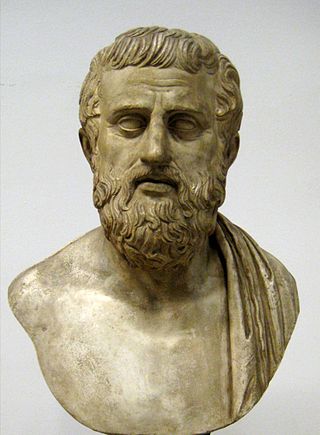

Aeschylus was an ancient Greek tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is largely based on inferences made from reading his surviving plays. According to Aristotle, he expanded the number of characters in the theatre and allowed conflict among them. Formerly, characters interacted only with the chorus.

Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him, but the Suda says it was ninety-two at most. Of these, eighteen or nineteen have survived more or less complete. There are many fragments of most of his other plays. More of his plays have survived intact than those of Aeschylus and Sophocles together, partly because his popularity grew as theirs declined—he became, in the Hellenistic Age, a cornerstone of ancient literary education, along with Homer, Demosthenes, and Menander.

Sophocles was an ancient Greek tragedian, known as one of three from whom at least one play has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those of Aeschylus; and earlier than, or contemporary with, those of Euripides. Sophocles wrote over 120 plays, but only seven have survived in a complete form: Ajax, Antigone, Women of Trachis, Oedipus Rex, Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus. For almost fifty years, Sophocles was the most celebrated playwright in the dramatic competitions of the city-state of Athens which took place during the religious festivals of the Lenaea and the Dionysia. He competed in thirty competitions, won twenty-four, and was never judged lower than second place. Aeschylus won thirteen competitions, and was sometimes defeated by Sophocles; Euripides won four.

Tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsis, or a "pain [that] awakens pleasure,” for the audience. While many cultures have developed forms that provoke this paradoxical response, the term tragedy often refers to a specific tradition of drama that has played a unique and important role historically in the self-definition of Western civilization. That tradition has been multiple and discontinuous, yet the term has often been used to invoke a powerful effect of cultural identity and historical continuity—"the Greeks and the Elizabethans, in one cultural form; Hellenes and Christians, in a common activity," as Raymond Williams puts it.

In Greek mythology, Pleisthenes or Plisthenes, is the name of several members of the house of Tantalus, the most important being a son of Atreus, said to be the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. Although these two brothers are usually considered to be the sons of Atreus himself, according to some accounts, Pleisthenes was their father, but he died, and Agamemnon and Menelaus were adopted by their grandfather Atreus.

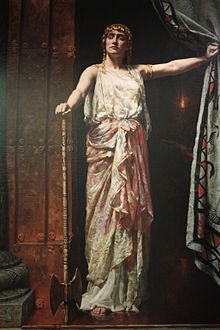

Medea is an ancient Greek tragedy written by Euripides. It is based upon the myth of Jason and Medea and was first produced in 431 BC as part of a trilogy; the two other plays have not survived. The plot centers on the actions of Medea, a former princess of the kingdom of Colchis, and the wife of Jason; she finds her position in the Greek world threatened as Jason leaves her for a Greek princess of Corinth. Medea takes vengeance on Jason by murdering his new wife and her own two sons, after which she escapes to Athens to start a new life.

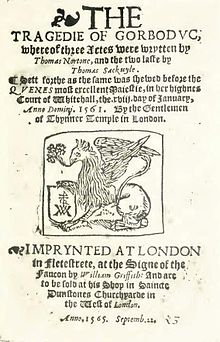

Revenge tragedy is a theatrical genre, in which the principal theme is revenge and revenge's fatal consequences. Formally established by American educator Ashley H. Thorndike in his 1902 article "The Relations of Hamlet to Contemporary Revenge Plays," a revenge tragedy documents the progress of the protagonist's revenge plot and often leads to the demise of both the murderers and the avenger himself.

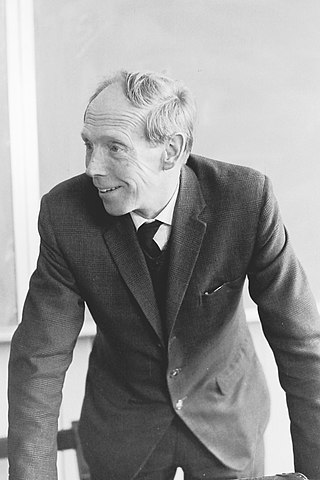

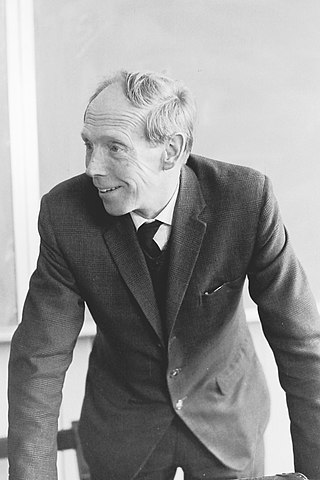

Philip Humphrey Vellacott was an English classical scholar, known for his numerous translations of Greek tragedy.

