Related Research Articles

A warp drive or a drive enabling space warp is a fictional superluminal spacecraft propulsion system in many science fiction works, most notably Star Trek, and a subject of ongoing physics research. The general concept of "warp drive" was introduced by John W. Campbell in his 1957 novel Islands of Space and was popularized by the Star Trek series. Its closest real-life equivalent is the Alcubierre drive, a theoretical solution of the field equations of general relativity.

Reginald Bretnor was an American science fiction author who flourished between the 1950s and 1980s. Most of his fiction was in short story form, and usually featured a whimsical story line or ironic plot twist. He also wrote on military theory and public affairs, and edited some of the earliest books to consider SF from a literary theory and criticism perspective.

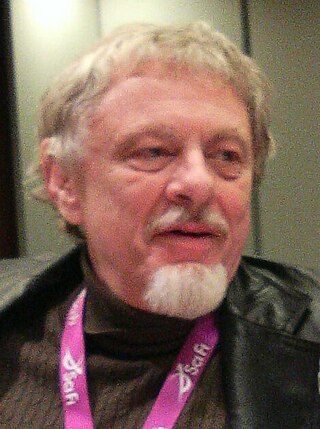

Norman Richard Spinrad is an American science fiction author, essayist, and critic. His fiction has won the Prix Apollo and been nominated for numerous awards, including the Hugo Award and multiple Nebula Awards.

A fantasy world or fictional world is a world created for fictional media, such as literature, film or games. Typical fantasy worlds feature magical abilities. Some worlds may be a parallel world connected to Earth via magical portals or items ; an imaginary universe hidden within ours ; a fictional Earth set in the remote past or future ; an alternative version of our History ; or an entirely independent world set in another part of the universe.

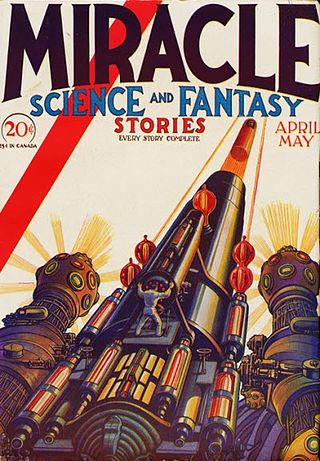

Science fantasy is a hybrid genre within speculative fiction that simultaneously draws upon or combines tropes and elements from both science fiction and fantasy. In a conventional science fiction story, the world is presented as being scientifically logical, while a conventional fantasy story contains mostly supernatural and artistic elements that disregard the scientific laws of the real world. The world of science fantasy, however, is laid out to be scientifically logical and often supplied with hard science-like explanations of any supernatural elements.

Asimov's Science Fiction is an American science fiction magazine edited by Sheila Williams and published by Dell Magazines, which is owned by Penny Press. It was launched as a quarterly by Davis Publications in 1977, after obtaining Isaac Asimov's consent for the use of his name. It was originally titled Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, and was quickly successful, reaching a circulation of over 100,000 within a year, and switching to monthly publication within a couple of years. George H. Scithers, the first editor, published many new writers who went on to be successful in the genre. Scithers favored traditional stories without sex or obscenity; along with frequent humorous stories, this gave Asimov's a reputation for printing juvenile fiction, despite its success. Asimov was not part of the editorial team, but wrote editorials for the magazine.

In science fiction, hyperspace is a concept relating to higher dimensions as well as parallel universes and a faster-than-light (FTL) method of interstellar travel. Its use in science fiction originated in the magazine Amazing Stories Quarterly in 1931 and within several decades it became one of the most popular tropes of science fiction, popularized by its use in the works of authors such as Isaac Asimov and E. C. Tubb, and media franchises such as Star Wars.

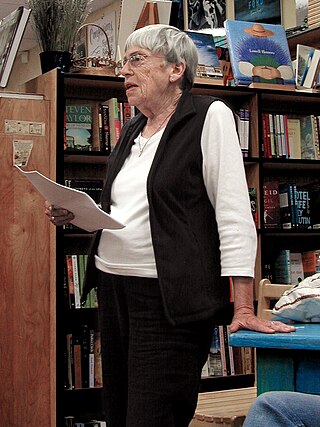

Vonda Neel McIntyre was an American science fiction writer and biologist.

The exploration of politics in science fiction is arguably older than the identification of the genre. One of the earliest works of modern science fiction, H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, is an extrapolation of the class structure of the United Kingdom of his time, an extreme form of social Darwinism; during tens of thousands of years, human beings have evolved into two different species based on their social class.

Worldbuilding is the process of constructing a world, originally an imaginary one, sometimes associated with a fictional universe. Developing an imaginary setting with coherent qualities such as a history, geography, and ecology is a key task for many science fiction or fantasy writers. Worldbuilding often involves the creation of geography, a backstory, flora, fauna, inhabitants, technology and often if writing speculative fiction, different peoples. This may include social customs as well as invented languages for the world.

Gordon Eklund is an American science fiction author whose works include the "Lord Tedric" series and two of the earliest original novels based on the 1960s Star Trek TV series. He has written under the pen name Wendell Stewart, and in one instance under the name of the late E. E. "Doc" Smith.

There have been many attempts at defining science fiction. This is a list of definitions that have been offered by authors, editors, critics and fans over the years since science fiction became a genre. Definitions of related terms such as "science fantasy", "speculative fiction", and "fabulation" are included where they are intended as definitions of aspects of science fiction or because they illuminate related definitions—see e.g. Robert Scholes's definitions of "fabulation" and "structural fabulation" below. Some definitions of sub-types of science fiction are included, too; for example see David Ketterer's definition of "philosophically-oriented science fiction". In addition, some definitions are included that define, for example, a science fiction story, rather than science fiction itself, since these also illuminate an underlying definition of science fiction.

