Related Research Articles

Chicano or Chicana is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who have a non-Anglo self-image, embracing their Mexican Native ancestry. Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent. Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into the mainstream American culture and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance. The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.

Mexican Americans are Americans of Mexican heritage. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United States; they make up 53% of the total population of foreign-born Hispanic Americans and 25% of the total foreign-born population. Chicano is a term used by some to describe the unique identity held by Mexican-Americans. The United States is home to the second-largest Mexican community in the world, behind only Mexico. Most Mexican Americans reside in the Southwest, with over 60% of Mexican Americans living in the states of California and Texas.

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greater autonomy are usually not considered separatists. Some discourse settings equate separatism with religious segregation, racial segregation, or sex segregation, while other discourse settings take the broader view that separation by choice may serve useful purposes and is not the same as government-enforced segregation. There is some academic debate about this definition, and in particular how it relates to secessionism, as has been discussed online.

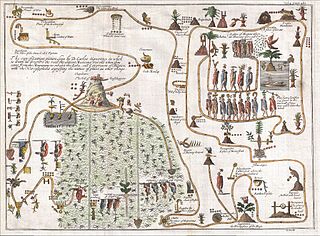

“Aztlán” is the legendary ancestral home of the Aztec peoples. The word Aztecah is the Nahuatl word for "people from Aztlán", from which was derived the word Aztec. Aztlán is mentioned in several ethnohistorical sources dating from the colonial period, and while they each cite varying lists of the different tribal groups who participated in the migration from Aztlán to central Mexico, the Mexica who later founded Mexico-Tenochtitlan are mentioned in all of the accounts.

The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was a pro-indigenist manifesto advocating Chicano nationalism and self-determination for Mexican Americans. It was adopted by the First National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference, a March 1969 convention hosted by Rodolfo Gonzales's Crusade for Justice in Denver, Colorado.

The Reconquista ("reconquest") is a term to describe an irredentist vision by different individuals, groups, and/or nations that the Southwestern United States should be politically or culturally returned to Mexico. Known as advocating a Greater Mexico, such opinions are often formed on the basis that those territories were claimed by Spain for centuries and then by Mexico from 1821 until they were annexed by the United States during the Texas Annexation (1845) and the Mexican Cession (1848) because of the Mexican–American War.

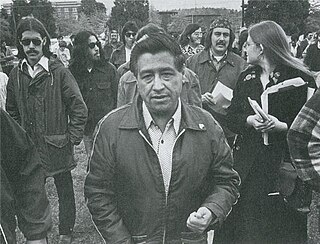

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was a Mexican-American boxer, poet, political organizer, and activist. He was one of many leaders for the Crusade for Justice in Denver, Colorado. The Crusade for Justice was an urban rights and Chicano cultural urban movement during the 1960s focusing on social, political, and economic justice for Chicanos. Gonzales convened the first-ever Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in 1968, which was poorly attended due to timing and weather conditions. He tried again in March 1969, and established what is commonly known as the First Chicano Youth Liberation Conference. This conference was attended by many future Chicano activists and artists. It also birthed the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, a pro-indigenist manifesto advocating revolutionary Chicano nationalism and self-determination for all Chicanos. Through the Crusade for Justice, Gonzales organized the Mexican American people of Denver to fight for their cultural, political, and economic rights, leaving his mark on history. He was honored with a Google Doodle in continued celebration of National Hispanic Heritage Month in the United States on 30 September 2021.

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation. Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.

In Hispanic America, criollo is a term used originally to describe people of full Spanish descent born in the viceroyalties. In different Latin American countries, the word has come to have different meanings, mostly referring to the local-born majority.

Chicano studies, also known as Chicano/a studies, Chican@ studies, or Xicano studies originates from the Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, and is the study of the Chicano and Latino experience. Chicano studies draws upon a variety of fields, including history, sociology, the arts, and Chicano literature. The area of studies additionally emphasizes the importance of Chicano educational materials taught by Chicano educators for Chicano students.

I Am Joaquin, by Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales and translated by Juanita Dominguez, is a famous epic poem associated with the Chicano movement of the 1960s in the United States. In I am Joaquin, Joaquin speaks of the struggles that the Chicano people have faced in trying to achieve economic justice and equal rights in the U.S., as well as to find an identity of being part of a hybrid mestizo society. He promises that his culture will survive if all Chicano people stand proud and demand acceptance.

Las Adelitas de Aztlán was a short-lived Mexican American female civil rights organization that was created by Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes in 1970. Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes were all former members of the Brown Berets, another Mexican American Civil rights organization that had operated concurrently during the 1960s and 1970s in the California area. The founders left the Brown Berets due to enlarging gender discrepancies and disagreements that caused much alienation amongst their female members. The Las Adelitas De Aztlan advocated for Mexican-American Civil rights, better conditions for workers, protested police brutality and advocated for women's rights for the Latino community. The name of the organization was a tribute to Mexican female soldiers or soldaderas that fought during the Mexican Revolution of the early twentieth century.

Mexican American literature is literature written by Mexican Americans in the United States. Although its origins can be traced back to the sixteenth century, the bulk of Mexican American literature dates from post-1848 and the United States annexation of large parts of Mexico in the wake of the Mexican–American War. Today, as a part of American literature in general, this genre includes a vibrant and diverse set of narratives, prompting critics to describe it as providing "a new awareness of the historical and cultural independence of both northern and southern American hemispheres". Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican American literature.

Miguel Méndez was the pen name for Miguel Méndez Morales, a Mexican American author best known for his novel Peregrinos de Aztlán. He was a leading figure in the field of Chicano literature.

Chicana literature is a form of literature that has emerged from the Chicana Feminist movement. It aims to redefine Chicana archetypes in an effort to provide positive models for Chicanas. Chicana writers redefine their relationships with what Gloria Anzaldúa has called "Las Tres Madres" of Mexican culture by depicting them as feminist sources of strength and compassion.

The Chicano Art Movement represents groundbreaking movements by Mexican-American artists to establish a unique artistic identity in the United States. Much of the art and the artists creating Chicano Art were heavily influenced by Chicano Movement which began in the 1960s.

This is a Mexican American bibliography. This list consists of books, and journal articles, about Mexican Americans, Chicanos, and their history and culture. The list includes works of literature whose subject matter is significantly about Mexican Americans and the Chicano/a experience. This list does not include works by Mexican American writers which do not address the topic, such as science texts by Mexican American writers.

Mexican-American folklore refers to the tales and history of Chicano people who live in the United States.

The term Chicanafuturism was originated by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez which she introduced in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies in 2004. The term is a portmanteau of 'chicana' and 'futurism', inspired by the developing movement of Afrofuturism. The word 'chicana' refers to a woman or girl of Mexican origin or descent. However, 'Chicana' itself serves as a chosen identity for many female Mexican Americans in the United States, to express self-determination and solidarity in a shared cultural, ethnic, and communal identity while openly rejecting assimilation. Ramírez created the concept of Chicanafuturism as a response to white androcentrism that she felt permeated science-fiction and American society. Chicanafuturism can be understood as part of a larger genre of Latino futurisms.

Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican-American literature that emerged from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano literature formed out of the political and cultural struggle of Chicana/os to develop a political foundation and identity that rejected Anglo-American hegemony. This literature embraced the pre-Columbian roots of Mexican-Americans, especially those who identify as Chicana/os.

References

- Chávez, Ernesto. "Mi raza primero!" (My people first!): nationalism, identity, and insurgency in the Chicano movement in Los Angeles, 1966–1978 Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0-520-23018-3.