The Drago Doctrine was announced in 1902 by Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs Luis María Drago in a diplomatic note to the United States. This doctrine stated that simply failing to repay national debt was not a valid reason for foreign intervention, especially by a power outside of the Western Hemisphere. The doctrine was a response to the European powers' blockade of Venezuela, which occurred after the country defaulted on its debt. Washington accepted and used the Drago doctrine. In order to prevent further interventions, the United States took control of the customs of several Latin American countries to ensure debt payments were made to Europe.

Big stick ideology, big stick diplomacy, big stick philosophy, or big stick policy refers to an aphorism often said by the 26th president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt; "speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far". The American press during his time, as well as many modern historians today, used the term "big stick" to describe the foreign policy positions during his administration. Roosevelt described his style of foreign policy as "the exercise of intelligent forethought and of decisive action sufficiently far in advance of any likely crisis". As practiced by Roosevelt, big stick diplomacy had five components. First, it was essential to possess serious military capability that would force the adversary to pay close attention. At the time that meant a world-class navy; Roosevelt never had a large army at his disposal. The other qualities were to act justly toward other nations, never to bluff, to strike only when prepared to strike hard, and to be willing to allow the adversary to save face in defeat.

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. The corollary states that the United States could intervene in the internal affairs of Latin American countries if they committed flagrant wrongdoings that "loosened the ties of civilized society".

The Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, President Woodrow Wilson had previously used the term, but subsequently went on to justify U.S. involvement in the Mexican Revolution and occupation of Haiti. Senator Henry Clay had coined the term Good Neighbor in the previous century. President Herbert Hoover turned against interventionism and developed policies that Roosevelt perfected.

A United States presidential doctrine comprises the key goals, attitudes, or stances for United States foreign affairs outlined by a president. Most presidential doctrines are related to the Cold War. Though many U.S. presidents had themes related to their handling of foreign policy, the term doctrine generally applies to presidents such as James Monroe, Harry S. Truman, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, all of whom had doctrines which more completely characterized their foreign policy.

The Clark Memorandum on the Monroe Doctrine or Clark Memorandum, written on December 17, 1928 by Calvin Coolidge's undersecretary of state J. Reuben Clark, concerned the United States' use of military force to intervene in Latin American nations. This memorandum was a secret until it was officially released in 1930 by the Herbert Hoover administration.

The Havana Conference was a conference held in the Cuban capital, Havana, from July 21 to July 30, 1940. At the meeting by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the United States, Panama, Mexico, Ecuador, Cuba, Costa Rica, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Honduras, Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Bolivia, Haiti and El Salvador agreed to collectively govern territories of nations that were taken over by the Axis powers of World War II and also declared that an attack on any nation in the region would be considered as an attack on all nations.

The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance is an agreement signed in 1947 in Rio de Janeiro among many countries of the Americas. The central principle contained in its articles is that an attack against one is to be considered an attack against them all; this was known as the "hemispheric defense" doctrine. Despite this, several members have breached the treaty on multiple occasions. The treaty was initially created in 1947 and came into force in 1948, in accordance with Article 22 of the treaty. The Bahamas was the most recent country to sign and ratify it in 1982.

The Johnson Doctrine, enunciated by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson after the United States' intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965, declared that domestic revolution in the Western Hemisphere would no longer be a local matter when the object is the establishment of a "Communist dictatorship". During Johnson's presidency, the United States again began interfering in the affairs of sovereign nations, particularly Latin America. The Johnson Doctrine is the formal declaration of the intention of the United States to intervene in such affairs. It is an extension of the Eisenhower and Kennedy Doctrines.

The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, later known as the Office for Inter-American Affairs, was a United States agency promoting inter-American cooperation (Pan-Americanism) during the 1940s, especially in commercial and economic areas. It was started in August 1940 as OCCCRBAR with Nelson Rockefeller as its head, appointed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The Conferences of American States, commonly referred to as the Pan-American Conferences, were meetings of the Pan-American Union, an international organization for cooperation on trade. James G. Blaine, a United States politician, Secretary of State and presidential contender, first proposed establishment of closer ties between the United States and its southern neighbors and proposed international conference. Blaine hoped that ties between the United States and its southern counterparts would open Latin American markets to US trade.

