The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War fought on 9 August 48 BC near Pharsalus in Central Greece. Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the Roman Republic under the command of Pompey. Pompey had the backing of a majority of Roman senators and his army significantly outnumbered the veteran Caesarian legions.

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a general and statesman of the Roman Republic. He played a significant role in the transformation of Rome from republic to empire. Early in his career, he was a partisan and protégé of the Roman general and dictator Sulla; later, he became the political ally, and finally the enemy, of Julius Caesar.

This article concerns the period 49 BC – 40 BC.

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was a general and politician of ancient Rome in the 1st century BC.

The Battle of Dyrrachium took place from April to late July 48 BC near the city of Dyrrachium, modern day Durrës in what is now Albania. It was fought between Gaius Julius Caesar and an army led by Gnaeus Pompey during Caesar's civil war.

Publius Attius Varus was the Roman governor of Africa during the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. He declared against Caesar, and initially fought Gaius Scribonius Curio, who was sent against him in 49 BC.

Caesar's civil war was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Gaius Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey), respectively. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the republic on his expected return to Rome on the expiration of his governorship in Gaul.

The siege of Massilia, including two naval engagements, was an episode of Caesar's Civil War, fought in 49 BC between forces loyal to the Optimates and a detachment of Caesar's army. The siege was conducted by Gaius Trebonius, one of Caesar's senior legates, while the naval operations were in the capable hands of Decimus Brutus, Caesar's naval expert.

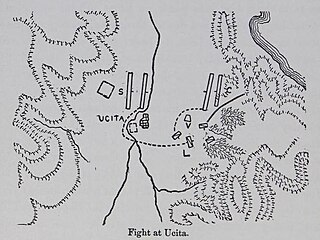

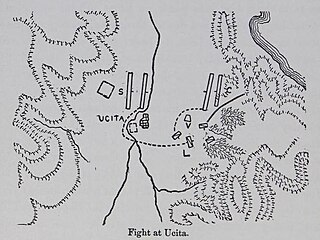

The Battle of Utica in Caesar's Civil War was fought between Julius Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio and Pompeian legionaries commanded by Publius Attius Varus supported by Numidian cavalry and foot soldiers sent by King Juba I of Numidia. Curio defeated the Pompeians and Numidians and drove Varus back into the town of Utica.

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, consul in 54 BC, was an enemy of Julius Caesar and a strong supporter of the aristocratic party in the late Roman Republic.

The Alexandrian war, also called the Alexandrine war, was a phase of Caesar's civil war in which Julius Caesar involved himself in an Egyptian dynastic struggle. Caesar attempted to mediate a succession dispute between Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII and exact repayment of certain Egyptian debts.

The siege of Corfinium was the first significant military confrontation of Caesar's Civil War. Undertaken in February 49 BC, it saw the forces of Gaius Julius Caesar's Populares besiege the Italian city of Corfinium, which was held by a force of Optimates under the command of Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. The siege lasted only a week, after which the defenders surrendered themselves to Caesar. This bloodless victory was a significant propaganda coup for Caesar and hastened the retreat of the main Optimate force from Italia, leaving the Populares in effective control of the entire peninsula.

The Battle of Tauroento was a naval battle fought off the coast of Tauroento during Caesar's Civil War. Following a successful naval battle outside Massilia, the Caesarian fleet commanded by Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus once again came into conflict with the Massiliot fleet and a Pompeian relief fleet led by Quintus Nasidius on 31 July 49 BC. Despite being significantly outnumbered, the Caesarians prevailed and the Siege of Massilia was able to continue leading to the eventual surrender of the city.

The siege of Gomphi was a brief military confrontation during Caesar's Civil War. Following defeat at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, the men of Gaius Julius Caesar besieged the Thessalian city of Gomphi. The city fell in a few hours and Caesar's men were allowed to sack Gomphi.

The Battle of Hippo Regius was a naval encounter during Caesar's Civil War which occurred off the coast of the African city of Hippo Regius in 46 BC. Metellus Scipio and a number of influential senators from the Optimate faction were fleeing the disastrous Battle of Thapsus when their fleet was intercepted and destroyed by Publius Sittius, a mercenary commander in the employ of the Mauretanian king Bogud, an ally of Gaius Julius Caesar's. Scipio committed suicide and all of the other senators were killed during the battle.

The siege of Curicta was a military confrontation that took place during the early stages of Caesar's Civil War. Occurring in 49 BC, it saw a significant force of Populares commanded by Gaius Antonius besieged on the island of Curicta by an Optimate fleet under Lucius Scribonius Libo and Marcus Octavius. It immediately followed and was the result of a naval defeat by Publius Cornelius Dolabella and Antonius eventually capitulated under prolonged siege. These two defeats were some of the most significant suffered by the Populares during the civil war.

The Battle off Carteia was a minor naval battle during the latter stages of Caesar's civil war won by the Caesarians led by Caesar's legate Gaius Didius against the Pompeians led by Publius Attius Varus.

The siege of Corduba was an engagement near the end of Caesar's Civil War, in which Julius Caesar had besieged the city of Corduba after Sextus Pompey, Son of Pompey Magnus had fled the city leaving Annio Scapula in charge. Caesar stormed the city and 22,000 people died.

Caesar's invasion of Macedonia occurred as part of Caesar's civil war, starting with his landing near Paeleste on the coast of Epirus, and continuing until he forced Pompey to flight after the Battle of Pharsalus.

Lucius Vibullius Rufus was a Roman politician and general who lived during the 1st century BC. He sided with Pompey during Caesar's Civil War.