Related Research Articles

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains respect for personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and direct democracy among other horizontal networks for the allocation of production and consumption based on the guiding principle "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". Some forms of anarcho-communism, such as insurrectionary anarchism, are strongly influenced by egoism and radical individualism, believing anarcho-communism to be the best social system for realizing individual freedom. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society.

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populism, as shown by its emphasis on equal natural rights, and their practice of reaching the public through pamphlets, petitions and vocal appeals to the crowd.

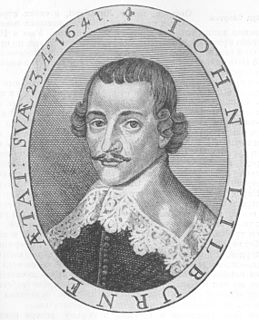

John Lilburne, also known as Freeborn John, was an English political Leveller before, during and after the English Civil Wars 1642–1650. He coined the term "freeborn rights", defining them as rights with which every human being is born, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or human law. In his early life he was a Puritan, though towards the end of his life he became a Quaker. His works have been cited in opinions by the United States Supreme Court.

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from the Levellers, and later became known as Diggers because of their attempts to farm on common land.

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answerable—the authority of God as embodied in the teachings of Jesus. It therefore rejects the idea that human governments have ultimate authority over human societies. Christian anarchists denounce the state, believing it is violent, deceitful and, when glorified, idolatrous.

Gerrard Winstanley was an English Protestant religious reformer, political philosopher, and activist during the period of the Commonwealth of England. Winstanley was the leader and one of the founders of the English group known as the True Levellers or Diggers. The group occupied formerly common land that had been privatised by enclosures and dug them over, pulling down hedges and filling in ditches, to plant crops. True Levellers was the name they used to describe themselves, whereas the term Diggers was coined by contemporaries.

Christian communism is a theological view that the teachings of Jesus Christ compel Christians to support religious communism as the ideal social system. Although there is no universal agreement on the exact dates when communistic ideas and practices in Christianity began, many Christian communists claim that evidence from the Bible suggests that the first Christians, including the apostles, established their own small communist society in the years following Jesus' death and resurrection. As such, many advocates of Christian communism argue that it was taught by Jesus and practiced by the apostles themselves. Some historians confirm its existence.

Anarchism in the United Kingdom initially developed within the religious dissent movement that began after the Protestant Reformation. Anarchism was first seen among the radical republican elements of the English Civil War and following the Stuart Restoration grew within the fringes of radical Whiggery. The Whig politician Edmund Burke was the first to expound anarchist ideas, which developed as a tendency that influenced the political philosophy of William Godwin, who became the first modern proponent of anarchism with the release of his 1793 book Enquiry Concerning Political Justice.

Give-away shops, freeshops, free stores or swap shops are stores where all goods are free. They are similar to charity shops, with mostly second-hand items—only everything is available at no cost. Whether it is a book, a piece of furniture, a garment or a household item, it is all freely given away, although some operate a one-in, one-out–type policy. The free store is a form of constructive direct action that provides a shopping alternative to a monetary framework, allowing people to exchange goods and services outside of a money-based economy.

The history of anarchism is as ambiguous as anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined 19th and 20th century movement while others identify anarchist traits long before first civilisations existed.

English Dissenters or English Separatists were Protestant Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660 which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various forms of republican government.

The right to property, or the right to own property is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely and is typically heavily constrained insofar as property is owned by legal persons and where it is used for production rather than consumption.

William Erbery or Erbury was a Welsh clergyman and radical Independent theologian.

Philip Nye was a leading English Independent theologian and a member of the Westminster Assembly of Divines. He was the key adviser to Oliver Cromwell on matters of religion and regulation of the Church.

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Reformation, a religious and political movement that affected the practice of Christianity in Western and Central Europe.

William Everard was an early leader of the Diggers.

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from Covenant, a biblical term for a bond or agreement with God.

Sidney William "Sid" Rawle was a British campaigner for peace and land rights, free festival organiser, and a former leader of the London squatters movement. Rawle was known to British tabloid journalists as 'The King of the Hippies', not a title he ever claimed for himself, but one that he did eventually co-opt for his unpublished autobiography.

Prior to the rise of anarchism as an anti-authoritarian political philosophy in the 19th century, both individuals and groups expressed some principles of anarchism in their lives and writings.

References

- ↑ Marshall 1993, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Marshall 1993, pp. 97–99.

- 1 2 Gurney 2007, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, p. 214.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, p. 216.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, pp. 215–216.

- 1 2 Gurney 2007, p. 213.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, pp. 215–216; Marshall 1993, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, p. 212.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, pp. 212–213; Marshall 1993, p. 101.

- 1 2 Gurney 2007, p. 213; Marshall 1993, p. 101.

- ↑ Marshall 1993, p. 100.

- ↑ Marshall 1993, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 3 Marshall 1993, p. 101.

- ↑ Gurney 2007, pp. 214–215.