Titus Maccius Plautus was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by Livius Andronicus, the innovator of Latin literature. The word Plautine refers to both Plautus's own works and works similar to or influenced by his.

The Winter's Tale is a play by William Shakespeare originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Although it was grouped among the comedies, many modern editors have relabelled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Some critics consider it to be one of Shakespeare's "problem plays" because the first three acts are filled with intense psychological drama, while the last two acts are comic and supply a happy ending.

The Two Gentlemen of Verona is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1589 and 1593. It is considered by some to be Shakespeare's first play, and is often seen as showing his first tentative steps in laying out some of the themes and motifs with which he would later deal in more detail; for example, it is the first of his plays in which a heroine dresses as a boy. The play deals with the themes of friendship and infidelity, the conflict between friendship and love, and the foolish behaviour of people in love. The highlight of the play is considered by some to be Launce, the clownish servant of Proteus, and his dog Crab, to whom "the most scene-stealing non-speaking role in the canon" has been attributed.

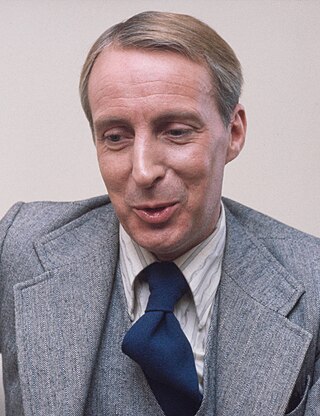

Denis Clifford Quilley, OBE was an English actor and singer. From a family with no theatrical connections, Quilley was determined from an early age to become an actor. He was taken on by the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in his teens, and after a break for compulsory military service he began a West End career in 1950, succeeding Richard Burton in The Lady's Not For Burning. In the 1950s he appeared in revue, musicals, operetta and on television as well as in classic and modern drama in the theatre.

Twelfth Night, or What You Will is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Viola and Sebastian, who are separated in a shipwreck. Viola falls in love with the Duke Orsino, who in turn is in love with Countess Olivia. Upon meeting Viola, Countess Olivia falls in love with her thinking she is a man.

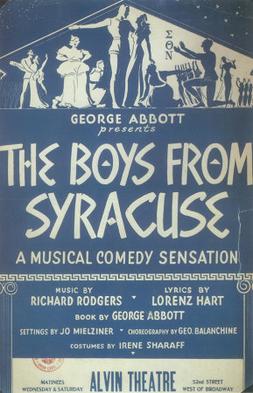

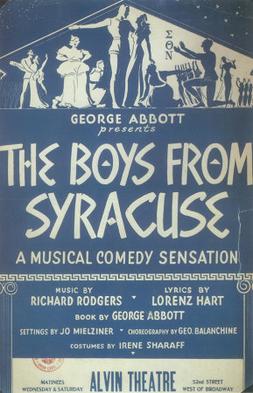

The Boys from Syracuse is a musical with music by Richard Rodgers and lyrics by Lorenz Hart, based on William Shakespeare's play The Comedy of Errors, as adapted by librettist George Abbott. The score includes swing and other contemporary rhythms of the 1930s. The show was the first musical based on a Shakespeare play. The Comedy of Errors was itself loosely based on a Roman play, The Menaechmi, or the Twin Brothers, by Plautus.

Ian William Richardson was a British actor from Edinburgh, Scotland.

Roger Rees was a Welsh actor and director, widely known for his stage work. He won an Olivier Award and a Tony Award for his performance as the lead in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. He also received Obie Awards for his role in The End of the Day and as co-director of Peter and the Starcatcher. Rees was posthumously inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in November 2015.

Geoffrey Hutchings was an English stage, film and television actor.

Forbes (Robertson) Masson is a Scottish actor and writer. He is an Associate Artist with the Royal Shakespeare Company. He is best known for his roles in classical theatre, musicals, comedies, and appearances in London's West End. He is also known for his comedy partnership with Alan Cumming. Masson and Cumming wrote The High Life, a Scottish situation comedy in which they play the lead characters, Steve McCracken and Sebastian Flight. Characters McCracken and Flight were heavily based on Victor and Barry, famous Scottish comedy alter-egos of Masson and Cumming. Masson also stars in the 2021 film The Road Dance, set on the Isle of Lewis as the Reverend MacIver.

Nickolas Andrew Halliwell Grace is an English actor known for his roles on television, including Anthony Blanche in the acclaimed ITV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited, and the Sheriff of Nottingham in the 1980s series Robin of Sherwood. Grace also played Dorien Green's husband Marcus Green in the 1990s British comedy series Birds of a Feather.

Simon Coates is a British actor who has worked extensively with the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, with whom he has appeared internationally, working with directors such as Sir Richard Eyre, Robert Lepage, Howard Davies, William Gaskill, Sir David Hare, Declan Donnellan, Tim Supple, Sir Tom Stoppard, David Farr, Lindsay Posner, Sean Holmes, Katie Mitchell, Indhu Rubasingham, Phyllida Lloyd, Thea Sharrock, Dame Vanessa Redgrave, Sir Trevor Nunn, Robert Icke, Simon Godwin, James Dacre, Rupert Goold, Sir Gregory Doran, Blanche McIntyre and Sir Michael Boyd.

Alfred Charles Kay and better known by his stage name Charles Kay is an English actor.

The Shakespearean fool is a recurring character type in the works of William Shakespeare.

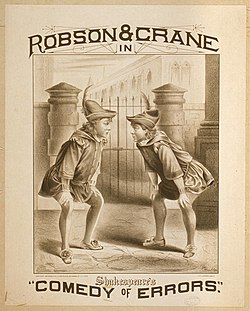

The Comedy of Errors is a musical with a book and lyrics by Trevor Nunn and music by Guy Woolfenden. It is based on the William Shakespeare play, The Comedy of Errors, which had previously been adapted for the musical stage as The Boys from Syracuse by Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart and George Abbott in 1938. The London production won the Olivier Award for Best New Musical in 1977.

The Boys from Syracuse is a 1940 American musical film directed by A. Edward Sutherland, based on the 1938 stage musical by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, which in turn was loosely based on the play The Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards; one for Best Visual Effects and one for Best Art Direction.

Thomas Hull (1728–1808) was an English actor and dramatist.

The Taming of the Shrew in performance has had an uneven history. Popular in Shakespeare's day, the play fell out of favour during the seventeenth century, when it was replaced on the stage by John Lacy's Sauny the Scott. The original Shakespearean text was not performed at all during the eighteenth century, with David Garrick's adaptation Catharine and Petruchio dominating the stage. After over two hundred years without a performance, the play returned to the British stage in 1844, the last Shakespeare play restored to the repertory. However, it was only in the 1890s that the dominance of Catharine and Petruchio began to wane, and productions of The Shrew become more regular. Moving into the twentieth century, the play's popularity increased considerably, and it became one of Shakespeare's most frequently staged plays, with productions taking place all over the world. This trend has continued into the twenty-first century, with the play as popular now as it was when first written.

Dan Chameroy is a Canadian actor.