The Holy See, also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome, which has ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the worldwide Catholic Church and sovereignty over the city-state known as the Vatican City.

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period, was the ruler and head of state of the Holy Roman Empire. The title was held in conjunction with the title of king of Italy from the 8th to the 16th century, and, almost without interruption, with the title of king of Germany throughout the 12th to 18th centuries.

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Apennine Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 until 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the Unification of Italy, between 1859 and 1870.

The Holy See exercised political and secular influence, as distinguished from its spiritual and pastoral activity, while the pope ruled the Papal States in central Italy.

In ancient Rome, imperium was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from auctoritas and potestas, different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic and Empire. One's imperium could be over a specific military unit, or it could be over a province or territory. Individuals given such power were referred to as curule magistrates or promagistrates. These included the curule aedile, the praetor, the consul, the magister equitum, and the dictator. In a general sense, imperium was the scope of someone's power, and could include anything, such as public office, commerce, political influence, or wealth.

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monasteries and the pope himself. A series of popes in the 11th and 12th centuries undercut the power of the Holy Roman Emperor and other European monarchies, and the controversy led to nearly 50 years of conflict.

Translatio imperii is a historiographical concept that was prominent in the Middle Ages, but originated from older concepts. History is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an imperium that invests supreme power in a singular ruler, an "emperor". The concept is closely linked to translatio studii. Both terms are thought to have their origins in the second chapter of the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible.

The continuation, succession, and revival of the Roman Empire is a running theme of the history of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. It reflects the lasting memories of power and prestige associated with the Roman Empire.

The history of Italy in the Middle Ages can be roughly defined as the time between the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance. Late Antiquity in Italy lingered on into the 7th century under the Ostrogothic Kingdom and the Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty, the Byzantine Papacy until the mid 8th century. The "Middle Ages" proper begin as the Byzantine Empire was weakening under the pressure of the Muslim conquests, and most of the Exarchate of Ravenna finally fell under Lombard rule in 751. From this period, former states that were part of the Exarchate and were not conquered by the Lombard Kingdom, such as the Duchy of Naples, became de facto independent states, having less and less interference from the Eastern Roman Empire.

Mercurino Arborio, marchese di Gattinara, was an Italian statesman and jurist best known as the chancellor of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He was made cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church for San Giovanni a Porta Latina in 1529.

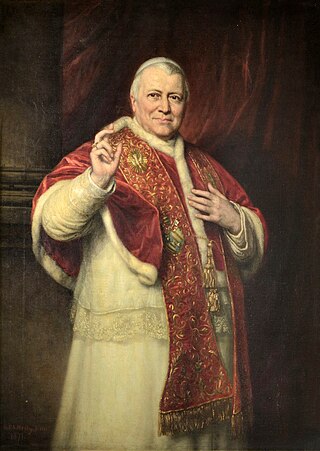

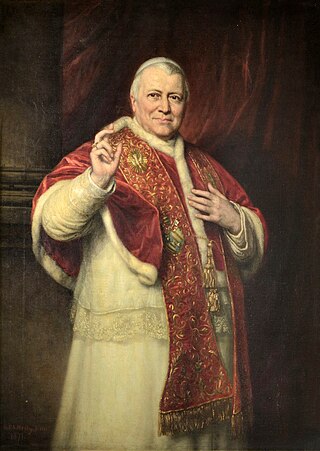

The papal conclave that followed the death of Pius VI on 29 August 1799 lasted from 30 November 1799 to 14 March 1800 and led to the selection of Cardinal Barnaba Chiaramonti, who took the name Pius VII. This conclave was held in Venice and was the last to take place outside Rome. This period was marked by uncertainty for the papacy and the Roman Catholic Church following the invasion of the Papal States and abduction of Pius VI under the French Directory.

According to Roman Catholicism, the history of the papacy, the office held by the pope as head of the Catholic Church, spans from the time of Peter to the present day.

The Kingdom of Italy, also called Imperial Italy, was one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, along with the kingdoms of Germany, Bohemia, and Burgundy. It originally comprised large parts of northern and central Italy. Its original capital was Pavia until the 11th century.

