Johann Gottlieb Fichte was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kant. Recently, philosophers and scholars have begun to appreciate Fichte as an important philosopher in his own right due to his original insights into the nature of self-consciousness or self-awareness. Fichte was also the originator of thesis–antithesis–synthesis, an idea that is often erroneously attributed to Hegel. Like Descartes and Kant before him, Fichte was motivated by the problem of subjectivity and consciousness. Fichte also wrote works of political philosophy; he has a reputation as one of the fathers of German nationalism.

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber was a German sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sciences more generally. His ideas continue to influence social theory and research.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, later von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him between Johann Gottlieb Fichte, his mentor in his early years, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, his one-time university roommate, early friend, and later rival. Interpreting Schelling's philosophy is regarded as difficult because of its evolving nature.

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional Protestant Christianity. He also became influential in the evolution of higher criticism, and his work forms part of the foundation of the modern field of hermeneutics. Because of his profound effect on subsequent Christian thought, he is often called the "Father of Modern Liberal Theology" and is considered an early leader in liberal Christianity. The neo-orthodoxy movement of the twentieth century, typically seen to be spearheaded by Karl Barth, was in many ways an attempt to challenge his influence. As a philosopher he was a leader of German Romanticism. Schleiermacher is considered the most important Protestant theologian between John Calvin and Karl Barth.

Friedrich Carl von Savigny was a German jurist and historian.

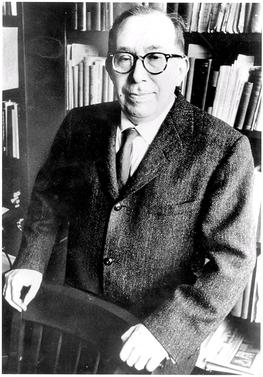

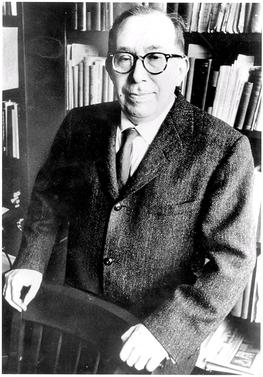

Leo Strauss was an American scholar of political philosophy. Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Strauss later emigrated from Germany to the United States. He spent much of his career as a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, where he taught several generations of students and published fifteen books.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is a book written by Max Weber, a German sociologist, economist, and politician. It began as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and '05, and was translated into English for the first time by American sociologist Talcott Parsons in 1930. It is considered a founding text in economic sociology and a milestone contribution to sociological thought in general.

"Politics as a Vocation" is an essay by German economist and sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920). It originated in the second lecture of a series he gave in Munich to the "Free Students Union" of Bavaria on 28 January 1919. This happened during the German Revolution when Munich itself was briefly the capital of the Bavarian Socialist Republic. Weber gave the speech based on handwritten notes which were transcribed by a stenographer. The essay was published in an extended version in July 1919, and translated into English only after World War II. The essay is today regarded as a classic work of political science and sociology.

Hans Adolf Eduard Driesch was a German biologist and philosopher from Bad Kreuznach. He is most noted for his early experimental work in embryology and for his neo-vitalist philosophy of entelechy. He has also been credited with performing the first artificial 'cloning' of an animal in the 1880s, although this claim is dependent on how one defines cloning.

The German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) distinguished three ideal types of legitimate political leadership/domination/authority . He wrote about these three types of domination both in his essay "The Three Types of Legitimate Rule", which was published in his 1921 masterwork Economy and Society, and in his classic 1919 speech "Politics as a Vocation" :

- charismatic authority,

- traditional authority and

- rational-legal authority.

This is a chronological list of works by Max Weber. Original titles with dates of publication and translated titles are given when possible, then a list of works translated into English, with earliest-found date of translation. The list of translations is most likely incomplete.

The fact–value distinction is a fundamental epistemological distinction described between:

- Statements of fact, which are based upon reason and observation, and examined via the empirical method.

- Statements of value, which encompass ethics and aesthetics, and are studied via axiology.

Hans Albert was a German philosopher. He was professor of social sciences at the University of Mannheim from 1963, and remained at the university until 1989. His fields of research were social sciences and general studies of methods. He was a critical rationalist, paying special attention to rational heuristics. Albert was a strong critic of the continental hermeneutic tradition coming from Heidegger and Gadamer.

Albin Alfred Baeumler, was an Austrian-born German philosopher, pedagogue and prominent Nazi ideologue. From 1924 he taught at the Technische Universität Dresden, at first as an unsalaried lecturer Privatdozent. Bäumler was made associate professor (Extraordinarius) in 1928 and full professor (Ordinarius) a year later. From 1933 he taught philosophy and political education in Berlin as the director of the Institute for Political Pedagogy.

The ethic of ultimate ends, moral conviction, or conviction is a concept in the moral philosophy of Max Weber, in which individuals act in a faithful, rather than rational, manner.

We must be clear about the fact that all ethically oriented conduct may be guided by one of two fundamentally differing and irreconcilably opposed maxims: conduct can be oriented to an "ethic of ultimate ends" or to an "ethic of responsibility." This is not to say that an ethic of ultimate ends is identical with irresponsibility, or that an ethic of responsibility is identical with unprincipled opportunism. Naturally, nobody says that. However, there is an abysmal contrast between conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of ultimate ends—that, is in religious terms, "the Christian does rightly and leaves the results with the Lord"—and conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of responsibility, in which case one has to give an account of the foreseeable results of one's action."

The following list of works by German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831).

Ludger Kühnhardt, born 4 June 1958 in Münster is a German political scientist, journalist and political advisor. From 1991 until 1997, he was Professor of Political Science at the University of Freiburg and from 1997 until his retirement in July 2024 Director at the Center for European Integration Studies (ZEI) and Professor at the Institute for Political Science and Sociology at the University of Bonn.

Wolf Joachim Singer is a German neurophysiologist.

Franz Schnabel was a German historian. He wrote about German history, particularly the "cultural crisis" of the 19th century in Germany as well as humanism after the end of the Third Reich. He opposed Nazism during the Second World War.

Theodor Litt was a German culture and social philosopher as well as a pedagogue.