The Slavs or Slavic peoples are a group of peoples who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southeastern Europe, though there is a large Slavic minority scattered across the Baltic states, Northern Asia, and Central Asia, and a substantial Slavic diaspora in the Americas, Western Europe, and Northern Europe.

The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a set of revolutions that took place in the Austrian Empire from March 1848 to November 1849. Much of the revolutionary activity had a nationalist character: the Empire, ruled from Vienna, included ethnic Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs; all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

The Czech lands, then also known as Lands of the Bohemian Crown, were largely subject to the Habsburgs from the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 until the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. There were invasions by the Turks early in the period, and by the Prussians in the next century. The Habsburgs consolidated their rule and under Maria Theresa (1740–1780) adopted enlightened absolutism, with distinct institutions of the Bohemian Kingdom absorbed into centralized structures. After the Napoleonic Wars and the establishment of the Austrian Empire, a Czech National Revival began as a scholarly trend among educated Czechs, led by figures such as František Palacký. Czech nationalism took a more politically active form during the 1848 revolution, and began to come into conflict not only with the Habsburgs but with emerging German nationalism.

The Congress of Berlin was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at the meeting were Europe's then six great powers: Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Germany; the Ottomans; and four Balkan states: Greece, Serbia, Romania and Montenegro. The congress concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Berlin, replacing the preliminary Treaty of San Stefano that had been signed three months earlier.

The Yugoslav Committee was a World War I-era, unelected, ad-hoc committee that largely consisting of émigré Croat, Slovene, and Bosnian Serb politicians and political activists, whose aim was the detachment of Austro-Hungarian lands inhabited by South Slavs and unification of those lands with the Kingdom of Serbia. The group was formally established in 1915 and it last met in 1919, shortly after the breakup of Austria-Hungary and the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was later renamed Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Committee was led by it president the Croat lawyer Ante Trumbić and, until 1916, by Croat politician Frano Supilo as its vice president.

Anti-Slavic sentiment, also called Slavophobia, refers to prejudice, collective hatred, and discrimination directed at the various Slavic peoples. Accompanying racism and xenophobia, the most common manifestation of anti-Slavic sentiment throughout history has been the assertion that Slavs are inferior to other peoples. This sentiment peaked during World War II, when Nazi Germany classified Slavs— especially the Poles, Russians, Belarussians and Ukrainians—as "subhumans" and planned to exterminate a large number of them through the Generalplan Ost and Hunger Plan. Slavophobia also emerged twice in the United States: the first time was during the Progressive Era, when immigrants from Eastern Europe were met with opposition from the dominant class of Western European–origin American citizens; and again during the Cold War, when the United States became locked in an intensive global rivalry with the Soviet Union.

Austro-Slavism or Austrian Slavism was a political concept and program aimed to solve problems of Slavic peoples in the Austrian Empire. It was most influential among Czech liberals around the middle of the 19th century. First proposed by Karel Havlíček Borovský in 1846, as an opposition to the concept of pan-Slavism, it was further developed into a complete political program by Czech politician František Palacký. Austroslavism also found some support in other Slavic nations in the Austrian Empire, especially the Poles, Slovenes, Croats and Slovaks.

Greater Croatia is a term applied to certain currents within Croatian nationalism. In one sense, it refers to the territorial scope of the Croatian people, emphasising the ethnicity of those Croats living outside Croatia. In the political sense, though, the term refers to an irredentist belief in the equivalence between the territorial scope of the Croatian people and that of the Croatian state.

The Czech Corridor or Czechoslovak Corridor was a failed proposal during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 in the aftermath of World War I and the breakup of Austria-Hungary. The proposal would have carved out a strip of land between Austria and Hungary to serve as a corridor between two newly formed Slavic countries with shared interests, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia) and Czechoslovakia. A different name often given is Czech–Yugoslav Territorial Corridor. It is primarily referred to as "the Czech Corridor" today, because representatives of Yugoslavia at the Peace Conference stated that they would prefer it if the corridor were to be controlled solely by Czechoslovaks. The proposal was ultimately rejected by the conference and never again suggested.

The Serb-Catholic movement in Dubrovnik was a cultural and political movement of people from Dubrovnik who, while Catholic, declared themselves Serbs, while Dubrovnik was part of the Habsburg-ruled Kingdom of Dalmatia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially spearheaded by intellectuals who espoused strong pro-Serbian sentiments, there were two prominent incarnations of the movement: an early pan-Slavic phase under Matija Ban and Medo Pucić that corresponded to the Illyrian movement, and a later, more Serbian nationalist group that was active between the 1880s and 1908, including a large number of Dubrovnik intellectuals at the time. The movement, whose adherents are known as Serb-Catholics or Catholic Serbs, largely disappeared with the creation of Yugoslavia.