The patronato system in Spain was the expression of royal patronage controlling major appointments of Church officials and the management of Church revenues, under terms of concordats with the Holy See. The resulting structure of royal power and ecclesiastical privileges, was formative in the Spanish colonial empire. It resulted in a characteristic constant intermingling of trade, politics, and religion. The papacy granted the power of patronage to the monarchs of Spain and Portugal to appoint clerics because the monarchs "were willing to subsidize missionary activities in newly conquered and discovered territories."

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

Italy–Spain relations are the interstate relations between Italy and Spain. Both countries established diplomatic relations some time after the unification of Italy in 1860.

The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire occurred de facto on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, abdicated his title and released all Imperial states and officials from their oaths and obligations to the empire. Since the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire had been recognized by Western Europeans as the legitimate continuation of the ancient Roman Empire due to its emperors having been proclaimed as Roman emperors by the papacy. Through this Roman legacy, the Holy Roman Emperors claimed to be universal monarchs whose jurisdiction extended beyond their empire's formal borders to all of Christian Europe and beyond. The decline of the Holy Roman Empire was a long and drawn-out process lasting centuries. The formation of the first modern sovereign territorial states in the 16th and 17th centuries, which brought with it the idea that jurisdiction corresponded to actual territory governed, threatened the universal nature of the Holy Roman Empire.

The papal nobility are the aristocracy of the Holy See, composed of persons holding titles bestowed by the Pope. From the Middle Ages into the nineteenth century, the papacy held direct temporal power in the Papal States, and many titles of papal nobility were derived from fiefs with territorial privileges attached. During this time, the Pope also bestowed ancient civic titles such as patrician. Today, the Pope still exercises authority to grant titles with territorial designations, although these are purely nominal and the privileges enjoyed by the holders pertain to styles of address and heraldry. Additionally, the Pope grants personal and familial titles that carry no territorial designation. Their titles being merely honorific, the modern papal nobility includes descendants of ancient Roman families as well as notable Catholics from many countries. All pontifical noble titles are within the personal gift of the pontiff, and are not recorded in the Official Acts of the Holy See.

In the Middle Ages, hierocracy or papalism was a current of Latin legal and political thought that argued that the pope held supreme authority over not just spiritual, but also temporal affairs. In its full, late medieval form, hierocratic theory posited that since Christ was lord of the universe and both king and priest, and the pope was his earthly vicar, the pope must also possess both spiritual and temporal authority over everybody in the world. Papalist writers at the turn of the 14th century such as Augustinus Triumphus and Giles of Rome depicted secular government as a product of human sinfulness that originated, by necessity, in tyrannical usurpation, and could be redeemed only by submission to the superior spiritual sovereignty of the pope. At the head of the Catholic Church, responsible to no other jurisdiction except God, the pope, they argued, was the monarch of a universal kingdom whose power extended to Christians and non-Christians alike.

From the time of Constantine I's conversion to Christianity in the 4th century, the question of the relationship between temporal and spiritual power was constant, causing a clash between the Church and the Empire. The disappearance of imperial power initially enabled the pope to assert his independence. However, from 962 onwards, the Holy Roman Emperor took control of the papal election and appointed the bishops of the Empire himself, affirming the pre-eminence of his power over that of the Church. However, such was the stranglehold of the laity on the clergy that the Church eventually reacted. The Gregorian reform began in the mid-11th century. In 1059, Pope Nicholas II assigned the election of the pope to the college of cardinals. Then, in 1075, Gregory VII affirmed in the dictatus papae, stating that he alone possessed universal power, superior to that of the rulers, and withdrew the appointment of bishops from them. This marked the start of a conflict between the Papacy and the Emperor, which historians have dubbed the "Investiture Dispute". The most famous episode was Henry IV's excommunication and his penance at Canossa to obtain papal pardon. At the end of this conflict, the Pope succeeded in freeing himself from imperial guardianship. In 1122, under the Concordat of Worms, the Emperor agreed to the free election of bishops, reserving the right to give prelates temporal investiture. This compromise marked the defeat of the Empire.