Domitian was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavian dynasty. Described as "a ruthless but efficient autocrat", his authoritarian style of ruling put him at sharp odds with the Senate, whose powers he drastically curtailed.

Vespasian was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolidation of the empire generated political stability and a vast Roman building program.

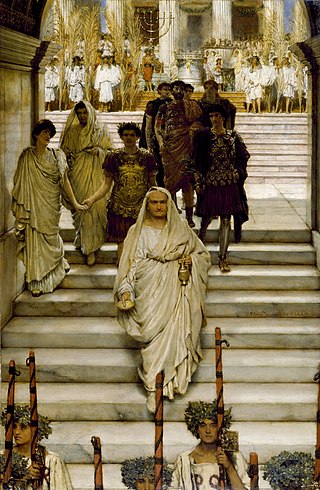

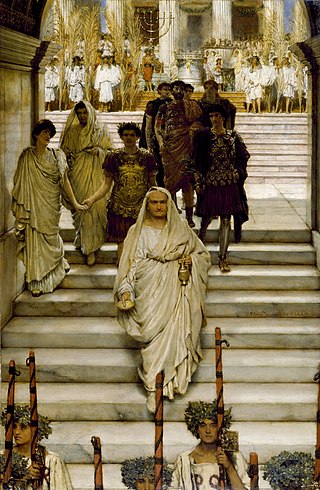

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or, in some historical traditions, one who had successfully completed a foreign war.

The Pax Romana is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a period and as a golden age of increased as well as sustained Roman imperialism, relative peace and order, prosperous stability, hegemonial power, and regional expansion, despite several revolts and wars, and continuing competition with Parthia. It is traditionally dated as commencing from the accession of Augustus, founder of the Roman principate, in 27 BC and concluding in 180 AD with the death of Marcus Aurelius, the last of the "Five Good Emperors". Since it was inaugurated by Augustus at the end of the final war of the Roman Republic, it is sometimes also called the Pax Augusta. During this period of about two centuries, the Roman Empire achieved its greatest territorial extent and its population reached a maximum of up to 70 million people. According to Cassius Dio, the dictatorial reign of Commodus, later followed by the Year of the Five Emperors and the Crisis of the Third Century, marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust".

Titus Caesar Vespasianus was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Rome:

In ancient Roman culture, felicitas is a condition of divinely inspired productivity, blessedness, or happiness. Felicitas could encompass both a woman's fertility and a general's luck or good fortune. The divine personification of Felicitas was cultivated as a goddess. Although felicitas may be translated as "good luck," and the goddess Felicitas shares some characteristics and attributes with Fortuna, the two were distinguished in Roman religion. Fortuna was unpredictable and her effects could be negative, as the existence of an altar to Mala Fortuna acknowledges. Felicitas, however, always had a positive significance. She appears with several epithets that focus on aspects of her divine power.

In ancient Roman religion, Spes was the goddess of hope. Multiple temples to Spes are known, and inscriptions indicate that she received private devotion as well as state cult.

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Roman emperor was the ruler and monarchial head of state of the Roman Empire during the imperial period. The emperors used a variety of different titles throughout history. Often when a given Roman is described as becoming "emperor" in English it reflects his taking of the title augustus. Another title often used was caesar, used for heirs-apparent, and imperator, originally a military honorific. Early emperors also used the title princeps civitatis. Emperors frequently amassed republican titles, notably princeps senatus, consul, and pontifex maximus.

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. It is considered an important interval, marking the transition from the Julio-Claudians, the first imperial dynasty, to the Flavian dynasty. The period witnessed several rebellions and claimants, with shifting allegiances and widespread turmoil in Rome and the provinces.

The Flavian dynasty ruled the Roman Empire between AD 69 and 96, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian (69–79), and his two sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96). The Flavians rose to power during the civil war of 69, known as the Year of the Four Emperors. After Galba and Otho died in quick succession, Vitellius became emperor in mid 69. His claim to the throne was quickly challenged by legions stationed in the Eastern provinces, who declared their commander Vespasian emperor in his place. The Second Battle of Bedriacum tilted the balance decisively in favour of the Flavian forces, who entered Rome on 20 December. The following day, the Roman Senate officially declared Vespasian emperor of the Roman Empire, thus commencing the Flavian dynasty. Although the dynasty proved to be short-lived, several significant historic, economic and military events took place during their reign.

In ancient Roman religion, a votum, plural vota, is a vow or promise made to a deity. The word comes from the past participle of the Latin verb voveo, vovere, "vow, promise". As the result of this verbal action, a votum is also that which fulfills a vow, that is, the thing promised, such as offerings, a statue, or even a temple building. The votum is thus an aspect of the contractual nature of Roman religion, a bargaining expressed by do ut des, "I give that you might give."

The Principate is the name sometimes given to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the so-called Dominate.

The Dominate, also known as the late Roman Empire, is the name sometimes given to the "despotic" later phase of imperial government in the ancient Roman Empire. It followed the earlier period known as the "Principate". Until the empire was reunited in 313, this phase is more often called the Tetrarchy.

The Roman imperial cult identified emperors and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority (auctoritas) of the Roman State. Its framework was based on Roman and Greek precedents, and was formulated during the early Principate of Augustus. It was rapidly established throughout the Empire and its provinces, with marked local variations in its reception and expression.

The Cancelleria Reliefs are a set of two incomplete bas-reliefs, believed to have been commissioned by the Roman Emperor Domitian. The reliefs originally depicted events from the life and reign of Domitian, but were partially recarved following the accession of emperor Nerva. They are now in the Vatican Museums.

Nerva was Roman emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor when aged almost 66, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the succeeding rulers of the Flavian dynasty. Under Nero, he was a member of the imperial entourage and played a vital part in exposing the Pisonian conspiracy of 65. Later, as a loyalist to the Flavians, he attained consulships in 71 and 90 during the reigns of Vespasian and Domitian, respectively. On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy involving members of the Praetorian Guard and several of his freedmen. On the same day, Nerva was declared emperor by the Roman Senate. As the new ruler of the Roman Empire, he vowed to restore liberties which had been curtailed during the autocratic government of Domitian.

The Stoic Opposition is the name given to a group of Stoic philosophers who actively opposed the autocratic rule of certain emperors in the 1st-century, particularly Nero and Domitian. Most prominent among them was Thrasea Paetus, an influential Roman senator executed by Nero. They were held in high regard by the later Stoics Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Thrasea, Rubellius Plautus and Barea Soranus were reputedly students of the famous Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus and as all three were executed by Nero they became known collectively as the Stoic martyrs.