Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree of accuracy. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation, the methods of gathering information, and the organizing literary styles.

Media bias occurs when journalists and news producers show bias in how they report and cover news. The term "media bias" implies a pervasive or widespread bias contravening of the standards of journalism, rather than the perspective of an individual journalist or article. The direction and degree of media bias in various countries is widely disputed.

A tabloid is a newspaper with a compact page size smaller than broadsheet. There is no standard size for this newspaper format.

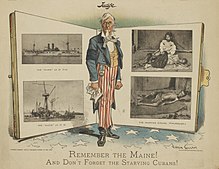

In journalism, yellow journalism and the yellow press are American newspapers that use eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations for increased sales. The English term is chiefly used in the US. In the United Kingdom, a similar term is tabloid journalism. Other languages, e.g. Russian, sometimes have terms derived from the American term. Yellow journalism emerged in the intense battle for readers by two newspapers in New York City in 1890s. It was not common in other cities.

Junk food news is a sardonic term for news stories that deliver "sensationalized, personalized, and homogenized inconsequential trivia", especially when such stories appear at the expense of serious investigative journalism. It implies a criticism of the mass media for disseminating news that, while not very nourishing, is "cheap to produce and profitable for media proprietors."

Media manipulation refers to orchestrated campaigns in which actors exploit the distinctive features of broadcasting mass communications or digital media platforms to mislead, misinform, or create a narrative that advance their interests and agendas.

The news media or news industry are forms of mass media that focus on delivering news to the general public. These include news agencies, newspapers, news magazines, news channels etc.

Infotainment, also called soft news as a way to distinguish it from serious journalism or hard news, is a type of media, usually television or online, that provides a combination of information and entertainment. The term may be used disparagingly to devalue infotainment or soft news subjects in favor of more serious hard news subjects. Infotainment-based websites and social media apps gained traction due to their focused publishing of infotainment content, e.g. BuzzFeed.

Penny press newspapers were cheap, tabloid-style newspapers mass-produced in the United States from the 1830s onwards. Mass production of inexpensive newspapers became possible following the shift from hand-crafted to steam-powered printing. Famous for costing one cent while other newspapers cost around six cents, penny press papers were revolutionary in making the news accessible to middle class citizens for a reasonable price.

Advocacy journalism is a genre of journalism that adopts a non-objective viewpoint, usually for some social or political purpose.

Journalistic ethics and standards comprise principles of ethics and good practice applicable to journalists. This subset of media ethics is known as journalism's professional "code of ethics" and the "canons of journalism". The basic codes and canons commonly appear in statements by professional journalism associations and individual print, broadcast, and online news organizations.

Mass communication is the process of imparting and exchanging information through mass media to large population segments. It utilizes various forms of media as technology has made the dissemination of information more efficient. Primary examples of platforms utilized and examined include journalism and advertising. Mass communication, unlike interpersonal communication and organizational communication, focuses on particular resources transmitting information to numerous receivers. The study of mass communication is chiefly concerned with how the content and information that is being mass communicated persuades or affects the behavior, attitude, opinion, or emotion of people receiving the information.

Broadcast journalism is the field of news and journals which are broadcast by electronic methods instead of the older methods, such as printed newspapers and posters. It works on radio, television and the World Wide Web. Such media disperse pictures, visual text and sounds.

Tabloid television, also known as teletabloid, is a form of tabloid journalism. Tabloid television news broadcasting usually incorporate flashy graphics and sensationalized stories. Often, there is a heavy emphasis on crime and celebrity news.

Claims of media bias generally focus on the idea of media outlets reporting news in a way that seems partisan. Other claims argue that outlets sometimes sacrifice objectivity in pursuit of growth or profits.

Media Relations involves working with media for the purpose of informing the public of an organization's mission, policies and practices in a positive, consistent and credible manner. It can also entail developing symbiotic relationships with media outlets, journalists, bloggers, and influencers to garner publicity for an organization. Typically, this means coordinating directly with the people responsible for producing the news and features in the mass media. The goal of media relations is to maximize positive coverage in the mass media without paying for it directly through advertising.

State media are typically understood as media outlets that are owned, operated, or significantly influenced by the government. They are distinguished from public service media, which are designed to serve the public interest, operate independently of government control, and are financed through a combination of public funding, licensing fees, and sometimes advertising. The crucial difference lies in the level of independence from government influence and the commitment to serving a broad public interest rather than the interests of a specific political party or government agenda.

The term "journalism genres" refers to various journalism styles, fields or separate genres, in writing accounts of events.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to journalism:

Nota roja is a journalism genre popular in Mexico. While similar to more general sensationalist or yellow journalism, the nota roja focuses almost exclusively on stories related to physical violence related to crime, accidents and natural disasters. The origin of the name is most likely related to the Mexican Inquisition, where a red stamp was placed on orders for execution or other punishments. By the 19th century, the term came to be used for violent crime, especially murder. With the development of the newspaper industry in that century, news of this type developed long, very detailed stories, which might have a graphic image to artistically depict the event. Both were meant to provoke emotion and sensationalism. The need to provoke emotion in the stories continued into the 20th century, but the introduction of photography in journalism changed both the illustration and text of the stories, with photographs, especially gory ones, dominating nota roja pages and text diminishing to bare facts and violent words. Today, entire newspapers are devoted to nota roja stories and have infiltrated television as well. The genre has also influenced writing and cinema in Mexico as well as prompted criticisms that it promotes and commercializes violence.