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934. The military interventions were primarily carried out by the United States Marine Corps, which also developed a manual, the Small Wars Manual (1921) based on their experiences. On occasion, the United States Navy provided gunfire support and the United States Army also deployed troops.

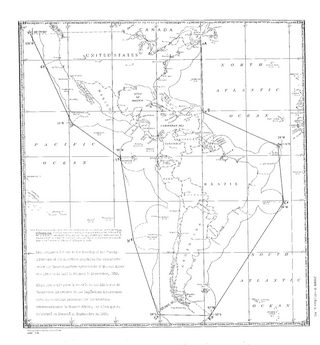

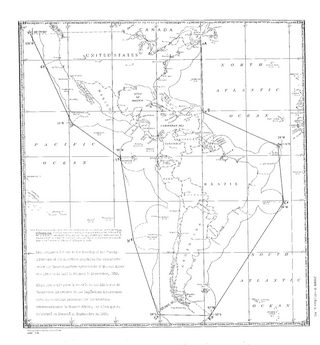

The Monroe Doctrine is a United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers is a potentially hostile act against the United States. The doctrine was central to American grand strategy in the 20th century.

Viva América was an American musical radio program which was broadcast live over the CBS radio network and to North and South America over the "La Cadena de las Américas" during the 1940s (1942–1949) in support of Pan-Americanism during World War II. It was also broadcast for the benefit of members of the armed forces in Europe during World War II over the Armed Forces Network. All broadcasts of this program were supervised under the strict government supervision of the United States Department of State and the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) as part of the United States Cultural Exchange Programs cultural diplomacy initiative authorized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II through the Office for Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations (OCCCRBAR) and the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs directed by Nelson Rockefeller.

Edmund Albert Chester Sr. was an American television executive. He served as a vice president and executive at the CBS radio and television networks during the 1940s. As Director of Latin American Relations he collaborated with the Department of State to develop CBS's "La Cadena de Las Americas" radio network in support of Pan-Americanism during World War II. He also served as a highly respected journalist and Bureau Chief for Latin America at Associated Press and Vice President at La Prensa Asociada in the 1930s. He was awarded the Carlos Manuel de Cespedes National Order of Merit by the government of Cuba in recognition of his efforts to foster greater understanding between the peoples of Cuba and the United States of America.

Historically speaking, bilateral relations between the various countries of Latin America and the United States of America have been multifaceted and complex, at times defined by strong regional cooperation and at others filled with economic and political tension and rivalry. Although relations between the U.S. government and most of Latin America were limited prior to the late 1800s, for most of the past century, the United States has unofficially regarded parts of Latin America as within its sphere of influence, and for much of the Cold War (1947–1991), actively vied with the Soviet Union for influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Francisco García Calderón Rey was a Peruvian writer. He was son of Francisco García Calderón.

The Panama Conference was a meeting by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the United States, Panama, Mexico, Ecuador, Cuba, Costa Rica, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Honduras, Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Bolivia, Haiti and El Salvador in Panama City at the Republic of Panama on September 23, 1939, shortly after the beginning of World War II in Europe.

The Inter-American Commission of Women, abbreviated CIM, is an organization that falls within the Organization of American States. It was established in 1928 by the Sixth Pan-American Conference and is composed of one female representative from each Republic in the Union. In 1938, the CIM was made a permanent organization, with the goal of studying and addressing women's issues in the Americas.

The foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration covers American foreign policy from 1901 to 1909, with attention to the main diplomatic and military issues, as well as topics such as immigration restriction and trade policy. For the administration as a whole see Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America where he began construction of the Panama Canal. He modernized the U.S. Army and expanded the Navy. He sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project American naval power. Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of U.S. influence begun under President William McKinley (1897–1901). Roosevelt presided over a rapprochement with the Great Britain. He promulgated the Roosevelt Corollary, which held that the United States would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries in order to forestall direct European intervention. Partly as a result of the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States would engage in a series of interventions in Latin America, known as the Banana Wars. After Colombia rejected a treaty granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama, Roosevelt supported the secession of Panama. He subsequently signed a treaty with Panama which established the Panama Canal Zone. The Panama Canal was completed in 1914, greatly reducing transport time between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Roosevelt's well-publicized actions were widely applauded.