The Battle of Verdun was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north of Verdun-sur-Meuse. The German 5th Army attacked the defences of the Fortified Region of Verdun and those of the French Second Army on the right (east) bank of the Meuse. Using the experience of the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, the Germans planned to capture the Meuse Heights, an excellent defensive position, with good observation for artillery-fire on Verdun. The Germans hoped that the French would commit their strategic reserve to recapture the position and suffer catastrophic losses at little cost to the German infantry.

The Battle of the Somme, also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 November 1916 on both sides of the upper reaches of the river Somme in France. The battle was intended to hasten a victory for the Allies. More than three million men fought in the battle, of whom one million were either wounded or killed, making it one of the deadliest battles in all of human history.

The Battle of Loos took place from 25 September to 8 October 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. The French and British tried to break through the German defences in Artois and Champagne and restore a war of movement. Despite improved methods, more ammunition and better equipment, the Franco-British attacks were largely contained by the Germans, except for local losses of ground. The British gas attack failed to neutralize the defenders and the artillery bombardment was too short to destroy the barbed wire or machine gun nests. German tactical defensive proficiency was still dramatically superior to the British offensive planning and doctrine, resulting in a British defeat.

The First Battle of Ypres was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German, French, Belgian armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fought from Arras in France to Nieuwpoort (Nieuport) on the Belgian coast, from 10 October to mid-November. The battles at Ypres began at the end of the Race to the Sea, reciprocal attempts by the German and Franco-British armies to advance past the northern flank of their opponents. North of Ypres, the fighting continued in the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October), between the German 4th Army, the Belgian army and French marines.

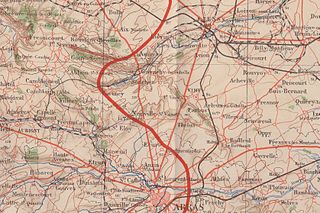

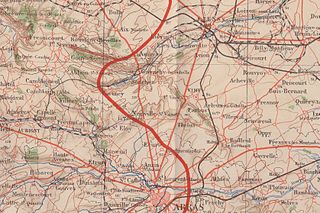

The Hindenburg Line was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 1916, the Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme left the German western armies exhausted and on the Eastern Front, the Brusilov Offensive had inflicted huge losses on the Austro-Hungarian armies and forced the Germans to take over more of the front. The declaration of war by Romania had placed additional strain on the German army and war economy.

The Race to the Sea took place from about 17 September – 19 October 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers and the German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September) and was followed by the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September), a Franco-British counter-offensive. The term describes reciprocal attempts by the Franco-British and German armies to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army through the provinces of Picardy, Artois and Flanders, rather than an attempt to advance northwards to the sea. The "race" ended on the North Sea coast of Belgium around 19 October, when the last open area from Diksmuide to the North Sea was occupied by Belgian troops who had retreated after the Siege of Antwerp. The outflanking attempts had resulted in a number of encounter battles but neither side was able to gain a decisive victory.

The Battle of the Frontiers comprised battles fought along the eastern frontier of France and in southern Belgium, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. The battles resolved the military strategies of the French Chief of Staff General Joseph Joffre with Plan XVII and an offensive adaptation of the German Aufmarsch II deployment plan by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. The German concentration on the right (northern) flank, was to wheel through Belgium and attack the French in the rear.

The Second Battle of Artois from 9 May to 18 June 1915, took place on the Western Front during the First World War. A German-held salient from Reims to Amiens had been formed in 1914 which menaced communications between Paris and the unoccupied parts of northern France. A reciprocal French advance eastwards in Artois could cut the rail lines supplying the German armies between Arras and Reims. French operations in Artois, Champagne and Alsace from November–December 1914, led General Joseph Joffre, Generalissimo and head of Grand Quartier Général (GQG), to continue the offensive in Champagne against the German southern rail supply route and to plan an offensive in Artois against the lines from Germany supplying the German armies in the north.

The Third Battle of Artois was fought by the French Tenth Army against the German 6th Army on the Western Front of the First World War. The battle included the Battle of Loos by the British First Army. The offensive, meant to complement the Second Battle of Champagne, was the last attempt that year by Joseph Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, to exploit an Allied numerical advantage over Germany. Simultaneous attacks were planned in Champagne-Ardenne to capture the railway at Attigny and in Artois to take the railway line through Douai, to force a German withdrawal from the Noyon salient.

