A polymer is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life. Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function. Polymers, both natural and synthetic, are created via polymerization of many small molecules, known as monomers. Their consequently large molecular mass, relative to small molecule compounds, produces unique physical properties including toughness, high elasticity, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form amorphous and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals.

In polymer chemistry, polymerization, or polymerisation, is a process of reacting monomer molecules together in a chemical reaction to form polymer chains or three-dimensional networks. There are many forms of polymerization and different systems exist to categorize them.

In chemistry, the dispersity is a measure of the heterogeneity of sizes of molecules or particles in a mixture. A collection of objects is called uniform if the objects have the same size, shape, or mass. A sample of objects that have an inconsistent size, shape and mass distribution is called non-uniform. The objects can be in any form of chemical dispersion, such as particles in a colloid, droplets in a cloud, crystals in a rock, or polymer macromolecules in a solution or a solid polymer mass. Polymers can be described by molecular mass distribution; a population of particles can be described by size, surface area, and/or mass distribution; and thin films can be described by film thickness distribution.

Chain-growth polymerization (AE) or chain-growth polymerisation (BE) is a polymerization technique where unsaturated monomer molecules add onto the active site on a growing polymer chain one at a time. There are a limited number of these active sites at any moment during the polymerization which gives this method its key characteristics.

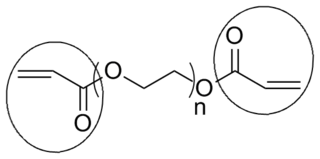

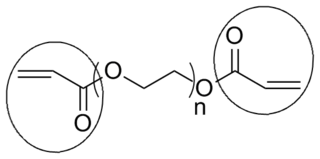

End groups are an important aspect of polymer synthesis and characterization. In polymer chemistry, they are functional groups that are at the very ends of a macromolecule or oligomer (IUPAC). In polymer synthesis, like condensation polymerization and free-radical types of polymerization, end-groups are commonly used and can be analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to determine the average length of the polymer. Other methods for characterization of polymers where end-groups are used are mass spectrometry and vibrational spectrometry, like infrared and raman spectroscopy. These groups are important for the analysis of polymers and for grafting to and from a polymer chain to create a new copolymer. One example of an end group is in the polymer poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate where the end-groups are circled.

The molar mass distribution describes the relationship between the number of moles of each polymer species (Ni) and the molar mass (Mi) of that species. In linear polymers, the individual polymer chains rarely have exactly the same degree of polymerization and molar mass, and there is always a distribution around an average value. The molar mass distribution of a polymer may be modified by polymer fractionation.

In polymer chemistry, free-radical polymerization (FRP) is a method of polymerization by which a polymer forms by the successive addition of free-radical building blocks. Free radicals can be formed by a number of different mechanisms, usually involving separate initiator molecules. Following its generation, the initiating free radical adds (nonradical) monomer units, thereby growing the polymer chain.

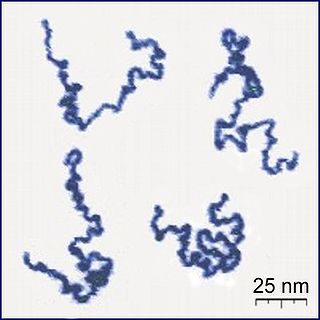

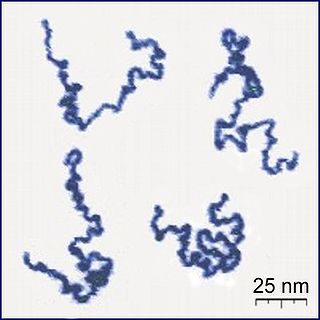

In polymer chemistry, anionic addition polymerization is a form of chain-growth polymerization or addition polymerization that involves the polymerization of monomers initiated with anions. The type of reaction has many manifestations, but traditionally vinyl monomers are used. Often anionic polymerization involves living polymerizations, which allows control of structure and composition.

The degree of polymerization, or DP, is the number of monomeric units in a macromolecule or polymer or oligomer molecule.

Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) is an example of a reversible-deactivation radical polymerization. Like its counterpart, ATRA, or atom transfer radical addition, ATRP is a means of forming a carbon-carbon bond with a transition metal catalyst. Polymerization from this method is called atom transfer radical addition polymerization (ATRAP). As the name implies, the atom transfer step is crucial in the reaction responsible for uniform polymer chain growth. ATRP was independently discovered by Mitsuo Sawamoto and by Krzysztof Matyjaszewski and Jin-Shan Wang in 1995.