The Cambridge Greek Play is a play performed in Ancient Greek by students and alumni of the University of Cambridge, England. The event is held once every three years and is a tradition which started in 1882 with the Ajax of Sophocles.

Phaedra is a Roman tragedy written by philosopher and dramatist Lucius Annaeus Seneca before 54 A.D. Its 1,280 lines of verse tell the story of Phaedra, wife of King Theseus of Athens and her consuming lust for her stepson Hippolytus. Based on Greek mythology and the tragedy Hippolytus by Euripides, Seneca's Phaedra is one of several artistic explorations of this tragic story. Seneca portrays Phaedra as self-aware and direct in the pursuit of her stepson, while in other treatments of the myth, she is more of a passive victim of fate. This Phaedra takes on the scheming nature and the cynicism often assigned to the nurse character.

Phrike is the spirit of horror in Greek mythology. Her name literally means "tremor, shivering", and has the same stem as the verb φρίττω (phrittō) "to tremble". The term "Phrike" is widely used in tragedy.

Edith Hall, is a British scholar of classics, specialising in ancient Greek literature and cultural history, and professor in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Durham University. She is a Fellow of the British Academy. From 2006 until 2011 she held a Chair at Royal Holloway, University of London, where she founded and directed the Centre for the Reception of Greece and Rome until November 2011. She resigned over a dispute regarding funding for classics after leading a public campaign, which was successful, to prevent cuts to or the closure of the Royal Holloway Classics department. Until 2022, she was a professor at the Department of Classics at King's College London. She also co-founded and is Consultant Director of the Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama at Oxford University, Chair of the Gilbert Murray Trust, and Judge on the Stephen Spender Prize for poetry translation. Her prizewinning doctoral thesis was awarded at Oxford. In 2012 she was awarded a Humboldt Research Prize to study ancient Greek theatre in the Black Sea, and in 2014 she was elected to the Academy of Europe. She lives in Cambridgeshire.

Antilabe is a rhetorical technique in verse drama or closet drama, in which a single verse line of dialogue is distributed on two or more characters, voices, or entities. The verse usually maintains its metric integrity, while the line fragments spoken by the characters may or may not be complete sentences. In the layout of the text the line fragments following the first one are often indented to show the unity of the verse line.

BRUTUS:

CLITUS:

Medea is a fabula crepidata of about 1027 lines of verse written by Seneca the Younger. It is generally considered to be the strongest of his earlier plays. It was written around 50 CE. The play is about the vengeance of Medea against her betraying husband Jason and King Creon. The leading role, Medea, delivers over half of the play's lines. Medea addresses many themes, one being that the title character represents "payment" for humans' transgression of natural laws. She was sent by the gods to punish Jason for his sins. Another theme is her powerful voice that cannot be silenced, not even by King Creon.

The Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama (APGRD) is a research project based at the University of Oxford, England, founded in 1996 by Edith Hall and Oliver Taplin. The current director is Fiona Macintosh.

The Oxford University Classical Drama Society (OUCDS) is the funding body behind the triennial Oxford Greek Play, an institution that has lasted for over 130 years.

Philoctetes is a tragedy by the Athenian poet Euripides. It was probably first produced in 431 BCE at the Dionysia in a tetralogy that included the extant Medea and was awarded third prize. It is now lost except for a few fragments. Much of what we know of the plot is from the writings of Dio Chrysostom, who compared the Philoctetes plays of Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles and also paraphrased the beginning of Euripides' play.

Thyestes is a first century AD fabula crepidata of approximately 1112 lines of verse by Lucius Annaeus Seneca, which tells the story of Thyestes, who unwittingly ate his own children who were slaughtered and served at a banquet by his brother Atreus. As with most of Seneca's plays, Thyestes is based upon an older Greek version with the same name by Euripides.

Fiona Macintosh is Professor of Classical Reception at the University of Oxford, Director of the Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama, Curator of the Ioannou Centre, and a Fellow of St Hilda's College, Oxford.

John Gordon Fitch is a classical scholar. He works chiefly on Roman poetry, especially Lucretius and the dramas of Seneca, and his interests also include Greek and Roman texts on agriculture and medicine. He is a professor Emeritus at the University of Victoria.