The Benjamin Franklin class of US ballistic missile submarines were in Navy service from the 1960s–2000s. The class was an evolutionary development from the earlier James Madison class of fleet ballistic missile submarine. Having quieter machinery and other improvements, it is considered a separate class. A subset of this class is the re-engineered 640 class starting with USS George C. Marshall. The primary difference was that they were built under the new SUBSAFE rules after the loss of USS Thresher, earlier boats of the class had to be retrofitted to meet SUBSAFE requirements. The Benjamin Franklin class, together with the George Washington, Ethan Allen, Lafayette, and James Madison classes, comprised the "41 for Freedom" that was the Navy's primary contribution to the nuclear deterrent force through the late 1980s. This class and the James Madison class are combined with the Lafayettes in some references.

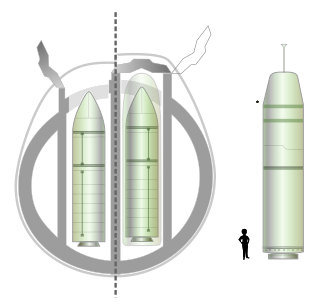

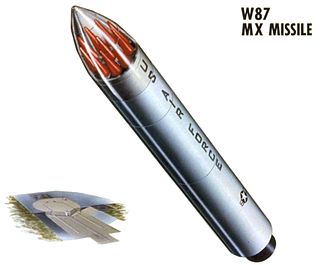

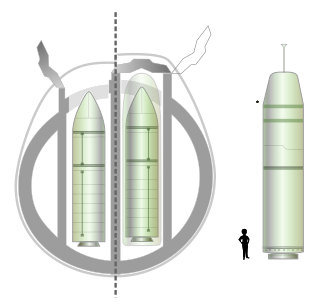

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than 5,500 kilometres (3,400 mi), primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery. Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons can also be delivered with varying effectiveness, but have never been deployed on ICBMs. Most modern designs support multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRVs), allowing a single missile to carry several warheads, each of which can strike a different target. The United States, Russia, China, France, India, the United Kingdom, Israel, and North Korea are the only countries known to have operational ICBMs.

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

The UGM-73 Poseidon missile was the second US Navy nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) system, powered by a two-stage solid-fuel rocket. It succeeded the UGM-27 Polaris beginning in 1972, bringing major advances in warheads and accuracy. It was followed by Trident I in 1979, and Trident II in 1990.

In nuclear strategy, a first strike or preemptive strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the attacking country can survive the weakened retaliation while the opposing side is left unable to continue war. The preferred methodology is to attack the opponent's strategic nuclear weapon facilities, command and control sites, and storage depots first. The strategy is called counterforce.

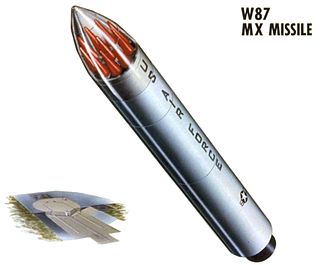

A multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) is an exoatmospheric ballistic missile payload containing several warheads, each capable of being aimed to hit a different target. The concept is almost invariably associated with intercontinental ballistic missiles carrying thermonuclear warheads, even if not strictly being limited to them. An intermediate case is the multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) missile which carries several warheads which are dispersed but not individually aimed. All nuclear-weapon states except Pakistan and North Korea are currently confirmed to have deployed MIRV missile systems. Israel is suspected to possess or be in the process of developing MIRVs.

Chevaline was a system to improve the penetrability of the warheads used by the British Polaris nuclear weapons system. Devised as an answer to the improved Soviet anti-ballistic missile defences around Moscow, the system increased the probability that at least one warhead would penetrate Moscow's anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defences, something which the Royal Navy's earlier UGM-27 Polaris re-entry vehicles (RVs) were thought to be unlikely to do.

A ballistic missile submarine is a submarine capable of deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with nuclear warheads. These submarines became a major weapon system in the Cold War because of their nuclear deterrence capability. They can fire missiles thousands of kilometers from their targets, and acoustic quieting makes them difficult to detect, thus making them a survivable deterrent in the event of a first strike and a key element of the mutual assured destruction policy of nuclear deterrence. The deployment of ballistic missile submarines is dominated by the United States and Russia. Smaller numbers are in service with France, the United Kingdom, China and India; North Korea is also suspected to have an experimental submarine that is diesel-electric powered.

The George Washington class was a class of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines deployed by the United States Navy. George Washington, along with the later Ethan Allen, Lafayette, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin classes, comprised the "41 for Freedom" group of submarines that represented the Navy's main contribution to the nuclear deterrent force through the late 1980s.

