Eskimo is an exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit and the Yupik of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the Aleut, who inhabit the Aleutian Islands, are generally excluded from the definition of Eskimo. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the family of Eskaleut languages.

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and the adjacent subarctic regions as far south as Labrador. The Inuit languages are one of the two branches of the Eskimoan language family, the other being the Yupik languages, which are spoken in Alaska and the Russian Far East. Most Inuit people live in one of three countries: Greenland, a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark; Canada, specifically in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories, the Nunavik region of Quebec, and the Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut regions of Labrador; and the United States, specifically in northern and western Alaska.

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation "Thule" originates from the location of Thule in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer's Midden.

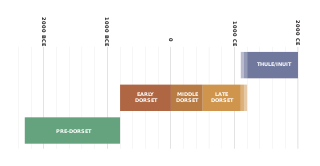

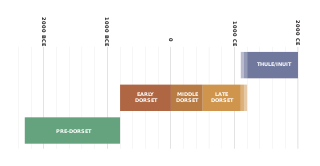

The Paleo-Eskimo were the peoples who inhabited the Arctic region from Chukotka in present-day Russia across North America to Greenland prior to the arrival of the modern Inuit (Eskimo) and related cultures. The first known Paleo-Eskimo cultures developed by 2500 BCE, but were gradually displaced in most of the region, with the last one, the Dorset culture, disappearing around 1500 CE.

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BCE to between 1000 CE and 1500 CE, that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset in Nunavut, Canada, where the first evidence of its existence was found. The culture has been defined as having four phases due to the distinct differences in the technologies relating to hunting and tool making. Artifacts include distinctive triangular end-blades, oil lamps made of soapstone, and burins.

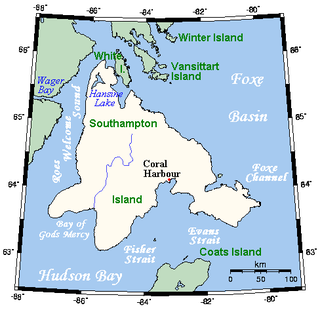

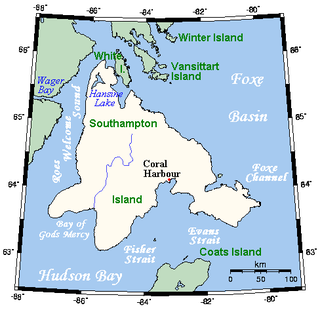

Southampton Island is a large island at the entrance to Hudson Bay at Foxe Basin. One of the larger members of the Arctic Archipelago, Southampton Island is part of the Kivalliq Region in Nunavut, Canada. The area of the island is stated as 41,214 km2 (15,913 sq mi) by Statistics Canada. It is the 34th largest island in the world and Canada's ninth largest island. The only settlement on Southampton Island is Coral Harbour, called Salliq in Inuktitut.

The Saqqaq culture was a Paleo-Eskimo culture in southern Greenland. Up to this day, no other people seem to have lived in Greenland continually for as long as the Saqqaq.

The Birnirk culture was a prehistoric Inuit culture of the north coast of Alaska, dating from the sixth century A.D. to the twelfth century A.D. The Birnirk culture first appeared on the American side of the Bering Strait, descending from the Old Bering Sea/Okvik culture and preceding the Thule culture; it is distinguished by its advanced harpoon and marine technology. A burial mound of the Birnirk culture was discovered in the town of Wales, Alaska; 16 more have been found in Utqiagvik at the "Birnirk site," which is now a National Historic Landmark. An ancient Birnirk village has been found at present-day Ukpiaġvik.

Coats Island lies at the northern end of Hudson Bay in the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut. At 5,498 km2 (2,123 sq mi) in size, it is the 107th largest island in the world, and Canada's 24th largest island.

Coral Harbour is a small Inuit community that is located on Southampton Island, Kivalliq Region, in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. Its name is derived from the fossilized coral that can be found around the waters of the community which is situated at the head of South Bay. The name of the settlement in Inuktitut is Salliq, sometimes used to refer to all of Southampton Island. The plural Salliit, means large flat island(s) in front of the mainland.

The history of Nunavut covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Eskimo thousands of years ago to present day. Prior to the colonization of the continent by Europeans, the lands encompassing present-day Nunavut were inhabited by several historical cultural groups, including the Pre-Dorset, the Dorsets, the Thule and their descendants, the Inuit.

The Inughuit, or the Smith Sound Inuit, historically Arctic Highlanders or Polar Eskimos, are Greenlandic Inuit. They are the northernmost group of Inuit and the northernmost people in North America, living in Greenland. Inughuit make up about 1% of the population of Greenland.

Circumpolar peoples and Arctic peoples are umbrella terms for the various indigenous peoples of the Arctic region.

Inuit are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon (traditionally), Alaska, and Chukotsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut languages, also known as Inuit-Yupik-Unangan, and also as Eskaleut. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

The Inuit are an indigenous people of the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America. The ancestors of the present-day Inuit are culturally related to Iñupiat, and Yupik, and the Aleut who live in the Aleutian Islands of Siberia and Alaska. The term culture of the Inuit, therefore, refers primarily to these areas; however, parallels to other Eskimo groups can also be drawn.

Dorset Island or Cape Dorset Island is one of the Canadian Arctic islands located in Hudson Strait, Nunavut, Canada. It lies off the Foxe Peninsula area of southwestern Baffin Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region. It is serviced by an airport and a harbour.

The Pre-Dorset is a loosely defined term for a Paleo-Eskimo culture or group of cultures that existed in the Eastern Canadian Arctic from c. 3200 to 850 cal BC, and preceded the Dorset culture.

Native Point is a peninsula in the Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located on Southampton Island's Bell Peninsula at the mouth of Native Bay. It is notable for being the location of an abandoned Sadlermiut settlement, currently an archaeological site.

The following is an alphabetical list of topics related to Indigenous peoples in Canada, comprising the First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples.

The Greenlandic Inuit are the indigenous and most populous ethnic group in Greenland. Most speak Greenlandic and consider themselves ethnically Greenlandic. People of Greenland are citizens of Denmark.