a range of declarations and conventions. From as early as birth, an individual's identity is formed and preserved by registration or being bestowed with a name. However, personal identity becomes more complex as an individual develops a conscience. But human rights exist to defend and protect individuality, as quoted by Law Professor Jill Marshall "Human rights law exist to ensure that individual lifestyle choices are protected from majoritarian or populist infringement." Despite the complexity of personal identity, it is preserved and encouraged through privacy, personality rights and the right to self-expression.

Media freedom in the European Union is a fundamental right that applies to all member states of the European Union and its citizens, as defined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as well as the European Convention on Human Rights. Within the EU enlargement process, guaranteeing media freedom is named a "key indicator of a country's readiness to become part of the EU".