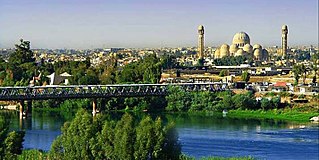

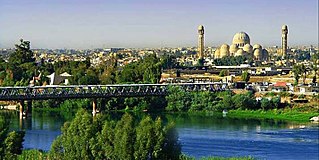

Nineveh Governorate, to be better called Ninawa Governorate, is a governorate in northern Iraq. It has an area of 37,323 km2 (14,410 sq mi) and an estimated population of 2,453,000 people as of 2003. Its largest city and provincial capital is Mosul, which lies across the Tigris river from the ruins of ancient Nineveh. Before 1976, it was called Mosul Province and included the present-day Dohuk Governorate. The second largest city is Tal Afar, which had an almost exclusively Turkmen population.

Sinjar is a town in the Sinjar District of the Nineveh Governorate in northern Iraq. It is located about five kilometers south of the Sinjar Mountains. Its population in 2013 was estimated at 88,023, and is predominantly Yazidi.

The Sinjar District or the Shingal District is a district of the Nineveh Governorate. The district seat is the town of Sinjar. The district has two subdistricts, al-Shemal and al-Qayrawan. The district is one of two major population centers for Yazidis, the other being Shekhan District.

The genocide of Christians by the Islamic State involves the systematic mass murder of Christian minorities, within the regions of Iraq, Syria, Egypt and Libya controlled by the Islamic terrorist group Islamic State. Persecution of Christian minorities climaxed following the Syrian civil war and later by its spillover.

Vian Dakhil is a current member of the Iraqi parliament. She is the only Yazidi Kurd in the Iraqi Parliament.

The War in Iraq was an armed conflict between Iraq and its allies and the Islamic State which began in 2013 and ended in December 2017. Following December 2013, the insurgency escalated into a full-scale war following the conquest of Ramadi, Fallujah, Tikrit and other towns in the major areas of northern Iraq by the Islamic State. Between 4–9 June 2014, the city of Mosul was attacked and later captured, following that, former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki called for a national state of emergency on 10 June. However, despite the security crisis, Iraq's parliament did not allow Maliki to declare a state of emergency; many legislators boycotted the session because they opposed expanding the prime minister's powers. Ali Ghaidan, a former military commander in Mosul, accused al-Maliki of being the one who issued the order to withdraw from the city of Mosul. At its height, ISIL held 56,000 square kilometers of Iraqi territory, containing 4.5 million citizens.

Between 1 and 15 August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) expanded territory in northern Iraq under their control. In the region north and west from Mosul, the Islamic State conquered Zumar, Sinjar, Wana, Mosul Dam, Qaraqosh, Tel Keppe, Batnaya and Kocho, and in the region south and east of Mosul the towns Bakhdida, Karamlish, Bartella and Makhmour

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has employed sexual violence against women and men in a terroristic manner. Sexual violence, as defined by The World Health Organization includes “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.” ISIL has used sexual violence to undermine a sense of security within communities, and to raise funds through the sale of captives into sexual slavery.

The state of human rights in the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ISIS) is considered to be one of, if not, the worst in modern history and has been severely criticised by many political and religious organisations, and individuals. Islamic State policies included severe acts of genocide, torture and slavery. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) has stated that the Islamic State "seeks to subjugate civilians under its control and dominate every aspect of their lives through terror, indoctrination, and the provision of services to those who obey". ISIS actions of extreme criminality, terror, recruitment and other activities has been documented in the Middle East and several other regions around the world.

Nadia Murad Basee Taha is an Iraqi Yazidi human rights activist who lives in Germany. In 2014, she was kidnapped from her hometown Kocho and held by the Islamic State for three months.

A genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State was carried out in the Sinjar area of northern Iraq in the mid-2010s. The genocide led to the expulsion, flight and effective exile of the Yazidis. Thousands of Yazidi women and girls were forced into sexual slavery by ISIL, and thousands of Yazidi men were killed. About 5,000 thousand Yazidi civilians were killed during what has been called a "forced conversion campaign" carried out by ISIL in Northern Iraq. The genocide began after the withdrawal of Iraqi forces and Peshmerga, which left the Yazidis defenseless.

Yazda: Global Yazidi Organization, is a United States-based global Yazidi nonprofit, non-governmental organization (NGO) advocacy, aid, and relief organization. Yazda was established to support the Yazidi, especially in northern Iraq, specifically Sinjar and Nineveh Plain, and northeastern Syria, where the Yazidi community has, as part of a deliberate "military, economic, and political strategy," been the focus of a genocidal campaign by ISIL that included mass murder, the separation of families, forced religious conversions, forced marriages, sexual assault, physical assault, torture, kidnapping, and slavery.

Lamiya Haji Bashar is a Yazidi human rights activist. She was awarded the Sakharov Prize jointly with Nadia Murad in 2016.

Dalal Khario is a Yazidi woman from northern Iraq who fled to Germany after escaping from ISIS.

Farida Khalaf is the pen name of a Yazidi woman who was abducted by ISIS in 2014 and sold into slavery. She escaped to a refugee camp, and in 2016 published a book about her experience, The Girl Who Escaped ISIS.

Kocho is a village in Sinjar District, south of the Sinjar Mountains in the Nineveh Governorate of Iraq. It is considered one of the disputed territories of Northern Iraq and is populated by Yazidis. The village came to international attention in 2014 due to the genocide of Yazidis committed by the Islamic State.

The August 15, 2018 Turkish airstrikes on Sinjar were two airstrikes on İsmail Özden, a leading member of the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBŞ). Four others were killed in the airstrike.

Nadia’s Initiative is a nonprofit organization founded in 2018 by Nadia Murad that advocates for survivors of sexual violence and aims to rebuild communities in crisis. The launch of this organization was prompted by the Sinjar massacre, a religious persecution of the Yazidi people in Sinjar, Iraq by ISIS in 2014.

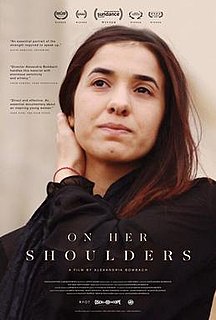

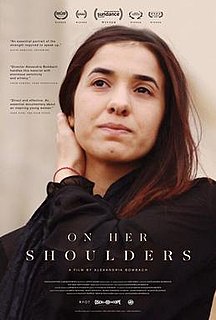

On Her Shoulders is a 2018 American documentary film. It was directed by Alexandria Bombach and produced by Hayley Pappas, Brock Williams and Elizabeth Schaeffer Brown under the banner of RYOT Films. The film follows Iraqi Yazidi human rights activist Nadia Murad on her three-month tour of Berlin, New York, and Canada, as she met with politicians and journalists to alert the world to the massacres and kidnapping happening in her native land. In 2014, at the age of 19, Murad had been kidnapped with hundreds of other women and girls by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) and held as a sex slave; she managed to escape. Also appearing in the film are Barack Obama, Ban Ki-moon, Murad Ismael, Simone Monasebian, Michelle Rempel, Borys Wrzesnewskyj, Ahmed Khudida Burjus, Amal Clooney, and Luis Moreno Ocampo.

The persecution of Yazidis has been ongoing since at least 637 CE. Yazidis are an endogamous and mostly Kurmanji-speaking minority, indigenous to Kurdistan. The Yazidi religion is regarded as "devil-worship" by Muslims and Islamists. Yazidis have been persecuted by the surrounding Muslims since the medieval ages, most notably by Safavids, Ottomans, neighbouring Muslim Arab and Kurdish tribes and principalities. After the 2014 Sinjar massacre of thousands of Yazidis by ISIL, which started the ethnic, cultural, and religious genocide of the Yazidis in Iraq, Yazidis still face discrimination from the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government.