Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, marine navigation, aeronautic navigation, and space navigation.

The g factor is a construct developed in psychometric investigations of cognitive abilities and human intelligence. It is a variable that summarizes positive correlations among different cognitive tasks, reflecting the fact that an individual's performance on one type of cognitive task tends to be comparable to that person's performance on other kinds of cognitive tasks. The g factor typically accounts for 40 to 50 percent of the between-individual performance differences on a given cognitive test, and composite scores based on many tests are frequently regarded as estimates of individuals' standing on the g factor. The terms IQ, general intelligence, general cognitive ability, general mental ability, and simply intelligence are often used interchangeably to refer to this common core shared by cognitive tests. However, the g factor itself is a mathematical construct indicating the level of observed correlation between cognitive tasks. The measured value of this construct depends on the cognitive tasks that are used, and little is known about the underlying causes of the observed correlations.

Self-handicapping is a cognitive strategy by which people avoid effort in the hopes of keeping potential failure from hurting self-esteem. It was first theorized by Edward E. Jones and Steven Berglas, according to whom self-handicaps are obstacles created, or claimed, by the individual in anticipation of failing performance.

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, spatial memory is a form of memory responsible for the recording and recovery of information needed to plan a course to a location and to recall the location of an object or the occurrence of an event. Spatial memory is necessary for orientation in space. Spatial memory can also be divided into egocentric and allocentric spatial memory. A person's spatial memory is required to navigate around a familiar city. A rat's spatial memory is needed to learn the location of food at the end of a maze. In both humans and animals, spatial memories are summarized as a cognitive map.

Metacognition is an awareness of one's thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning "beyond", or "on top of". Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one's ways of thinking and knowing when and how to use particular strategies for problem-solving. There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) knowledge about cognition and (2) regulation of cognition. A metacognitive model differs from other scientific models in that the creator of the model is per definition also enclosed within it. Scientific models are often prone to distancing the observer from the object or field of study whereas a metacognitive model in general tries to include the observer in the model.

In psychology, self-efficacy is an individual's belief in their capacity to act in the ways necessary to reach specific goals. The concept was originally proposed by the psychologist Albert Bandura.

Mental rotation is the ability to rotate mental representations of two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects as it is related to the visual representation of such rotation within the human mind. There is a relationship between areas of the brain associated with perception and mental rotation. There could also be a relationship between the cognitive rate of spatial processing, general intelligence and mental rotation.

Spatial visualization ability or visual-spatial ability is the ability to mentally manipulate 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional figures. It is typically measured with simple cognitive tests and is predictive of user performance with some kinds of user interfaces.

Mathematical anxiety, also known as math phobia, is a feeling of tension and anxiety that interferes with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in daily life and academic situations.

Topographical disorientation is the inability to orient oneself in one's surroundings, sometimes as a result of focal brain damage. This disability may result from the inability to make use of selective spatial information or to orient by means of specific cognitive strategies such as the ability to form a mental representation of the environment, also known as a cognitive map. It may be part of a syndrome known as visuospatial dysgnosia.

Spatial cognition is the acquisition, organization, utilization, and revision of knowledge about spatial environments. It is most about how animals including humans behave within space and the knowledge they built around it, rather than space itself. These capabilities enable individuals to manage basic and high-level cognitive tasks in everyday life. Numerous disciplines work together to understand spatial cognition in different species, especially in humans. Thereby, spatial cognition studies also have helped to link cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Scientists in both fields work together to figure out what role spatial cognition plays in the brain as well as to determine the surrounding neurobiological infrastructure.

The Mental Rotations Test is a test of spatial ability by Steven G. Vandenberg and Allan R. Kuse, first published in 1978. It has been used in hundreds of studies since then.

Sex differences in human intelligence have long been a topic of debate among researchers and scholars. It is now recognized that there are no significant sex differences in average IQ, though particular subtypes of intelligence vary somewhat between sexes.

Daniel R. Montello is an American geographer and professor at the Department of Geography of the University of California Santa Barbara, and at its Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, known for his work on geovisualization and cognitive geography.

Sex differences in cognition are widely studied in the current scientific literature. Biological and genetic differences in combination with environment and culture have resulted in the cognitive differences among males and females. Among biological factors, hormones such as testosterone and estrogen may play some role mediating these differences. Among differences of diverse mental and cognitive abilities, the largest or most well known are those relating to spatial abilities, social cognition and verbal skills and abilities.

Spatial ability or visuo-spatial ability is the capacity to understand, reason, and remember the visual and spatial relations among objects or space.

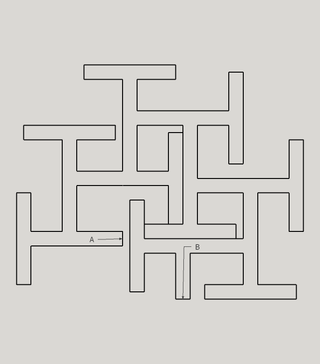

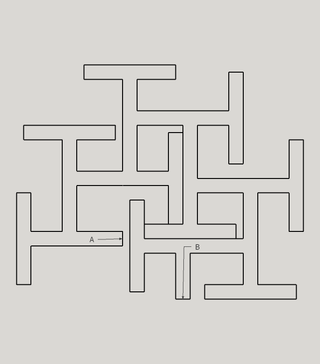

The Cincinnati Water Maze (CWM) is a type of water maze. Water mazes are experimental equipment used in laboratories; they are mazes that are partially filled with water, and rodents are put in them to be observed and timed as they make their way through the maze. Generally two sets of rodents are put through the maze, one that has been treated, and another that has not, and the results are compared. The experimenter uses this type of maze to learn about the subject's cognitive or emotional processes.

Mary Hegarty is an Irish–American psychologist who is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research considers spatial thinking in complex processes. She is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Spatial anxiety is a sense of anxiety an individual experiences while processing environmental information contained in one's geographical space, with the purpose of navigation and orientation through that space. Spatial anxiety is also linked to the feeling of stress regarding the anticipation of a spatial-content related performance task. Particular cases of spatial anxiety can result in a more severe form of distress, as in agoraphobia.

Wayfinding has been used in the context of architecture to refer to the user experience of orientation and navigating within the built environment.