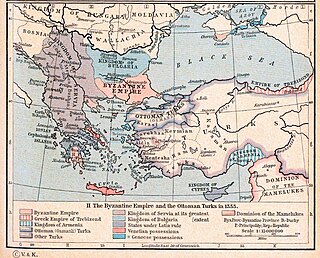

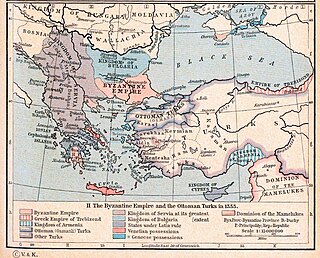

Serbian nationalism asserts that Serbs are a nation and promotes the cultural and political unity of Serbs. It is an ethnic nationalism, originally arising in the context of the general rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule, under the influence of Serbian linguist Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and Serbian statesman Ilija Garašanin. Serbian nationalism was an important factor during the Balkan Wars which contributed to the decline of the Ottoman Empire, during and after World War I when it contributed to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and again during the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s.

Yugoslavia was a state concept among the South Slavic intelligentsia and later popular masses from the 19th to early 20th centuries that culminated in its realization after the 1918 collapse of Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I and the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. However, the kingdom was better known colloquially as Yugoslavia ; in 1929 it was formally renamed the "Kingdom of Yugoslavia".

The Croat-Serb Coalition was a major political alliance in Austria-Hungary during early 20th century that governed the Croatian lands, the crownlands of Croatia-Slavonia and Dalmatia. It represented the political idea of a cooperation of Croats and Serbs in Austria-Hungary for mutual benefit. Its main leaders were, at first Frano Supilo and Svetozar Pribićević, then Pribićević alone.

Yugoslavism, Yugoslavdom, or Yugoslav nationalism is an ideology supporting the notion that the South Slavs, namely the Bosniaks, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes, but also Bulgarians, belong to a single Yugoslav nation separated by diverging historical circumstances, forms of speech, and religious divides. During the interwar period, Yugoslavism became predominant in, and then the official ideology of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. There were two major forms of Yugoslavism in the period: the regime favoured integral Yugoslavism promoting unitarism, centralisation, and unification of the country's ethnic groups into a single Yugoslav nation, by coercion if necessary. The approach was also applied to languages spoken in the Kingdom. The main alternative was federalist Yugoslavism which advocated the autonomy of the historical lands in the form of a federation and gradual unification without outside pressure. Both agreed on the concept of National Oneness developed as an expression of the strategic alliance of South Slavs in Austria-Hungary in the early 20th century. The concept was meant as a notion that the South Slavs belong to a single "race", were of "one blood", and had shared language. It was considered neutral regarding the choice of centralism or federalism.

History of modern Serbia or modern history of Serbia covers the history of Serbia since national awakening in the early 19th century from the Ottoman Empire, then Yugoslavia, to the present day Republic of Serbia. The era follows the early modern history of Serbia.

The May Declaration was a manifesto of political demands for unification of South Slav-inhabited territories within Austria-Hungary put forward to the Imperial Council in Vienna on 30 May 1917. It was authored by Anton Korošec, the leader of the Slovene People's Party. The document was signed by Korošec and thirty-two other council delegates representing South-Slavic lands within the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy – the Slovene Lands, the Dalmatia, Istria, and the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The delegates who signed the declaration were known as the Yugoslav Club.

The National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was a group of political representatives of South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary and subsequently in the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs formed in the wake of dissolution of Austria-Hungary. It was established in Zagreb on 8 October 1918, largely composed of members of various representative bodies operating in Habsburg crown lands inhabited by South Slavs. Founding of the National Council was fulfilment of the Zagreb Resolution on concentration of South Slavic political forces adopted earlier that year on the initiative of the Yugoslav Club. The council elected its central committee and the presidency led by Anton Korošec as the president and by Svetozar Pribičević and Ante Pavelić as vice-presidents.

Neo-Slavism was a short-lived movement originating in Austria-Hungary around 1908 and influencing nearby Slavic states in the Balkans as well as Russia. Neo-Slavists promoted cooperation between Slavs on equal terms in order to resist Germanization, pursue modernization and liberal reforms, and wanted to create a democratic community of Slavic nations without the dominating influence of Russia.

In the history of Austria-Hungary, trialism was the political movement that aimed to reorganize the bipartite Empire into a tripartite one, creating a Croatian state equal in status to Austria and Hungary. Franz Ferdinand promoted trialism before his assassination in 1914 to prevent the Empire from being ripped apart by Slavic dissent. The Empire would be restructured three ways instead of two, with the Slavic element given representation at the highest levels equivalent to what Austria and Hungary had at the time. Serbians saw this as a threat to their dream of a new state of Yugoslavia. Hungarian leaders had a predominant voice in imperial circles and strongly rejected Trialism because it would liberate many of their minorities from Hungarian rule they considered oppressive.

The First Serbian Volunteer Division or First Serbian Division, was a military formation of the First World War, created by Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, and organised in the city of Odessa in early 1916. This independent volunteer unit was primarily made up of South Slav Habsburg prisoners of war, detained in Russia, who had requested to fight alongside the Serbian Army. It also included men from South Slav diaspora communities, especially the United States.