Related Research Articles

Archaeopteryx, sometimes referred to by its German name, "Urvogel", is a genus of avian dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaīos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptéryx), meaning "feather" or "wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, Archaeopteryx was generally accepted by palaeontologists and popular reference books as the oldest known bird. Older potential avialans have since been identified, including Anchiornis, Xiaotingia, and Aurornis.

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves, characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight skeleton. Birds live worldwide and range in size from the 5.5 cm (2.2 in) bee hummingbird to the 2.8 m common ostrich. There are about ten thousand living species, more than half of which are passerine, or "perching" birds. Birds have wings whose development varies according to species; the only known groups without wings are the extinct moa and elephant birds. Wings, which are modified forelimbs, gave birds the ability to fly, although further evolution has led to the loss of flight in some birds, including ratites, penguins, and diverse endemic island species. The digestive and respiratory systems of birds are also uniquely adapted for flight. Some bird species of aquatic environments, particularly seabirds and some waterbirds, have further evolved for swimming. The study of birds is called ornithology.

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is a subject of active research. They became the dominant terrestrial vertebrates after the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event 201.3 mya and their dominance continued throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. The fossil record shows that birds are feathered dinosaurs, having evolved from earlier theropods during the Late Jurassic epoch, and are the only dinosaur lineage known to have survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 mya. Dinosaurs can therefore be divided into avian dinosaurs—birds—and the extinct non-avian dinosaurs, which are all dinosaurs other than birds.

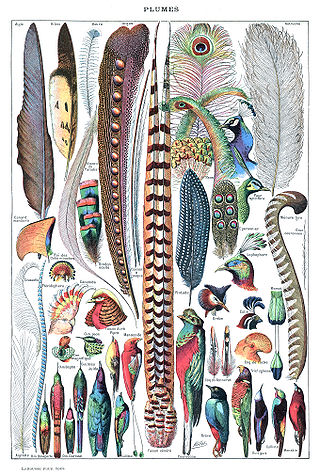

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premier example of a complex evolutionary novelty. They are among the characteristics that distinguish the extant birds from other living groups.

A feathered dinosaur is any species of dinosaur possessing feathers. That includes all species of birds, but there is a hypothesis that many, if not all non-avian dinosaur species also possessed feathers in some shape or form. That theory has been challenged by some research.

The evolution of birds began in the Jurassic Period, with the earliest birds derived from a clade of theropod dinosaurs named Paraves. Birds are categorized as a biological class, Aves. For more than a century, the small theropod dinosaur Archaeopteryx lithographica from the Late Jurassic period was considered to have been the earliest bird. Modern phylogenies place birds in the dinosaur clade Theropoda. According to the current consensus, Aves and a sister group, the order Crocodilia, together are the sole living members of an unranked reptile clade, the Archosauria. Four distinct lineages of bird survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, giving rise to ostriches and relatives (Palaeognathae), waterfowl (Anseriformes), ground-living fowl (Galliformes), and "modern birds" (Neoaves).

Waimanu is a genus of early penguin which lived during the Paleocene, soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, around 62–60 million years ago. It was about the size of an emperor penguin. It is one of the most important bird fossils for understanding the origin and evolution of birds because of the time period it comes from, and the position of penguins near the base of the bird family tree.

The scientific question of within which larger group of animals birds evolved has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated during the Mesozoic Era.

Around 350 BCE, Aristotle and other philosophers of the time attempted to explain the aerodynamics of avian flight. Even after the discovery of the ancestral bird Archaeopteryx which lived over 150 million years ago, debates still persist regarding the evolution of flight. There are three leading hypotheses pertaining to avian flight: Pouncing Proavis model, Cursorial model, and Arboreal model.

John Alan Feduccia is a paleornithologist specializing in the origins and phylogeny of birds. He is S. K. Heninger Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina. Feduccia's authored works include three major books, The Age of Birds, The Origin and Evolution of Birds, Riddle of the Feathered Dragons, and many peer-reviewed papers in ornithological and biological journals.

Neoaves is a clade that consists of all modern birds with the exception of Palaeognathae and Galloanserae. Almost 95% of the roughly 10,000 known species of extant birds belong to the Neoaves.

Aequornithes, or core water birds, are defined as "the least inclusive clade containing Gaviidae and Phalacrocoracidae".

Pennaraptora is a clade defined as the most recent common ancestor of Oviraptor philoceratops, Deinonychus antirrhopus, and Passer domesticus, and all descendants thereof, by Foth et al., 2014.

Eucavitaves is a clade that contains the order Trogoniformes (trogons) and the clade Picocoraciae. The name refers to the fact that the majority of them nest in cavities.

Cavitaves is a clade that contain the order Leptosomiformes and the clade Eucavitaves. The name refers to the fact that the majority of them nest in cavities.

Picocoraciae is a clade that contains the order Bucerotiformes and the clade Picodynastornithes supported by various genetic analysis and morphological studies. While these studies supported a sister grouping of Coraciiformes and Piciformes, a large scale, sparse supermatrix has suggested alternative sister relationship between Bucerotiformes and Piciformes instead.

