The influence and imperialism of Western Europe and associated states peaked in Asian territories from the colonial period beginning in the 16th century and substantially reducing with 20th century decolonization. It originated in the 15th-century search for trade routes to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia that led directly to the Age of Discovery, and additionally the introduction of early modern warfare into what Europeans first called the East Indies and later the Far East. By the early 16th century, the Age of Sail greatly expanded Western European influence and development of the spice trade under colonialism. European-style colonial empires and imperialism operated in Asia throughout six centuries of colonialism, formally ending with the independence of the Portuguese Empire's last colony Macau in 1999. The empires introduced Western concepts of nation and the multinational state. This article attempts to outline the consequent development of the Western concept of the nation state.

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, a group known as the "Boxers" in English due to many of its members having practised Chinese martial arts, which at the time were referred to as "Chinese boxing". It was defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance of foreign powers.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki, also known as the Treaty of Maguan in China and Treaty of Bakan in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was an unequal treaty signed at the Shunpanrō hotel, Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the First Sino-Japanese War.

Treaty ports were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan.

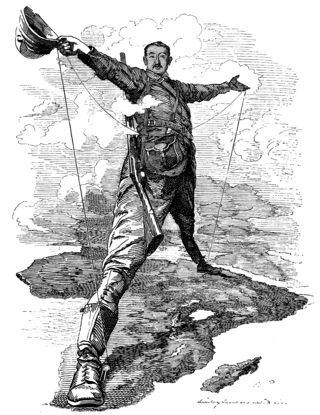

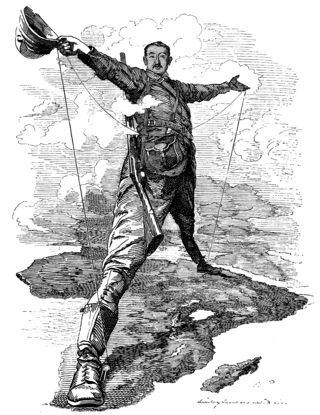

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of overseas territorial acquisitions. At the time, states focused on building their empires with new technological advances and developments, expanding their territory through conquest, and exploiting the resources of the subjugated countries. During the era of New Imperialism, the European powers individually conquered almost all of Africa and parts of Asia. The new wave of imperialism reflected ongoing rivalries among the great powers, the economic desire for new resources and markets, and a "civilizing mission" ethos. Many of the colonies established during this era gained independence during the era of decolonization that followed World War II.

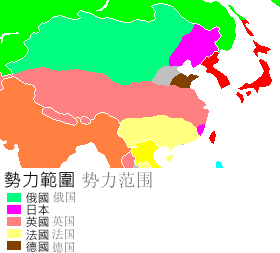

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

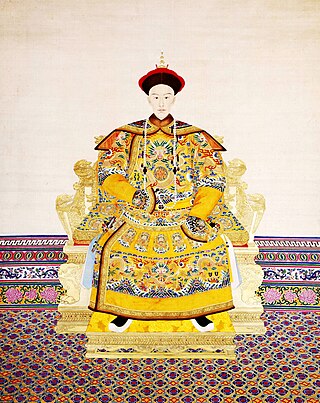

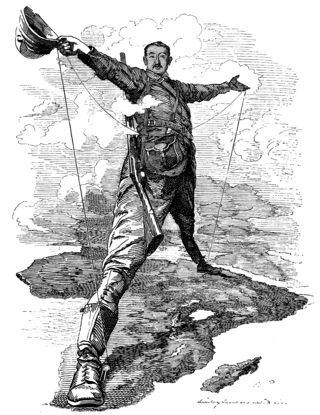

The Guangxu Emperor, also known by his temple name Emperor Dezong of Qing, personal name Zaitian, was the tenth emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign, which lasted from 1875 to 1908, was largely dominated by his aunt Empress Dowager Cixi. Guangxu initiated the radical Hundred Days' Reform but was abruptly stopped when the empress dowager launched a coup in 1898, after which he was held under virtual house arrest until his death.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, met on 15 November 1884, and after an adjournment concluded on 26 February 1885, with the signature of a General Act, regulating the European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period.

The Twenty-One Demands was a set of demands made during the First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the government of the Republic of China on 18 January 1915. The secret demands would greatly extend Japanese control of China. Japan would keep the former German areas it had conquered at the start of World War I in 1914. Japan would be strong in Manchuria and South Mongolia. And, Japan would have an expanded role in railways. The most extreme demands would give Japan a decisive voice in finance, policing, and government affairs. The last part would make China in effect a protectorate of Japan, and thereby reduce Western influence.

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several unequal treaties signed at Tianjin in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and the United States were the parties involved. These treaties, counted by the Chinese among the unequal treaties, opened more Chinese ports to foreign trade, permitted foreign legations in the Chinese capital Beijing, allowed Christian missionary activity, and effectively legalized the import of opium. They ended the first phase of the Second Opium War, which had begun in 1856 and were ratified by the Emperor of China in the Convention of Peking in 1860, after the end of the war.

