Bosnia and Herzegovina, is a country in Southeast Europe on the Balkan Peninsula. It has had permanent settlement since the Neolithic Age. By the early historical period it was inhabited by Illyrians and Celts. Christianity arrived in the 1st century, and by the 4th century the area became part of the Western Roman Empire. Germanic tribes invaded soon after, followed by Slavs in the 6th century.

The Balkans and parts of this area are alternatively situated in Southeastern, Southern, Eastern Europe and Central Europe. The distinct identity and fragmentation of the Balkans owes much to its common and often turbulent history regarding centuries of Ottoman conquest and to its very mountainous geography.

Croatian nationalism is nationalism that asserts the nationality of Croats and promotes the cultural unity of Croats.

Mate Boban was a Bosnian Croat politician and one of the founders of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, an unrecognized entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was the 1st President of Herzeg-Bosnia from 1991 until 1994.

Blaž Nikola Kraljević was a Bosnian Croat paramilitary leader who commanded the Croatian Defence Forces (HOS) during the Bosnian War. An immigrant to Australia, Kraljević joined the Croatian Revolutionary Brotherhood (HRB) upon his arrival there in 1967. During his return to Yugoslavia in January 1992 he was appointed by Dobroslav Paraga, leader of the Croatian Party of Rights (HSP), as leader of the HOS in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia was an unrecognized geopolitical entity and quasi-state in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was proclaimed on 18 November 1991 under the name Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia as a "political, cultural, economic and territorial whole" in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and abolished on 14 August 1996.

Bosniaks are a mainly-muslim South Slavic ethnic group, native to the region of Bosnia and the region of Sandžak. The term Bosniaks was re-instated in 1993 after decades of suppression in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Bosniak Assembly adopted the ethnonym to replace "Bosnian Muslims." Scholars believe that the move was partly motivated by a desire to distinguish the Bosniaks from the fabricated and imposed term Muslim to describe their nationality in the former Yugoslavia. These scholars contend that the Bosniaks are distinguishable from comparable groups due to a collective identity based on a shared environment, cultural practices and experiences.

The Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina, often referred to as Bosnian Croats or Herzegovinian Croats, are native and the third most populous ethnic group in Bosnia and Herzegovina, after Bosniaks and Serbs, and are one of the constitutive nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina have made significant contributions to the culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Most Croats declare themselves Catholics and speakers of the Croatian language.

The Croat–Bosniak War was a conflict between the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, supported by Croatia, that lasted from 18 October 1992 to 23 February 1994. It is often referred to as a "war within a war" because it was part of the larger Bosnian War. In the beginning, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) fought together in an alliance against the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS). By the end of 1992, however, tensions between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats increased. The first armed incidents between them occurred in October 1992 in central Bosnia. The military alliance continued until early 1993, when it mostly fell apart and the two former allies engaged in open conflict.

The Graz agreement was a proposed agreement made between the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić and the Bosnian Croat leader Mate Boban on 6 May 1992 in the city of Graz, Austria. The agreement publicly declared the territorial division between Republika Srpska and the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia and called for an end of conflicts between Serbs and Croats. The largest group in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bosniaks, did not take part in the agreement and were purposefully not invited to the negotiations.

Bosniak nationalism or Bosniakdom is the nationalism that asserts the nationality of Bosniaks and promotes the cultural unity of the Bosniaks. It should not be confused with Bosnian nationalism, often referred to as Bosniandom, as Bosniaks are treated as a constituent people by the preamble of Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, whereas people who identify as Bosnians for nationality are not. Bosniaks were formerly called Muslims in census data but this model was last used in the 1991 census.

The Bosniaks are a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia, which is today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who share a common Bosnian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Kosovo as well as in Austria, Germany, Turkey and Sweden. They also constitute a significant diaspora with several communities across Europe, the Americas and Oceania.

The Croat–Bosniak War was a conflict between the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia, supported by Croatia, that lasted from 19 June 1992 – 23 February 1994. The Croat-Bosniak War is often referred to as a "war within a war" because it was part of the larger Bosnian War.

Yugoslavism, Yugoslavdom, or Yugoslav nationalism is an ideology supporting the notion that the South Slavs, namely the Bosniaks, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes, but also Bulgarians, belong to a single Yugoslav nation separated by diverging historical circumstances, forms of speech, and religious divides. During the interwar period, Yugoslavism became predominant in, and then the official ideology of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. There were two major forms of Yugoslavism in the period: the regime favoured integral Yugoslavism promoting unitarism, centralisation, and unification of the country's ethnic groups into a single Yugoslav nation, by coercion if necessary. The approach was also applied to languages spoken in the Kingdom. The main alternative was federalist Yugoslavism which advocated the autonomy of the historical lands in the form of a federation and gradual unification without outside pressure. Both agreed on the concept of National Oneness developed as an expression of the strategic alliance of South Slavs in Austria-Hungary in the early 20th century. The concept was meant as a notion that the South Slavs belong to a single "race", were of "one blood", and had shared language. It was considered neutral regarding the choice of centralism or federalism.

The May Declaration was a manifesto of political demands for unification of South Slav-inhabited territories within Austria-Hungary put forward to the Imperial Council in Vienna on 30 May 1917. It was authored by Anton Korošec, the leader of the Slovene People's Party. The document was signed by Korošec and thirty-two other council delegates representing South-Slavic lands within the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy – the Slovene Lands, the Dalmatia, Istria, and the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The delegates who signed the declaration were known as the Yugoslav Club.

The siege of Mostar was fought during the Bosnian War first in 1992 and then again later in 1993 to 1994. Initially lasting between April 1992 and June 1992, it involved the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) and the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) fighting against the Serb-dominated Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) after Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia. That phase ended in June 1992 after the success of Operation Jackal, launched by the Croatian Army (HV) and HVO. As a result of the first siege around 90,000 residents of Mostar fled and numerous religious buildings, cultural institutions, and bridges were damaged or destroyed.

Turkish Croatia was a geopolitical term which appeared periodically during the Ottoman–Habsburg wars between the late 16th to late 18th century. Invented by Austrian military cartographers, it referred to a border area of Bosnia located across the Ottoman-Austrian border from the Croatian Military Frontier. It went out of use with the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia was signed by Alija Izetbegović, President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Franjo Tuđman, President of the Republic of Croatia, in Zagreb on 21 July 1992 during the Bosnian and Croatian wars for independence from Yugoslavia. It established cooperation, albeit inharmonious, between the two and served as a basis for joint defense against Serb forces. It also placed the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) under the command of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH).

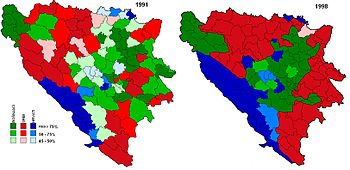

The partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina was discussed and attempted during the 20th century. The issue came to prominence during the Bosnian War, which also involved Bosnia and Herzegovina's largest neighbors, Croatia and Serbia. As of 2023, the country remains one state while internal political divisions of Bosnia and Herzegovina based on the 1995 Dayton Agreement remain in place.

Anti-Croat sentiment or Croatophobia is discrimination or prejudice against Croats as an ethnic group and it also consists of negative feelings towards Croatia as a country.