Columbimorphae is a clade discovered by genome analysis that includes birds of the orders Columbiformes, Pterocliformes (sandgrouse), and Mesitornithiformes (mesites). Previous analyses had also recovered this grouping, although the exact relationships differed. Some studies indicated a sister relationship between sandgrouse and pigeons while other studies favored a sister grouping of mesites and sandgrouse instead.

Picodynastornithes is a clade that contains the orders Coraciiformes and Piciformes. This grouping also has current and historical support from molecular and morphological studies.

David P. Mindell is an American evolutionary biologist and author. He is currently a senior researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Mindell's work is focused on the systematics, conservation and molecular evolution of birds, especially birds of prey. He is known for his 2006 book, The Evolving World in which he explained, for the general public, how evolution applies to everyday life.

Mary J. O'Connell is an evolutionary genomicist and Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham. She is the Principal Investigator of the Computational & Molecular Evolutionary Biology Group in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham.

References

- 1 2 3 Edwards, Scott V. "Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Edwards Laboratory. Harvard University. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ↑ Edwards, Scott V. "Scott V. Edwards". Edwards Laboratory. Harvard University. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- 1 2 Kacoyanis, Stephanie (May 5, 2015). "Harvard faculty elected to NAS". Harvard Gazette. Harvard University. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Two Black Scholars Elected Members of the National Academy of Sciences". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ↑ Parks, Clinton (May 12, 2006). "Directing Minorities Toward Careers in Evolutionary Biology". Science Careers. Science. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ↑ Parker, Mary (March 19, 2013). "Scott Edwards' job is for the birds". Member Spotlight. AAAS MemberCentral. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ↑ "The American Philosophical Society Welcomes New Members for 2020".

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (November 20, 2014). "Your Inner Feather – Phenomena: The Loom". Phenomena: The Loom. National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ Lowe, Craig B.; Clarke, Julia A.; Baker, Allan J.; Haussler, David; Edwards, Scott V. (January 1, 2015). "Feather Development Genes and Associated Regulatory Innovation Predate the Origin of Dinosauria". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu309. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 4271537 . PMID 25415961.

- ↑ Bradt, Steve (March 8, 2007). "Despite their heft, many dinosaurs had surprisingly tiny genomes". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ Organ, Chris L.; Shedlock, Andrew M.; Meade, Andrew; Pagel, Mark; Edwards, Scott V. (March 8, 2007). "Origin of avian genome size and structure in non-avian dinosaurs". Nature. 446 (7132): 180–184. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..180O. doi:10.1038/nature05621. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17344851. S2CID 3031794.

- ↑ Edwards, Scott V.; Shultz, Allison J.; Campbell-Staton, Shane C. (2015). "Next-generation sequencing and the expanding domain of phylogeography". Folia Zoologica. 64 (3): 187–206. doi:10.25225/fozo.v64.i3.a2.2015. ISSN 0139-7893. S2CID 27832022.

- ↑ Liu, Liang; Anderson, Christian; Pearl, Dennis; Edwards, Scott V. (2019). "Modern Phylogenomics: Building Phylogenetic Trees Using the Multispecies Coalescent Model". Evolutionary Genomics. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1910. pp. 211–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9074-0_7 . ISBN 978-1-4939-9073-3. ISSN 1064-3745. PMID 31278666.

- ↑ Zhang, Guojie; Jarvis, Erich D.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (December 12, 2014). "A flock of genomes". Science. 346 (6215): 1308–1309. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1308Z. doi:10.1126/science.346.6215.1308. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4407557 . PMID 25504710.

- ↑ "Avian Phylogenomics Project". avian.genomics.cn. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ Lewin, Harris A.; Robinson, Gene E.; Kress, W. John; Baker, William J.; Coddington, Jonathan; Crandall, Keith A.; Durbin, Richard; Edwards, Scott V.; Forest, Félix; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Goldstein, Melissa M.; Grigoriev, Igor V.; Hackett, Kevin J.; Haussler, David; Jarvis, Erich D.; Johnson, Warren E.; Patrinos, Aristides; Richards, Stephen; Castilla-Rubio, Juan Carlos; van Sluys, Marie-Anne; Soltis, Pamela S.; Xu, Xun; Yang, Huanming; Zhang, Guojie (2018). "Earth BioGenome Project: Sequencing life for the future of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (17): 4325–4333. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.4325L. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720115115 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5924910 . PMID 29686065.

- ↑ Cook, Joseph A.; Edwards, Scott V.; Lacey, Eileen A.; Guralnick, Robert P.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Welch, Corey K.; Bell, Kayce C.; Galbreath, Kurt E. (August 1, 2014). "Natural History Collections as Emerging Resources for Innovative Education". BioScience. 64 (8): 725–734. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu096 . ISSN 0006-3568.

- ↑ "RCN-UBE: Advancing Integration of Museums into Undergraduate Programs (AIM-UP!)". National Science Foundation. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ↑ Maxwell Braun, David (November 3, 2008). "Rare Early Audubon Drawings Published for First Time". Voices: Ideas and Insight from Explorers. National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ Rosen, Jonathan (December 7, 2008). "Audubon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved May 27, 2015.