The Yankee class, Soviet designations Project 667A Navaga (navaga) and Project 667AU Nalim (burbot) for the basic Yankee-I, were a family of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines built in the Soviet Union for the Soviet Navy. In total, 34 units were built: 24 in Severodvinsk for the Northern Fleet and the remaining 10 in Komsomolsk-on-Amur for the Pacific Fleet. Two Northern Fleet units were later transferred to the Pacific.

The Lafayette class of submarine was an evolutionary development from the Ethan Allen class of fleet ballistic missile submarine, slightly larger and generally improved. This class, together with the George Washington, Ethan Allen, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin classes, composed the "41 for Freedom," the Navy's primary contribution to the nuclear deterrent force through the late 1980s. The James Madison and Benjamin Franklin classes are combined with the Lafayettes in some references.

The James Madison class of submarine was an evolutionary development from the Lafayette class of fleet ballistic missile submarine. They were identical to the Lafayettes except for being initially designed to carry the Polaris A-3 missile instead of the earlier A-2. This class, together with the George Washington, Ethan Allen, Lafayette, and Benjamin Franklin classes, composed the "41 for Freedom" that was the Navy's primary contribution to the nuclear deterrent force through the late 1980s. This class and the Benjamin Franklin class are combined with the Lafayettes in some references.

The M45 SLBM was a French Navy submarine-launched ballistic missile Forty-eight M45 were in commission in the Force océanique stratégique, the submarine nuclear deterrent component of the French Navy. The missiles, derived from the M4, were produced by Aérospatiale. Initially, an ICBM land-based version was considered, but these plans were discarded in 1996 to favour an all-naval deployment.

The UGM-133A Trident II, or Trident D5 is a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), built by Lockheed Martin Space in Sunnyvale, California, and deployed with the United States and Royal Navy. It was first deployed in March 1990, and remains in service. The Trident II Strategic Weapons System is an improved SLBM with greater accuracy, payload, and range than the earlier Trident C-4. It is a key element of the U.S. strategic nuclear triad and strengthens U.S. strategic deterrence. The Trident II is considered to be a durable sea-based system capable of engaging many targets. It has payload flexibility that can accommodate various treaty requirements, such as New START. The Trident II's increased payload allows nuclear deterrence to be accomplished with fewer submarines, and its high accuracy—approaching that of land-based missiles—enables it to be used as a first strike weapon.

A submarine-launched cruise missile (SLCM) is a cruise missile that is launched from a submarine. Current versions are typically standoff weapons known as land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs), which are used to attack predetermined land targets with conventional or nuclear payloads. Anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) are also used, and some submarine-launched cruise missiles have variants for both functions.

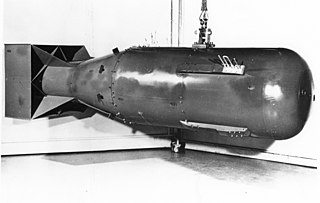

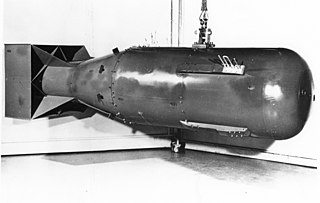

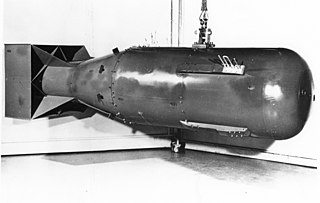

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

A nuclear triad is a three-pronged military force structure of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and strategic bombers with nuclear bombs and missiles. Countries build nuclear triads to eliminate an enemy's ability to destroy a nation's nuclear forces in a first-strike attack, which preserves their own ability to launch a second strike and therefore increases their nuclear deterrence.

In nuclear strategy, a counterforce target is one that has a military value, such as a launch silo for intercontinental ballistic missiles, an airbase at which nuclear-armed bombers are stationed, a homeport for ballistic missile submarines, or a command and control installation.

STRAT-X, or Strategic-Experimental, was a U.S. government-sponsored study conducted during 1966 and 1967 that comprehensively analyzed the potential future of the U.S. nuclear deterrent force. At the time, the Soviet Union was making significant strides in nuclear weapons delivery, and also constructing anti-ballistic missile defenses to protect strategic facilities. To address a potential technological gap between the two superpowers, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara entrusted the classified STRAT-X study to the Institute for Defense Analyses, which compiled a twenty-volume report in nine months. The report looked into more than one hundred different weapons systems, ultimately resulting in the MGM-134 Midgetman and LGM-118 Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missiles, the Ohio-class submarines, and the Trident submarine-launched ballistic missiles, among others. Journalists have regarded STRAT-X as a major influence on the course of U.S. nuclear policy.