The Great Retreat, also known as the retreat from Mons, was the long withdrawal to the River Marne in August and September 1914 by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army. The Franco-British forces on the Western Front in the First World War had been defeated by the armies of the German Empire at the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. A counter-offensive by the Fifth Army, with some assistance from the BEF, at the First Battle of Guise failed to end the German advance and the retreat continued over the Marne. From 5 to 12 September, the First Battle of the Marne ended the Allied retreat and forced the German armies to retire towards the Aisne River and to fight the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September). Reciprocal attempts to outflank the opposing armies to the north known as the Race to the Sea followed from (17 September to 17 October).

The Second Battle of the Aisne was the main part of the Nivelle Offensive, a Franco-British attempt to inflict a decisive defeat on the German armies in France. The Entente strategy was to conduct offensives from north to south, beginning with an attack by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) then the main attack by two French army groups on the Aisne. General Robert Nivelle planned the offensive in December 1916, after he replaced Joseph Joffre as Commander-in-Chief of the French Army.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge and possibly Lille. A French assault at Vimy Ridge on the Artois plateau was also planned to threaten the road, rail and canal junctions at La Bassée from the south as the British attacked from the north. The British attackers broke through German defences in a salient at the village of Neuve-Chapelle but the success could not be exploited.

Winter operations 1914–1915 is the name given to military operations during the First World War, from 23 November 1914 – 6 February 1915, in the 1921 report of the British government Battles Nomenclature Committee. The operations took place on the part of the Western Front held by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), in French and Belgian Flanders.

The actions of the Hohenzollern Redoubt took place on the Western Front in World War I from 13 to 19 October 1915, at the Hohenzollern Redoubt near Auchy-les-Mines in France. In the aftermath of the Battle of Loos, the 9th (Scottish) Division captured the strongpoint and then lost it to a German counter-attack. The British attack on 13 October failed and resulted in 3,643 casualties, mostly in the first few minutes. In the History of the Great War, James Edmonds wrote that "The fighting [from 13 to 14 October] had not improved the general situation in any way and had brought nothing but useless slaughter of infantry".

The Battle of Aubers was a British offensive on the Western Front on 9 May 1915 during the First World War. The battle was part of the British contribution to the Second Battle of Artois, a Franco-British offensive intended to exploit the German diversion of troops to the Eastern Front. The French Tenth Army was to attack the German 6th Army north of Arras and capture Vimy Ridge, preparatory to an advance on Cambrai and Douai. The British First Army, on the left (northern) flank of the Tenth Army, was to attack on the same day and widen the gap in the German defences expected to be made by the Tenth Army and to fix German troops north of La Bassée Canal.

The Battle of Arras, was an attempt by the French Army to outflank the German Army, which was attempting to do the same thing during the "Race to the Sea", the reciprocal attempts by both sides, to exploit conditions created during the First Battle of the Aisne. At the First Battle of Picardy (22–26 September) each side had attacked expecting to advance round an open northern flank and found instead that troops had arrived from further south and extended the flank northwards.

The First Battle of Champagne was fought from 20 December 1914 – 17 March 1915 in World War I in the Champagne region of France and was the second offensive by the Allies against the German Empire since mobile warfare had ended after the First Battle of Ypres in Flanders (19 October – 22 November 1914). The battle was fought by the French Fourth Army and the German 3rd Army. The offensive was part of a French strategy to attack the Noyon Salient, a large bulge in the new Western Front, which ran from Switzerland to the North Sea. The First Battle of Artois began on the northern flank of the salient on 17 December and the offensive against the southern flank in Champagne began three days later.

The Battle of Grand Couronné from 4 to 13 September 1914, took place in France after the Battle of the Frontiers, at the beginning of the First World War. After the German victories of Sarrebourg and Morhange, pursuit by the German 6th Army and the 7th Army, took four days to regain contact with the French and attack to break through French defences on the Moselle.

The Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf was a series of engagements during the First World War fought for the control of the Hartmannswillerkopf peak in Alsace in 1914 and 1915. The peak is a pyramidal rocky spur in the Vosges mountains, about 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Thann, standing at 956 m (3,136 ft) and overlooking the Alsace Plain, Rhine valley and the Black Forest in Germany. Hartmanswillerkopf was captured by the French army during the Battle of Mulhouse (7–10, 14–26 August 1914). From the vantage point, Mulhouse and the Mulhouse–Colmar railway could be seen and the French railway from Thann to Cernay and Belfort shielded from German observation.

The Battle of Hébuterne, took place from 7 to 13 June 1915 on the Western Front in Picardy, during the First World War. The French Second Army conducted the attack as part of a general action by several French armies, to hinder the movement of German reserves to Vimy Ridge, during the decisive action of the Tenth Army in the Second Battle of Artois.