Flory–Huggins solution theory is a lattice model of the thermodynamics of polymer solutions which takes account of the great dissimilarity in molecular sizes in adapting the usual expression for the entropy of mixing. The result is an equation for the Gibbs free energy change for mixing a polymer with a solvent. Although it makes simplifying assumptions, it generates useful results for interpreting experiments.

In step-growth polymerization, the Carothers equation gives the degree of polymerization, Xn, for a given fractional monomer conversion, p.

Polyester is a category of polymers that contain the ester functional group in every repeat unit of their main chain. As a specific material, it most commonly refers to a type called polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polyesters include naturally occurring chemicals, such as in plants and insects, as well as synthetics such as polybutyrate. Natural polyesters and a few synthetic ones are biodegradable, but most synthetic polyesters are not. Synthetic polyesters are used extensively in clothing.

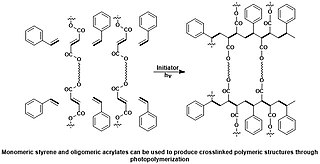

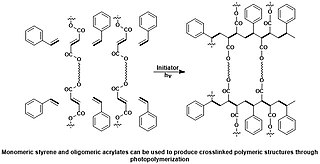

A photopolymer or light-activated resin is a polymer that changes its properties when exposed to light, often in the ultraviolet or visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. These changes are often manifested structurally, for example hardening of the material occurs as a result of cross-linking when exposed to light. An example is shown below depicting a mixture of monomers, oligomers, and photoinitiators that conform into a hardened polymeric material through a process called curing.

In polymer chemistry, a repeat unit or repeating unit is a part of a polymer whose repetition would produce the complete polymer chain by linking the repeat units together successively along the chain, like the beads of a necklace.

In polymer chemistry, gelation is the formation of a gel from a system with polymers. Branched polymers can form links between the chains, which lead to progressively larger polymers. As the linking continues, larger branched polymers are obtained and at a certain extent of the reaction links between the polymer result in the formation of a single macroscopic molecule. At that point in the reaction, which is defined as gel point, the system loses fluidity and viscosity becomes very large. The onset of gelation, or gel point, is accompanied by a sudden increase in viscosity. This "infinite" sized polymer is called the gel or network, which does not dissolve in the solvent, but can swell in it.

In chemistry, cationic polymerization is a type of chain growth polymerization in which a cationic initiator transfers charge to a monomer which then becomes reactive. This reactive monomer goes on to react similarly with other monomers to form a polymer. The types of monomers necessary for cationic polymerization are limited to alkenes with electron-donating substituents and heterocycles. Similar to anionic polymerization reactions, cationic polymerization reactions are very sensitive to the type of solvent used. Specifically, the ability of a solvent to form free ions will dictate the reactivity of the propagating cationic chain. Cationic polymerization is used in the production of polyisobutylene and poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK).

Polysilazanes are polymers in which silicon and nitrogen atoms alternate to form the basic backbone. Since each silicon atom is bound to two separate nitrogen atoms and each nitrogen atom to two silicon atoms, both chains and rings of the formula occur. can be hydrogen atoms or organic substituents. If all substituents R are H atoms, the polymer is designated as Perhydropolysilazane, Polyperhydridosilazane, or Inorganic Polysilazane ([H2Si–NH]n). If hydrocarbon substituents are bound to the silicon atoms, the polymers are designated as Organopolysilazanes. Molecularly, polysilazanes are isoelectronic with and close relatives to Polysiloxanes (silicones).

Reversible deactivation radical polymerizations (RDRPs) are members of the class of reversible deactivation polymerizations which exhibit much of the character of living polymerizations, but cannot be categorized as such as they are not without chain transfer or chain termination reactions. Several different names have been used in literature, which are:

Flory–Stockmayer theory is a theory governing the cross-linking and gelation of step-growth polymers. The Flory-Stockmayer theory represents an advancement from the Carothers equation, allowing for the identification of the gel point for polymer synthesis not at stoichiometric balance. The theory was initially conceptualized by Paul Flory in 1941 and then was further developed by Walter Stockmayer in 1944 to include cross-linking with an arbitrary initial size distribution. The Flory-Stockmayer theory was the first theory investigating percolation processes. Flory–Stockmayer theory is a special case of random graph theory of gelation.