Black holes, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing including light can escape them, have been depicted in fiction since before the term was coined by John Archibald Wheeler in the late 1960s. Black holes have been depicted with varying degrees of accuracy to the scientific understanding of them. Because what lies beyond the event horizon is unknown and by definition unobservable from outside, authors have been free to employ artistic license when depicting the interiors of black holes.

The Ascent of Wonder: The Evolution of Hard SF is a definitive 1994 anthology of hard science fiction (sf) short stories compiled by the award-winning editing team of David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer. This 990-page book includes 68 stories, each prefaced by a brief note to describe facts about the author, related works, or the logic of the story's inclusion in the genre. In addition, the book opens with three essays about the meaning and the boundaries of hard science fiction. The editors further explored these issues in The Hard SF Renaissance (2002).

Soft science fiction, or soft SF, is a category of science fiction with two different definitions, defined in contrast to hard science fiction. It can refer to science fiction that explores the "soft" sciences, as opposed to hard science fiction, which explores the "hard" sciences. It can also refer to science fiction which prioritizes human emotions over the scientific accuracy or plausibility of hard science fiction.

Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, An English-Language Selection, 1949–1984 is a nonfiction book by David Pringle, published by Xanadu in 1985 with a foreword by Michael Moorcock. Primarily, the book comprises 100 short essays on the selected works, covered in order of publication, without any ranking. It is considered an important critical summary of the science fiction field.

Full Spectrum is a series of five anthologies of fantasy and science fiction short stories published between 1988 and 1995 by Bantam Spectra. The first anthology was edited by Lou Aronica and Shawna McCarthy; the second by Aronica, McCarthy, Amy Stout, and Pat LoBrutto; the third and fourth by Aronica, Stout, and Betsy Mitchell; and the fifth by Jennifer Hershey, Tom Dupree, and Janna Silverstein.

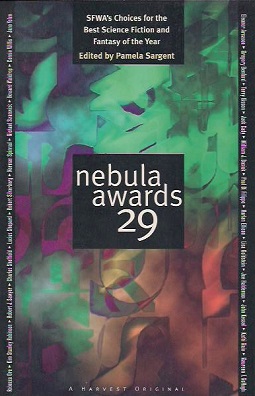

Nebula Awards 29 is an anthology of award-winning science fiction short works edited by Pamela Sargent, the first of three successive volumes under her editorship. It was first published in hardcover and trade paperback by Harcourt Brace in April 1995.

Space travel, or space flight is a classic science-fiction theme that has captivated the public and is almost archetypal for science fiction. Space travel, interplanetary or interstellar, is usually performed in space ships, and spacecraft propulsion in various works ranges from the scientifically plausible to the totally fictitious.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Spinrad, Norman (1976). "Rubber Sciences". In Reginald Bretnor (ed.). The Craft of Science Fiction . New York: Harper & Row. pp. 54–69. ISBN 0060104619.

- ↑ Spinrad, Norman (September 9, 2010). A Critic at Large in the Multiverse. Norman Spinrad. p. 22. ASIN B0042JT3MQ.

- ↑ Benford, Gregory (1989-01-29). "Rubber Science, Real Science and Science Fiction". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 2011-05-26.

- ↑ McIntyre, Vonda N. (1981). "The Straining Your Eyes Through the Viewscreen Blue". In Herbert, Frank (ed.). Nebula Winners Fifteen. Harper & Row. p. 81. ISBN 0-06-01-4830-6.

- ↑ Scithers, George H.; Schweitzer, Darrell; Ford, John M. (1981). "Science: The Art of Knowing". On Writing Science Fiction. Owlswick Press. p. 141. ISBN 0913896195.

- ↑ Anderson, Poul (April–June 1979). Baen, James (ed.). "On Imaginary Science". Destinies. Ace Books. 1 (3): 310–313.

- ↑ Henderson, C. J. (2001). "Buck Rogers in the 25th Century". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies. Checkmark Books. p. 52. ISBN 0-8160-4043-5.

- 1 2 Bischoff, David (February 1995). "Star trek: Voyager". Omni . 17 (5): 82.

- ↑ Peter Coogan; Randy Duncan & Kate McClancy (Winter 2009). "The CAC Report". Comic-Con Magazine : 22. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Bliss, Pam (April 12, 2010). "Hopelessly Lost, But Making Good Time #108". Sequential Tart. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Long, Steven S. (2006). "Chapter Two: The Skills". The Ultimate Skill. Hero Games. pp. 259, 267. ISBN 1-58366-098-4.

- ↑ Friedrich, Brionna (May 12, 2013). ""What if?" Sci-fi and poetry natural to Grayland writer". The Daily World . Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Shepard, Lucius (2010). "A Letter from Lucius Shepard". In Damien Broderick (ed.). Skiffy and Mimesis: More Best of Australian SF Review (Second Series). Borgo Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1434457875.

- ↑ Crispin, A.C. (May 5, 2011). "The Wall Comes Down in Space: Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country". Tor.com . Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Cramer, John G. (1989). "Afterword". Twistor . Avon Books. pp. 332–333. ISBN 0-380-71027-7.

- ↑ "The Uprising". Kirkus Reviews . LXXXI (12). June 15, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Benford, Gregory (1996). "In the Wake of the Wave". In George Edgar Slusser; Gary Westfahl; Eric S. Rabkin (eds.). Science Fiction and Market Realities. University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ "The Bar Code Prophecy". Kirkus Reviews . LXXX (20). October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Suillivan, Tim (September 29, 1991). "Worlds Without End". The Washington Post .