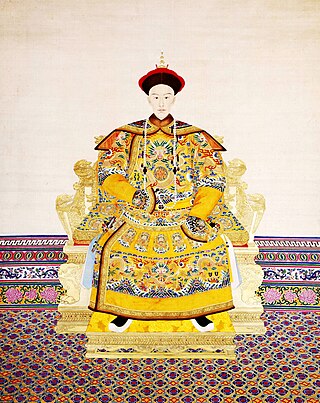

The Open Door Policy is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy was created in U.S. Secretary of State John Hay's Open Door Note, dated September 6, 1899, and circulated to the major European powers. In order to prevent the "carving of China like a melon", as they were doing in Africa, the Note asked the powers to keep China open to trade with all countries on an equal basis and called upon all powers, within their spheres of influence to refrain from interfering with any treaty port or any vested interest, to permit Chinese authorities to collect tariffs on an equal basis, and to show no favors to their own nationals in the matter of harbor dues or railroad charges. The policy was accepted only grudgingly, if at all, by the major powers, and it had no legal standing or enforcement mechanism. In July 1900, as the powers contemplated intervention to put down the violently anti-foreign Boxer uprising, Hay circulated a Second Open Door Note affirming the principles. Over the next decades, American policy-makers and national figures continued to refer to the Open Door Policy as a basic doctrine, and Chinese diplomats appealed to it as they sought American support, but critics pointed out that the policy had little practical effect.

Unequal treaties refer to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China and various foreign powers. The agreements, often reached after a military defeat or a threat of military invasion, contained one-sided terms, requiring China to cede land, pay reparations, open treaty ports, give up tariff autonomy, legalise opium import, and grant extraterritorial privileges to foreign citizens.

The Nine-Power Treaty or Nine-Power Agreement was a 1922 treaty affirming the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of China as per the Open Door Policy. The Nine-Power Treaty was signed on 6 February 1922 by all of the attendees to the Washington Naval Conference: Belgium, China, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United States.

During the Meiji period, the new Government of Meiji Japan also modernized foreign policy, an important step in making Japan a full member of the international community. The traditional East Asia worldview was based not on an international society of national units but on cultural distinctions and tributary relationships. Monks, scholars, and artists, rather than professional diplomatic envoys, had generally served as the conveyors of foreign policy. Foreign relations were related more to the sovereign's desires than to the public interest. For the next period of foreign relations, see History of Japanese foreign relations#1910–1941.

Foreign concessions in China were a group of concessions that existed during the late Imperial China and the Republic of China, which were governed and occupied by foreign powers, and are frequently associated with colonialism and imperialism.

The "century of humiliation" is a term used among the Sinosphere to describe the period in Chinese history beginning with the First Opium War (1839–1842), and ending in 1945 with China emerging out of the Second World War as one of the Big Four and established as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, or alternately, ending in 1949 with the founding of the People's Republic of China. The century-long period is typified by the decline, defeat and political fragmentation of the Qing dynasty and the subsequent Republic of China, which led to demoralizing foreign intervention, annexation and subjugation of China by Western powers, Russia, and Japan.

Yuxian (1842–1901) was a Manchu high official of the Qing dynasty who played an important role in the violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian Boxer Rebellion, which unfolded in northern China from the fall of 1899 to 1901. He was a local official who rose quickly from prefect of Caozhou to judicial commissioner and eventually governor of Shandong province. Dismissed from that post because of foreign pressure, he was soon named governor of Shanxi province. At the height of the Boxer crisis, as Allied armies invaded China in July 1900, he invited a group of 45 Christians and American missionaries to the provincial capital, Taiyuan, saying he would protect them from the Boxers. Instead, they were all killed. Foreigners, blaming Yuxian for what they called the Taiyuan Massacre, labeled him the "Butcher of Shan-hsi [Shanxi]".

Xu Jingcheng was a Chinese diplomat and Qing politician supportive of the Hundred Days' Reform. He was envoy to Belgium, France, Italy, Russia, Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany for the Qing imperial court and led reforms in modernizing China's railways and public works. As a modernizer and diplomat, he protested the breaches of international law in 1900 as one of the five ministers executed during the Boxer Rebellion. In Article IIa of the Boxer Protocol of 1901, the Eight-Nation Alliance that had provided military forces successfully pressed for the rehabilitation of Xu Jingcheng by an Imperial Edict of the Qing government:

Imperial Edict of the 13th February last rehabilitated the memories of Hsu Yung-yi, President of the Board of War; Li Shan, President of the Board of Works; Hsu Ching Cheng, Senior VicePresident of the Board of Civil Office; Lien Yuan, Vice-Chancellor of the Grand Council; and Yuan Chang, Vice-President of the Court of Sacrifices, who had been put to death for having protested against the outrageous breaches of international law of last year.

Events from the year 1875 in China.

The history of China–United States relations covers the relations of the United States with the Qing and Republic eras. For history after the 1949 founding of the People's Republic of China, see China–United States relations.